Rock musicals of the 1970s are one of numerous corners in pop culture that represent the rapid change of taste happening during the New Hollywood era. For decades, the traditional musical was a reliable gimmick for Hollywood. Ever since Al Jolson sang “Mammy” in blackface, musicals became a consistently safe box office investment. For example, MGM, a studio most consider to be the pinnacle of old Hollywood, relied heavily on musicals.

A great example of the traditional musical’s reign is Singin’ in the Rain. It’s now considered by some, including myself, to be their all-time favorite film. But when it was first released, people didn’t recognize the film’s superiority. Less than a month prior to the release of Singin’ in the Rain, Gene Kelly won an Academy Honorary Award for his achievements made while working on An American In Paris, a film that won six Academy Awards. That film’s climactic ballet with a half million budget, use of 44 sets, and 17 minutes of dialogue-free dancing was as successful as a film could be in creating a spectacle nobody could replicate.

Just a few months after An American In Paris exceeded the limits of what a musical was capable of, Singin’ in the Rain was released. As you’d imagine, people still processing what they experienced from An American In Paris were underwhelmed by Singin’ in the Rain. The one Academy Award nomination the film received was Best Supporting Actress for Jean Hagen’s incredible performance as Lina Lamont.

Singin’ In The Rain following An American In Paris in less than half a year’s time hopefully translates how essential and consistent musicals were for Hollywood.

Like everything, the traditional musical experienced a demise. Not long after The Sound of Music surpassed Gone with the Wind as the highest grossing film of all time, the rise of New Hollywood began. After Easy Rider and Bonnie and Clyde became unpredictable box office successes, every reliable playbook Hollywood had became irrelevant. No genre experienced damage from the generation gap like musicals did. While the 1970s housed successes like Grease, Fiddler on the Roof, and Cabaret, those were the rare exceptions compared to a time when hit musicals were consistently pumped out on a conveyor belt.

There are multiple examples of the low point for musicals in the 1970s. The Wiz, while in the hands of a loving audience today, was a box office failure credited for killing Blaxploitation. Michael Jackson’s right, you can’t win.

The most amusing example is 1974’s Mame. Based on a hit Broadway musical that starred Angela Lansbury in an adaptation of the classic Auntie Mame with Rosalind Russell, the film version Mame stars Lucille Ball because Warner Brothers felt Angela Lansbury lacked star power. Lucille Ball was a questionable choice because, for all her talents, she can’t sing. Her voice is like a drag queen impersonating Kathleen Turner’s throat molded by years of cigarettes.

With this void left from the absence of the traditional musical, rock-influenced musicals began to rise to the surface.

Rock musicals had existed prior to what could arguably be considered their golden age. What’s considered the first rock musical, The Girl Can’t Help It, was released in 1956. With its skilled use of Jayne Mansfield and rock icons like Little Richard and Eddie Cochran, it’s still one of the most stimulating experiences put on screen. Since I routinely share the interests of your deceased grandfather who haunts the house and wails in the attic at 3am every night, Julie London’s scene is where the film really injects itself into my veins.

There’s also The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night. Because of the devotion that band still attracts today, I imagine it’s the only black and white film some have ever sat through.

But the obvious film to point towards when beginning a discussion of 1970s rock musicals is, of course, The Rocky Horror Picture Show. With a bland series like Glee doing a Rocky Horror themed episode and every abandoned factory building housing a Rocky Horror production, it’s hard to find a more exhausted title. At the time of its release, the film was a generation’s education in the power of a cult classic. When originally released, Rocky Horror played to empty seats. Then someone got the bright idea to screen it at midnight and the film found its crowd.

Rocky Horror has its strengths and faults. With a bisexual transvestite as a lead character, Rocky Horror was one of the first films where LGBT representation was front and center. Prior to that, you had to watch Peter Lorre presenting a Gardenia-scented calling card or focus on the way his lips wrapped around the end of his cane in The Maltese Falcon to find any representation in a mainstream Hollywood film.

