Amateur street racers fire grappling hooks into the sky, take down a military cargo plane, and save the world. A zoologist whispers kindly to a kaiju-sized ape, surrounded by the complete destruction of a city, and turns a monster into humanity’s most valuable friend. Lost in the chaos of the waves, facing an ancient dinosaur shark that could swallow Moby Dick whole, a deep sea diver slays the beast single-handedly with a spear. A meteorologist shatters the glass ceiling of a mall, exposing himself to the largest hurricane mankind has ever witnessed, to suck terrorists into the sky while holding on to his own life and another’s with nothing more than a rope. These are just a few of the scenes from a new breed of action movie that dominates major studio blockbusters today. None of these heroes have superpowers. To call them Herculean would even be a misnomer, as they are distinctly not the children of gods. They are a callback to the turn of the 20th century, a sort of World’s Fair-style testimony to the indomitable spirit of man. They are the everyman, not only doing the impossible through will alone, but empowered by a certain humanitarian ethic that allows them to overcome cartoonishly absurd circumstances. How did things get here though?

“Blockbuster” became a buzz term in entertainment magazines during the first half of the 20th century, when writers cheekily began describing motion pictures using the same metrics as a bomb dropped by the Allied Forces in WWII. These movies were always big-budget Hollywood productions, exploding into cinemas, and were expected to provide the studios a big return: high-cost films designed for high earnings. Evoking the power of the 2.7 million tons of bombs strategically dropped on enemies and civilians alike by the Allies in WWII may not be the most respectable phrasing possible, but it certainly was patriotic. At this time, “blockbuster” seemed to be thrown around to describe not just an action film but also a variety of genres; as long as the movie seemed like it would be a “hit,” it fit the criteria. This is why Gone With The Wind (1939) and The Ten Commandments (1956) are considered blockbusters of the early eras, while today one might brush off pictures of that sort solely as big production dramas. But, fast-forwarding a few decades, the blockbuster finds a bit of refinement. Varying degrees of big action movies dominate here, with the Reaganism of the 1980s supplying audiences with jingoistic odes to big guns, muscle men, and explosions. This is the era in which blockbusters may have been at their most sophomoric, in which their reputation–especially among deadpan cinephiles– dwindles down to a dismissal of “big dumb fun.” However, cultural and political changes of the 1990s ushered in another shift for the blockbuster movie evolution: seriousness.

If the ‘80s were a time of excess, the ‘90s were a time of crossover. That crossover may seem innocuous at first as the shift from ‘80s-style male-centered burly action to mid-’90s family-friendly rollicks provided audiences with more easily digestible nationalism in films like Independence Day (1996). And not to mention the wholesome action adventure introduced in films like the colossal Jurassic Park series (1993 and on). But the late ‘90s brought almost accidental blockbusters such as The Matrix (1999) that weren’t necessarily huge hits at the box office, yet resonated with audiences so profoundly they changed culture forever. The appeal of The Matrix especially was that it endeavored to combine its action with a more or less clumsy philosophy lecture, and honestly, it blew people’s minds. Could an action movie be…smart? It’s noteworthy too that the decade had been ushered in by the sudden popularity of the indie film, in particular with an edginess that was lost in major parts of popular ‘80s filmmaking. Pulp Fiction (1994), Trainspotting (1996), and the Wachowskis’ pre-Matrix entry Bound (1996) all became cultural landmarks for their raw humor and tragic themes. To many, this felt like an anti-blockbuster movement, even if one could argue that films like Batman (1989) had already shown that darkness could work for the masses with big action films. The Matrix dispelled this illusion though, melding chin stroking with ass-kicking seamlessly. Things were changed forever, never to look back, right?

