Although steeped in the traditions and trappings of what could be done in 1943, Stormy Weather was an early effort for mainstream Hollywood to bring blackness to the forefront. As such, the film holds a special place in the legacy of movie musicals, particularly the musicals of its own era. But, it’s more than just a classic musical. The transgressive nature of the film was carried out under the guise of a Hollywood white-safe Trojan horse adorned with the expected racist stereotypes and headlined with top-notch entertainers working under the radar. At the same time, it’s a semi-biopic, historical collage of black entertainment, and talent showcase, and it’s deftly efficient. Despite having the standard reductive trappings, Stormy Weather upstaged the expectations of its time while never missing a step.

Classic Hollywood, as with other early American filmmaking regions, set up the foundation of film as the modern world understands it. An unavoidable common factor in many of these scenes and their storytelling is indeed whiteness; this is demonstrated not merely in terms of showing white actors but also in using white and Western cultures as the default cinematic experience, and only allowing those stories to be shown to the widest audiences. Granted, that was the case for Western storytelling in general. The American black experience was shoved off to the side or used as the butt of the joke. Specifically, I’m referring to a film like Birth of a Nation (1915). This was not only a massive blockbuster but it was the benchmark for how blackness (as well as other non-whites) was allowed to be shown on-screen for mainstream film. With all that said, though, there were black filmmakers and even a full-on independent industry of black films during the early years of American cinema.

These were race films – the black pictures. These were exploitation films. Following the traditional and no-frills definition of exploitation film, race films catered to a specific audience and exploited what they like or want for profit (Lifetime and Hallmark are modern-day exploitation factories, it’s not just Roger Corman). The future Hollywood mega-studios were in their infancy but still had a massive reach and more resources in comparison to the race film studios. The race film industry had several smaller independent studios across the country. There were a few major players: Afro-American Film Company, Peter P. Jones Photoplay Company, Norman Studios, Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Foster Photoplay Company, Ebony Film Company, Colored Players Film Corporation, and Micheaux Films. At this point, the only part of this scene that gets any mention now is Oscar Micheaux with his Micheaux Films. The earliest surviving film is 1920’s Within Our Gates, directed by Micheaux.

The key factor that made these different from what early Hollywood was offering up was authentic blackness. Race films cast a majority or entirely black performers. From 1916 to 1942, race films were left to a smaller system and circuit. Since these were smaller-scale films free from the major studios and had black voices present in the production, they could buck the mainstream trends, i.e. give black characters a basic humanity. Trends in black cinema have morphed over the years, from the under-appreciated ’70s/’80s LA Rebellion movement to ’80s/’90s Hood films to the current Oscar-bait inspirational fare. The original race films were united by the simplicity of showing black life at that point in that time. They weren’t drenched in racial terror, nor were they misguided misery porn or faux-inspirational Oscar pap. These early films covered all the popular genres: dramas, romance, Westerns, musicals, and more. Folks just got to see themselves on the silver screen. The power of which can’t be overstated.

Religion, urban life, music, the entertainment industry, and simple everyday life were the major themes that cropped up during this time. You see humans who are black existing as complete beings in a variety of scenarios. That’s revolutionary when compared to the Hollywood fodder black actors were offered. There could be dignity and subversion in a “massa” role but race films offered so much more. In playing within the pasty white Hollywood studio system, Stormy Weather managed to be progressive by being regressive; they gave the studio what was wanted but with a twist. The big-budget race film experiment was short-lived despite Stormy Weather‘s box office success. It was a top ten film for Fox’s box office. It seemed like people were ready but the system was not, which is usually the case for pushing progress forward.

Black faces and people were already a staple of American entertainment though, but in a different context. Blackface minstrelsy was one of the first uniquely American art forms. It was the American theatre. It was the American pop music. It was the mainstream American entertainment. It was a fundamental part of American culture. Originating in the 1830s, blackface minstrelsy was first established and presented throughout the nation and later on beyond its borders. An important distinction was it was not always in jest; there were layers. Some performers used it for mocking and some used it to honor black culture. Because it was black culture, the appropriation was deemed okay: the culture was disposable and disrespected enough that it was fair game (and this is still relevant). Black faces were used in other parts of the world to portray demons and evil entities, but in the good ‘ole US of A, it was specifically black enslaved people. The first minstrel superstar performer, Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice, was white. He’s considered to be one of the originators of this American art.