The greatest fault of Rocky Horror is how it influenced the most boring people to scream at a screen. Nothing’s more exhausting than loud obnoxious assholes who think they’re witty. The rarest thing you could find is someone with a great sense of humor thinking, “I’ve gotta let these strangers know I’m hilarious by screaming for two hours.” I imagine Hell is a never-ending screening of Rocky Horror with nuisances shouting “WHY DON’T YOU BUY AN UMBRELLA YOU CHEAP BITCH” at Susan Sarandon.

For this piece I wanted to pass over Rocky Horror because its story has been told, and any punk attitude that film had has been lost over time. In order to translate the weird aura that film once had, I’d have to interview someone who was there, a person who can vividly recall the betrayal and heartache experienced when KISS released their disco album, Dynasty. Instead I’ll be talking about rock musicals that aren’t abused every October. I’m also more interested in putting a spotlight on these two films because unlike Rocky Horror, both of these insane rebellious adventures are rated PG. There’s something so punk about being a Trojan horse, and that’s what these films are. During their theatrical releases, children could buy a ticket without a parent. And who knows how many children years later gave the VHS box to a guardian at a rental store and showed them how the film was, in the eyes of the MPAA, something appropriate for young impressionable audiences.

The first film in this double feature, Phantom of the Paradise, slowly found its audience over time. The first time I ever heard of it was on The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast. On multiple episodes, Ellis has mentioned how he went to the theater and saw this film at the age of ten. Since this is an experience he still recalls and cherishes, it wouldn’t be crazy to say this film’s thrilling experience played a part in molding the mind that gave us great dark novels like Less Than Zero and American Psycho.

Like many great things, Phantom of the Paradise is something where you can use the classic line, “You couldn’t get that made today.” It was distributed by 20th Century Fox at a time when that studio, like many corners in the entertainment industry, realized they could no longer predict what worked, so they relied on creators to connect with a generation. An example of this creative freedom outside Phantom of the Paradise is Beyond The Valley of the Dolls, a film that, among many wonderful bizarre moments, has someone being decapitated and their severed head rolling across the floor as the 20th Century Fox theme plays.

Few films document how much the MPAA has changed over the years better than Phantom of the Paradise. While the MPAA is now eager to censor films, the MPAA of the ’70s was carefree. Phantom of the Paradise showcases the once chill authority figure that the MPAA was because no PG film features more drug use than this one.

The first group highlighted in the film, The JuicyFruits, smoke a jumbo-sized joint on stage. Nowadays the barely noticeable presence of pot guarantees an R rating. Soon after that, the film dives into documenting the darker side of the entertainment industry by showing how carefree everybody is with pills. Whenever a performer doesn’t feel right about what’s going on at The Paradise, Philbin quickly shoves a pill into their mouth to shut them up. Our Phil Spector stand-in, Swan supplies Winslow with pills in his dungeon studio. At one point he presents him with a Hunter S. Thompson suitcase and refers to it as breakfast. The final sheet of music Swan pulls from under an unconscious Winslow is covered in pills.

While pointing out the examples of the way Phantom of the Paradise documents the dark side of entertainment, there’s even a casting couch scene with women on a bed fooling around to impress Swan, watching from one of his many security cameras.

Along with the drug use, there’s a great supply of violence. Our main character is mutilated after falling headfirst in a record press and can be seen running away with his outfit covered in blood while gargling in pain. You also have Beef, an iconic character from his very brief time on screen, being electrocuted and his corpse burning on stage before a thrilled audience. You later see that same audience chanting his name while the charred corpse is put in an ambulance.

The chaotic finale of this film really makes you wonder how it got a PG rating. At one point Paul Williams is hissing without any skin on his face while George Memmoli’s corpse is on the ground with blood pouring from a head shot. This is the moment where you see the film pushing 10-year old Bret Easton Ellis down a dark path that eventually brought him to American Psycho, where the most graphic murders blend with detailed music critiques.