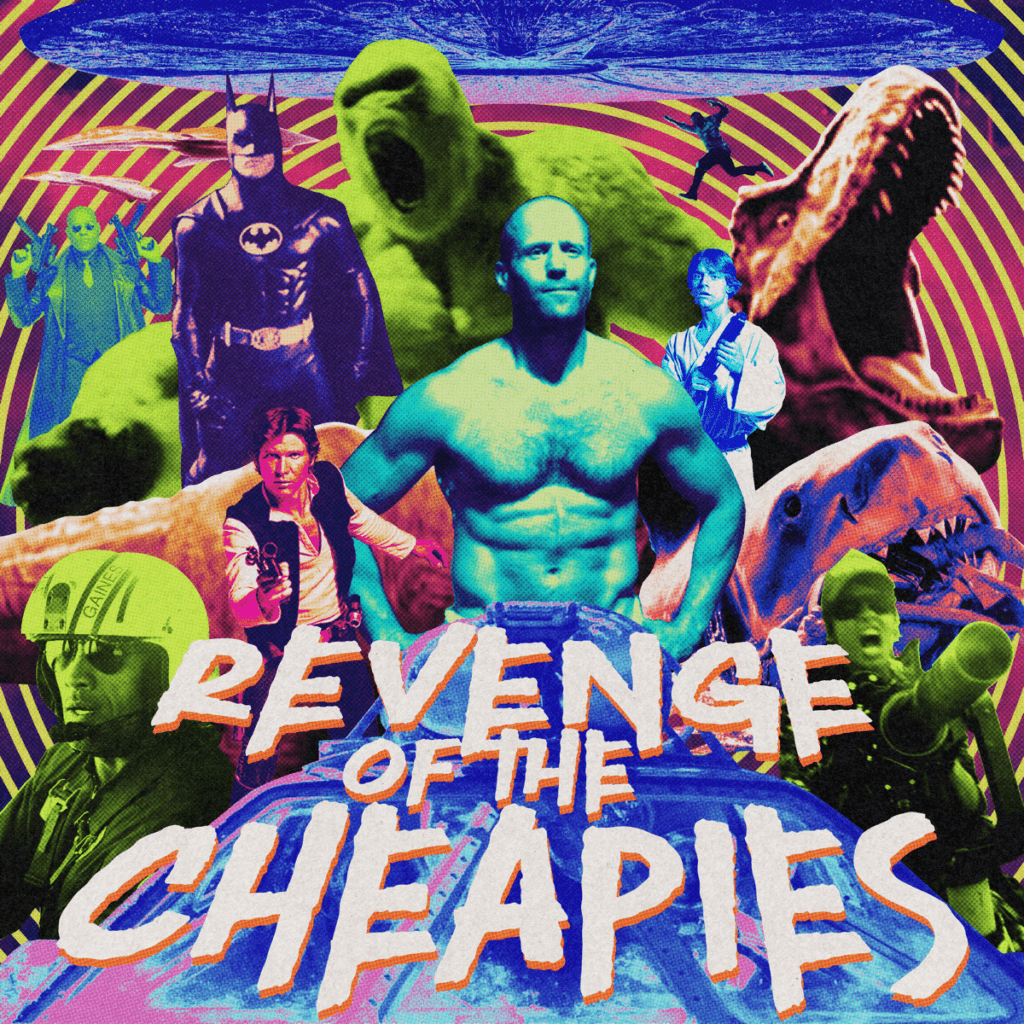

Time to look back actually. All the way to the Poverty Row films of the black-and-white era and up through grindhouses, drive-ins, and video nasties. Often referred to as “cheapies” or “quickies,” the budget-friendly pictures of the early eras of filmmaking are what fans and scholars generally call “B-movies.” These easy-to-make pictures did not stray from their visually identifiable individual genre and often were uncomplicated in such a way that the audience would know what to expect from them. Westerns, comedies, gangster films, film noir, and sci-fi/horror pictures were most closely associated with the early B-movie.