The popularity of Thomas Rice’s Jim Crow character inspired a line of others – Daniel Decatur Emmett, Edwin Christy, and George Washington Dixon. According to the story, Jim Crow emerged from seeing a black stagehand dancing a shuffle and singing a song. The man (or song) was named Jim Crow. Rice stole the dance, song, and persona for himself. Traditionally, burnt cork mixed with shoe polish or grease paint was used with wigs, big red lips, and gloves (the gloves that cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse wear were a nod to this). This look would become the face of American entertainment. Early American animation was a variation of minstrelsy but with the overtly racial tones remixed and replaced, however, the influences are so ingrained that some of them are borderline invisible. The blackface minstrel entity is an essential part of American history and culture, for better and worse. It was an inescapable force that only got more popular post-American Civil War. Blackface minstrelsy transformed one heinous form of slavery into another kind of cultural slavery. By this point, it was a method for slyly duping white audiences by black performers, a surface-level offensive shtick, and/or a critique of pop culture. A specific blackface trend that developed by the end of the 1800s was to do a blackface version of the president and prominent politicians. Blackface minstrelsy fundamentally and radically changed and infected American culture. By the era of the race film, blackface minstrelsy’s heyday had faded. However, the cultural scars that were left were still fresh and still hadn’t healed.

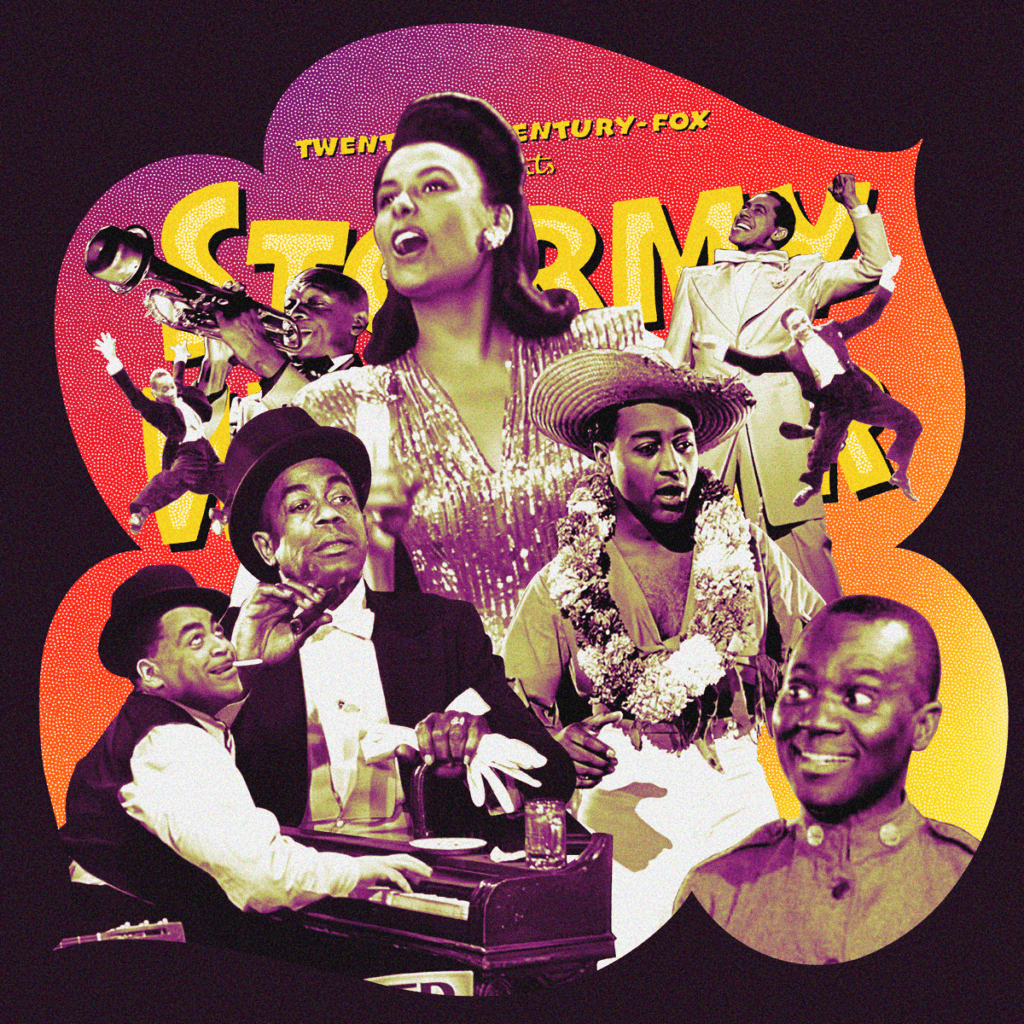

1943 was a landmark year for race films. It saw the release of two Hollywood musicals that were part of this race film experiment: Cabin in the Sky (MGM, Vincente Minnelli’s directorial debut) and Stormy Weather (Fox, Andrew L. Stone). This was the moment. Things were still far from equal but there was an attempt at giving them a chance by mainstream Hollywood. The catalyst for these even getting the consideration of becoming films was the then-rising star, Lena Horne. She was a trailblazer: one of the first black performers signed to a major film studio. Even though she had a studio contract, she was sparsely used outside of small support roles and cameos in musicals. If she was even a shade darker, her career would have panned out differently. With Stormy Weather, she was paired with some of the biggest stars of the era, Bill Robinson and Cab Calloway. This elevated Lena’s own rising star: she could hang with the era’s top talent. She was one of them.