With how dull and bloated films have gotten since, Phantom of the Paradise ages well. Even with rough edges, you have to admire a young Brian De Palma eagerly stockpiling references to Phantom of the Opera, Faust, The Picture of Dorian Grey, and Frankenstein into a 92-minute runtime. It also doesn’t hurt the film’s soundtrack is supplied by Paul Williams, an iconic singer and songwriter who’s done it all from writing songs for Karen Carpenter and Kermit the Frog to having a cocaine addiction only rivaled by the 1986 New York Mets.

The second half of this double feature, Tommy, found its audience more quickly than Phantom of the Paradise. It grossed over $34 million against a $3-5 million budget. Those numbers seem meager now, but in 1975 that was enough to be a top earner.

Like Phantom, Tommy is a fascinating time capsule of the New Hollywood era. One of 1975’s blockbuster releases was a musical based on a concept album following the journey of a deaf, dumb, and blind child becoming a pinball prodigy and a spiritual guru. All the dialogue is spoken through song similar to Jesus Christ Superstar. It’s safe to say this experiment now wouldn’t be the profitable investment it was then.

Similar to Bret Easton Ellis discovering Phantom of the Paradise at the age of ten, Tommy was something I found at a young age. Walking past the musicals section in a local rental store, I saw a VHS box with a guy with sunglasses and a cork in his mouth. I picked it up, turned it over, and was immediately frightened by the image of a crazed Tina Turner on the back holding up an Acme-sized syringe. Children who wandered around video stores always have a couple of images that almost made them abandon their potty training. This was mine.