So when modern filmmakers employ visual cues and story beats that match the B-movie custom, but they’re given the budget of a thousand or more preceding B-movies to perfect them with, the result can be extreme. A big-budget B-movie may seem like an oxymoron, but so many Hollywood tentpoles play with this dynamic. Star Wars (1977) took the kitschy Flash Gordon-style space opera and ran it through a ‘70s gritty lens of realism to make it feel classy. The current crop of MCU films uses decades of Disney family-friendly expertise to iron out the wrinkles of wild comic books and present a massive, if not muted, soap opera. Even the exalted Matrix films are rooted in the pulp shelves of sci-fi magazines for nerdy disaffected teens. Arguably, the storytelling tradition of B-movies is everywhere in what people call blockbusters. Big B, though, is something slightly different. Big B refuses to apologize for the low-brow elements. It is also distinctly a moment in time that could not exist before all the cultural moments leading up to 2010. There are signatures to Big B that are common, but not necessarily required. The Everyman. Bloated CGI. Narratives that spew out absurdity. These are all unmistakable tell-tale signs of the Big B, but what really matters is that combination of classic blockbuster and disposable B-movie. That is what makes these films notable: creativity and innovation blended with successful execution of technique and technology all due to having less of a budgetary restraint. It is a rollercoaster term, but the ramp to the first drop was a long one.

By 2000, an ’80s-style action blockbuster was considered laughable by many. Even the Wachowskis had difficulty taking steps away from the perceived dead seriousness of their 1999 blockbuster, with fans saying that the cave rave scene of The Matrix Reloaded (2003) didn’t fit with the tone of the first film. Years later, when they would present the world with the hyperactive and hyper-colored Speed Racer (2008), it would be considered a massive flop until embraced by a cult following well into the 2010s era of Big B.

Somehow though, a 2001 film would end up being the little engine that could, birthing the flagship franchise for an entirely new era in action blockbusters. The Fast and the Furious lacks many of the signatures of Big B. It is not nearly as absurd as the films it would inspire a decade later. The protagonists are less half-veiled socialist heroes as they are simply anti-heroes. Yet, at the core, there are many traits that remain unshakable to an entire movement in cinema. Most importantly, The Fast and the Furious embraced an ‘80s-style light-heartedness even when characters were defined by tragedy. It also laid the groundwork for the everyman hero, not just because these were mortals, but in its distinctly anti-police stance. The climax of the film hinges upon LAPD officer Brian O’Conner learning to choose his new family over the institution of law. This theme remains at the heart of the franchise, re-emerging most significantly in Fast Five (2011) when antagonist Luke Hobbs disregards his role as a DSS agent and helps the family of heroes steal a massive safe from a corrupt police station, destroying much of Rio in the process.

These first five Fast and Furious films represent a growing arc toward the absurdism that would come to define the true Big B. The third entry The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006) and the fourth Fast and Furious (2009) lean heavily into grim, even nihilistic themes that still echo the serious approach of ‘70s and ‘90s filmmaking. One of the most important set pieces in Tokyo Drift is jaw-dropping for its philosophical absurdity more than anything cartoonish, with the protagonists choosing to drift through a crowded major intersection putting hundreds of lives at risk, lives that belong to those who, just a few scenes earlier, one of the anti-heroes of the film had looked upon from a rooftop and called “lemmings.” The 2009 entry into the franchise has one of the few tragic endings in the series, with the family head Dominic Toretto being sent to prison. The post-credits scene presents an exciting ray of hope though, revealing that Brian O’Conner has now fully committed to this family of outlaws and is among those who will use street racing cars to break Dom out of shackles. This energy does ultimately spill over into Fast Five, defining it more than anything else, but even then it is not a full-blown Big B. It teeters the line but plays so well at being an expertly crafted heist movie, the sort Walter Hill could have written, that the cartoon elements still feel earned in a magical realism sense. Even the first act of the movie focuses on how hard the lives of these outlaws are, living as fugitives unable to support their families. By the end though, outlaws have become vigilantes–and extremely rich ones at that. From this point on, the Fast and Furious franchise would be more concerned with ridiculous odds and joyously saying “Family!” as many times as possible to remind the audience that love and humanity (and maybe God) are all far more important than the laws of both government and nature. Philosophy remains in the franchise but is far removed from the faux academy of The Matrix-style films. In a “blink and you miss it” scene in Fast Five, the ridiculously successful mob boss of Brazil who controls both the favelas and the cops, explains that his approach is not to rule by fear, but rather is modeled after the American capitalist method of giving people exactly what they need so they come to rely upon him. The Fast franchise’s philosophical teachings don’t come across as university lectures. They embrace the true pop spirit of pure entertainment: as truly American as the term “blockbuster” while questioning the American status quo itself.