Stormy Weather isn’t just a musical though, it began life as a song. From the start, it had ties to black culture and music. The song was one of several hits from composer Harold Arlen (who later composed for The Wizard of Oz) and lyricist, Ted Koehler. “Stormy Weather” debuted in 1933 and was sung by Ethel Waters at Harlem’s Cotton Club. Many others latched on and did their versions: Duke Ellington, Elisabeth Welch, Etta James, Charles Mingus, Judy Garland, Joni Mitchell, and Lena Horne (five different times), among others. Lena Horne’s 1941 version (her first one) proved to be the one that really exploded. It’s a classic torch song about a woman lamenting a lost love. It’s universal and there’s a reason it has stood the test of time. There was a backlash to the idea of making this, however. The film’s first music supervisor, William Grant Still was a popular black composer at the time. He left the production due to the appearance of regressive ideas and tropes. “His conscience would not let him accept money to help carry on a tradition opposed to the welfare of thirteen million people,” this preceded an attempted campaign to boycott the film and pressure Fox to present a better version of blackness for the screen. Emil Newman (composer of Laura and Lifeboat) replaced W. G. Still. The final film was a hit and critically praised. Not that critical and commercial success are markers of good art but it was paramount that this race film experiment to be a success. Yet, this push into race films was not followed up on in any major ways.

Having that foundation of race and art colliding is needed to get at why Stormy Weather is so revolutionary for its time (though things haven’t changed as much as we’d like to think) and punk as fuck. As “punk as fuck” as much as they could get away with, of course. The nearly 40-year age gap between Horne and Robinson is a lot. Though when you watch it, that element is barely acknowledged or even matters. The film carries a fun, manic energy that at times jumps into a near-parody territory, but the near-parody element is key to what makes this punk. The picture begins with Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson talking with some neighborhood kids, teaching some basic tap dance. It’s framed like a retro kids’ show starring Bojangles in a Mister Rogers role. He’s safe, non-threatening, and respectable for a national audience. This overly joyous innocence comes off as both genuine and too much. This is the first indication of the ridiculous and subtle influx that bucks the system within its limits.

Stormy Weather falls into that special category of satire like the similarly minded Bamboozled (2000) and Hollywood Shuffle (1987). That said, while it is an assault on those types of levels, it takes a restrained approach. It’s a compromised assault but still a savage attack on the institutionalized racism that built American entertainment. Bamboozled and Hollywood Shuffle are emanating unfiltered rage and passion without fear of repercussions. Pure expressions of black anger are a rare thing to witness in film. These are both cynical and ironic in how satire is handled. The point is clear: “fuck Hollywood, fuck the system.” While those approaches are satisfying, they were not possible in that specific way in 1940s Hollywood. Stormy Weather has that spirit of rebellion with a cast that’s nearly all black. And still, there is a raging passion behind each performer and performance.