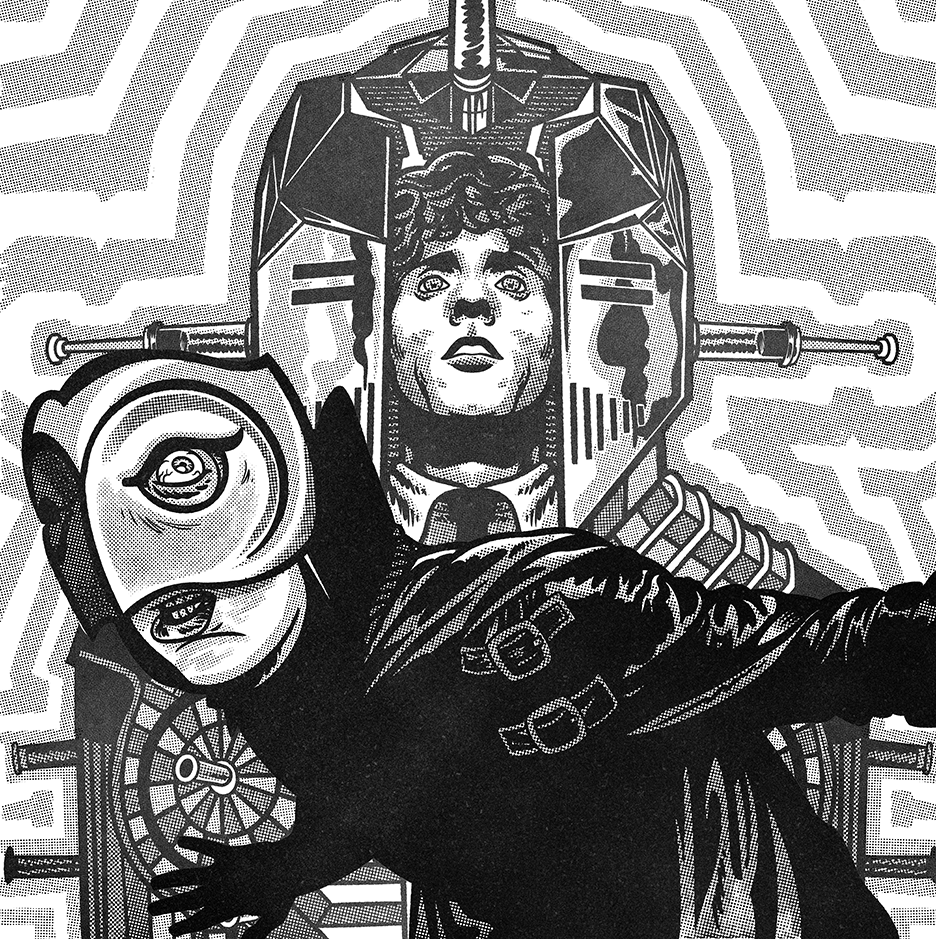

In middle school I finally watched Tommy, and it immediately became an obsession. This film more than any might be why I rarely feel compelled to see something I haven’t already gotten around to. Tommy’s visual creativity takes you back to when there was at least the illusion of unexplored territory for filmmakers to discover. There’s one moment in Tommy that immediately goes from Eric Clapton performing for a church that bows at the feet of a giant Marilyn Monroe statue to a charismatic Tina Turner morphing into a giant Metropolis robot that Roger Daltrey climbs into and gets injected with at least 20 syringes.

Because of Tommy I already feel like I’ve seen everything a film can do.

Arguably the most stimulating visual might be Ann-Margret rolling around in a mixture of detergent suds, beans, and chocolate. For any viewers with a sploshing fetish, it doesn’t get more arousing than seeing the eye candy from Viva Las Vegas lost in this hysterical, orgasmic haze.

My favorite scene has always been Paul Nicholas’ energetic “Cousin Kevin” number. I used to send 15 second snippets of this to everyone I knew in the mid-2000s when cell phone videos were pixelated jumbles. Imagine having no knowledge of this film and attempting to make out blurry clips of a guy in a leather jacket drowning someone and kicking them down a staircase.

As long as I’m babbling about personal ties to this film, I should mention this is the first film to introduce me to Oliver Reed, a performer I’m obsessed with. From the moment I saw him, I was immediately compelled by his presence. Nobody is more of a man’s man than Oliver Reed. Whether it was acting, entertaining on a talk show, or destroying his liver, Oliver Reed succeeded at everything he attempted.

Oliver Reed was good friends with Keith Moon, which really makes me wonder what horrors they must’ve caused in pubs across Europe. Oliver Reed was the poster boy for alcoholism, and Keith Moon was mayhem incarnate — even before using drugs and BDSM to escape the trauma of running over his friend with a limousine and dragging him across several blocks towards the most painful death ever known. One of many urban legends about Keith Moon’s debauchery has him leaving a hotel and suddenly saying to the driver “stop, I almost forgot something.” He went up to his room, tossed the television into the swimming pool, and came back in the car saying “I almost forgot.”

Along with surreal imagery, Tommy throws you back to that time of the ’60s and ’70s when thought-provoking entertainment was trendy. It was a time when even bubblegum acts like Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons released a concept album titled The Genuine Imitation Life Gazette, an album where the first song from the group who gave you “Big Girls Don’t Cry” and “Walk Like A Man” is “American Crucifixion Resurrection.”

Within a PG film, there’s a Christmas song exploring the idea of a deaf, dumb, and blind child having no awareness of Jesus Christ and how this will result in his soul not being saved. If you wanted the complete opposite of caroling with The Carpenters and Perry Como, it’s right here. That scene happens soon after a child watches his new stepdad kill his father who was presumed to have died in the war, which the terrible shock of makes him deaf, dumb and blind. Once he grows up into Roger Daltrey, he’s molested by Keith Moon…in a PG movie.

This might be an ideal time to say this recommendation is directed towards any parents reading this article. If repeat viewings of Willy Wonka and The Chocolate Factory isn’t causing your child to be warped by the image of a millipede crawling over a woman’s mouth, Tommy will do the trick. Research shows trauma brings out the best in a child. Perhaps they’ll be at the top of their class, maybe they’ll blow you away with a shotgun like The Menendez Brothers. Risks must be made to mold a future generation!

Now comes the time where I say I’m so glad we had this time together and tug on my earlobe. If you’re looking for a double feature guaranteed to pull you from whatever dust-coated stupor you’ve fallen into, few things are as reliable of a cure as these two films. They perfectly sum up a time when mainstream Hollywood was taking a chance on things they didn’t understand because audiences were more fascinated than ever by films that strayed far from tradition. Both films also document a rare moment when the MPAA took a break from the belief that they were in charge of upholding the morality of every viewer.