In his book Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste (2014), Carl Wilson makes a compelling argument that people’s sense of class placement is the primary factor in a culture’s sense of art being low-brow, middle-brow, or high-brow. For instance, the history of heavy metal, in general, goes from being embraced by a blue-collar, rural, working class in the late ’70s and ’80s, making it seem like a low-brow art form at first. By the end of the ’80s, the same bands were embraced by MTV and pumped into every suburban home, thus becoming a middle-brow form of entertainment. Then, after falling from grace during the grunge years of the ’90s, these same albums were rediscovered by hipster art kids in the 2000s, transcending to high-brow status (even if “ironically”). The B-movie, particularly through the same decades, has a similar history. When relegated to seedy urban grindhouses and dusty drive-ins, these films were the low-brow runts of cinema. As the need for suburban Mom & Pop video stores to stock more and more films in the ’80s grew, the same movies and those similar transformed into middle-brow by becoming household staples for suburban teens looking for late-night popcorn thrills. Most recently, thanks to reissues via boutique Blu-Ray companies in the 2010s and networks like Shudder once again turning Joe Bob Briggs into the face of “speaking intelligently about trash,” the same exact films have risen to the height of pure art.

Big B does something fairly sophisticated in relation to this theory of cultural appreciation though. These are not old movies rediscovered and recontextualized, they are brand new. Benefiting from both major studio budgets and B-movie sensibilities, the gap between low-brow and middle-brow is instantly collapsed into something new. Oftentimes pulling in directorial talent like James Wan, one could argue there is even sometimes a “Steven Speilberg elevating the animal attacks subgenre into Jaws (1975)” sort of high-brow element involved. This isn’t to say that public opinion on these films isn’t wildly varied, but that only makes this case even stronger. What are Big B films in relationship to class sensibility? They blur and confuse these lines in a manner that only entertainment made with the hindsight of over a century of filmmaking could.

By the 2010s, a canon of Big B emerges. The Fast franchise enters into its second half from Fast and Furious 6 (2013) forward, switching gears to wild, over-the-top spy action, rather than outlaw heists. The climaxes of these entries find the beloved family of car friends taking down Godzilla-style monsters in the form of giant military planes and arctic nuclear submarines. For the films, the budgets couldn’t be bigger. The craft couldn’t be more state-of-the-art. And the narratives couldn’t be more lovably stupid. Even when dealing with serious affairs, like how to reconcile Paul Walker’s tragic death with the ongoing series, these films lean in on an epic soap opera style, not unlike the first films called blockbusters. Big B outside of the Fast franchise often has slightly more humble aspirations. Battleship (2012) and San Andreas (2015) both have all the core feel of Big B but lean heavily into themes quite the opposite of Fast’s folk hero roots. Ray Gaines, a helicopter rescue fireman remains cool and collected in the face of the worst catastrophes Mother Nature can throw at humanity in San Andreas. It doesn’t matter if he is a symbol of the ultimate inner strength of mankind or just stupidly arrogant, the message is distinctly middle-brow: “just doing [his] job, ma’am.” San Andreas can, through a cynical lens, be seen as another Big B with family as the core value. Although in that case, it would be the earthquake that is the real hero here, as it is the clear factor reuniting the protagonist played by The Rock with his loved ones. Battleship is even far more direct, and its blockbuster style brashly knucklehead patriotic: Military is good, shoot first ask questions never. It is as much a spectacle as one would hope for in this golden era of Big B, and really understands the mission statement by resolving everything in a boxing match with an alien. The folk hero origin of Big B is embraced once again by the director of the first Fast film, Rob Cohen, in Hurricane Heist (2018) in a simultaneous battle against Mother Nature and outlaws in the middle of a US Treasury heist. The police are revealed to be corrupt and the heroes are a meteorologist and his alcoholic brother. In the end, it is implied that not only do they decide to keep the money for themselves but they also convince the one patriotic Treasury agent to go rogue and do the same. Cohen shows here that not only did he inadvertently invent Big B, but that he remains the true master of it. It is worth noting that his film Stealth (2005) is wildly ahead of its time in terms of this film movement. The Rock, on the heels of the success of San Andreas, returned to literally being one man versus a skyscraper in Skyscraper (2018). This time around, the protagonist moves from Fireman to FBI though, ever digging The Rock deeper into his middle-brow over low-brow approach to the subgenre. Even in the Disney-bankrolled Rampage (2018), The Rock’s zoologist character is ex-military. That said, this may be The Rock’s sweetest and most tender role, a characteristic he often uses to balance with his tough guy exterior and maintain his early WWE “The People’s Champ” persona.