The film tracks the lost few decades of black entertainment. It starts in the 1910s and ends in the early 1940s. You see how the older, creakier styles of performance had their heyday. There are palpable style and visual shifts in the performances over the 78 minutes. The highlights for the older style in the segments are the Tramp band riverboat performance, the Jungle stage show, and the Cakewalk. The Tramp band sequence is short and explosive, with fast rhythms and smooth proto-hip-hop lyricism. From the outside, the disheveled garb and style of speech appear to play into minstrel stereotypes, but it’s exaggerated for the performance to play up and embrace those stereotypes. The icing on the cake is Robinson’s tap routine. Tap dancing was a staple of minstrel performances, but Robinson isn’t tapping to impress white folks and demean himself, he’s tapping to show off and remind you why he’s one of the greatest American entertainers. Each vocalist has a different style emphasizing different stereotypes spliced with their manic aura; they radiate unfiltered fun and glee. It’s the shortest number in the short 78-minute runtime but the one that leaves a huge impact. The Cakewalk is a different story. This was a uniquely American dance that sprang up pre-13th Amendment on plantations to mock whites (but they didn’t know at first). The winner would receive a cake. This became a staple in minstrel shows and black communities across the US. The Cakewalk in Stormy Weather is one of the most elaborate sequences in the film (excluding one of the greatest dance scenes in cinematic history, aka the Nicholas Brothers’ closing routine), and has the element that would age the worst: it uses blackface. Just like the Tramp band, it’s exaggerated and shows how grotesque and absurd blackface is and was. The cake is a massive setpiece with blackface golliwog flower masks as decorations lining every layer of the cake prop. The detail and skill on display are beyond stellar and serve as an ugly reminder of plantations’ past; they aren’t the focus but they’re always in sight. Last, the Jungle stage show delves into “tribal” tropes, but with an Anansi trickster energy. Like the other two, this scene pushes out the humiliation and offers a sneaky sense of dignity. At first glance, these three sections appear regressive but that’s the magic: the performers are still dignified and human despite the framework they were forced into. The attitude in these three segments is clear with a smiling facade so the studio people were still happy. These are the film distilled into its purest form.

If Stormy Weather didn’t deliver on its 20 musical performances, it wouldn’t be remembered at all. The performers make this movie. It’s a showcase for the contemporary black talent of the time and proves a few simple things: these performers can match or even surpass their white counterparts. The list of legendary dancers, singers, and musicians cannot be oversold. The stars are Lena Horne and Bill Robinson, and then Cab Calloway shows up with 20 minutes left to nearly steal the show. Aside from the stars, the supporting cast is just as legendary: Vivian Dandridge (older sister of Dorothy Dandridge), Katherine Dunham, Dizzy Gillespie, Ada Brown, Fats Waller, Illinois Jacquet, Talley Beatty, Janet Collins, the Nicholas Brothers (who verifiably steal the show), and so much more. Stormy Weather lives and dies on the talent within. With a minimal story loosely chronicling the career of Bill Robinson and how black entertainment evolved from the World War I era to the 1940s, the performers and performances are both the style and the substance. The earlier performances feature the golliwog flower masks, blackface comedy routine, and other more stereotypical aspects, but by the end, these overtly racist slants are replaced with the empowering glitz and glamour that their white counterparts always possessed. The final sequence goes from Lena Horne singing the titular song to Katherine Dunham’s dance troupe to Cab Calloway to the Nicholas Brothers proving they were the most talented and athletic dancers of their era. It’s the victory lap that’s not just earned but the only way to end this celebration of talent.

As the film goes on, the performers go from being black entertainers to entertainers that are black. This ties into the legacy and importance of Bill Robinson. For decades, black entertainment and blackface minstrelsy were tied together. If a black entertainer wanted a successful career that crossed over, they were expected to put on the burnt cork. That was the case until Bill Robinson, which is subtly reflected in Stormy Weather. He was big enough to stop donning blackface and survive. Others followed suit soon after, and it mostly faded away. Using his life and legacy as the framework for the history of black entertainment is the easiest way to get the message across and show how things changed. The film’s statement is black entertainment’s past, present, and future. They are here. They are loud. They are talented. They won’t leave. The punk vibes are beyond palpable. It’s not subtle, it’s even not trying to be subtle. The studio still got their way after all but it was compromised on the sides of both parties. This again makes it strange that this was a flash in the pan, as the major studios backed off race films. Stormy Weather has been added to the National Film Registry making its legacy cemented and formally recognized. So in a sense, is Lena Horne the Patti Smith of the 1940s? Is Bill Robinson the Sid Vicious? Of course not, that’s ridiculous. Horne and Robinson were trailblazers and made the world a better place. Regardless, a proto-punk black studio film was made and blazed a trail for the future. ★