None of these films have led to a sequel, though, except another kaiju-themed entry, The Meg (2018). Based on a book that easily can be considered a post-Jurassic Park cash-in from 1997, time and distance makes the film adaptation truly its own thing rather than a mockbuster. Pulling in indie auteur Ben Wheatley to direct on the upcoming sequel Meg 2: The Trench (2023) is a sign that as Big B enters into a new decade, the high-brow element may become even more pronounced as the subgenre continues. This new decade even began with F9 (2021) serving as a sort of self-aware satire of the franchise that built a movement. Not only did this film finally give fans the half-joking request to send race cars into space, but includes an existential crisis from Roman Pearce when he realizes their team essentially never gets hurt, as he wonders if they are actually gods. Again though, the Fast franchise proves itself to be the most philosophical Big B of all when Dominic Torreto is asked, while in prison, if life is real or an illusion. His response: “It doesn’t matter. It’s all about how you choose to see it.”

Massive, reactionary cultural shifts feel almost dead in America since the new century began. From the rock ‘n roll ‘50s to the psychedelic ‘60s and dusty porn revolution of the ‘70s to the slick, electronic ‘80s and into the dark, protest-fueled ‘90s of grunge, gangsta rap, and cyberpunk, everything since 9/11 and the dominance of the internet and social media has leveled the cultural playing field. Simultaneously there is space for pockets of everything to be found by anyone, and the corporate stranglehold on mass media is stronger than ever. As a result, there haven’t been many (or any?) moments where a Nirvana or Tarantino suddenly changes the entire conversation. The Fast and Furious films, which took five entries and an entire decade to emerge as a defining voice in current pop culture, are as much ahead of their time as they are molded by it. A slowly evolving force that chicken & egged along with the winding river that is contemporary entertainment. These films, and many others in the Big B canon, all incorporate artistic elements developed through the second half of the 1900s. Given that pop culture itself is a byproduct of the bombs dropped in WWII, a luxury of the creation of suburbs, and the end of teens being sent to factories to work, it makes sense that the frantic growing pains of art and culture becoming corporate entertainment would eventually level off. Pop culture was new. Now it is less so. The Big B films are as sprawling and epic as Lawrence of Arabia (1962). They’re as thrilling yet as safely streamlined as Jaws. The bubblegum and muscles of the ‘80s have returned, but along with it, the interweavings of drama and philosophy that the ‘90s claimed would usurp it all. Yet, despite being the masterful students of such great teachers, they hold onto the absurdity of the classic B-movie. From ‘50s giant monsters to ‘70s disasters and animals attacking, to the direct-to-video-loving stupidity of the ‘80s, Big B gives these crowd-pleasing narratives a place at the head of the table. One may take away from these films whatever they wish. Perhaps they are as smart as Bruce Springsteen’s protest-in-the-guise-of-patriotism song, “Born in the U.S.A.” Or maybe they’re disgusting perversions like naming a sexy article of clothing “the bikini” after atomic bomb testing. More likely than anything though, they are both of these things and everything in between, like a COEXIST bumper sticker using corporate logos instead of religious iconography. The experience for audiences, though, is, and always will be, deeply personal. Why else would Big B’s true credo be just a single word, “Family”? ★

Further reading on this topic:

Action: The Unspoken Genre

The Visual and Comedic Absurdity of Torque