Blending science fiction and horror together on film often creates both excitement and dread among cinephiles. There is a feeling of excitement because of a universe of possibilities for clever filmmakers to create cosmic calamities on Earth, or terrors lurking in the darkness of outer space. There is also a feeling of dread because few filmmakers bother trying to come up with an original genre mashup, opting to ape Alien (1979) with little effort. The sheer number of rip-offs has created an entire subgenre for cinephiles to explore, but it can be said that Sir Ridley Scott’s classic space terror isn’t wholly original either. Don’t worry, I’m not trying to convince you that Alien is derivative trash (lest a face-hugger visit me as I slumber), but it wears its influences from past films onscreen, whether Scott acknowledges it or not. The film was pitched as “Jaws in outer space” to movie studios in order to get made (How many movie pitches referenced Jaws in the late ‘70s?); its screenwriter, Dan O’Bannon, would cite several films as key influences. One of them was a 1965 oddity from Italy: Terrore Nello Spazio, or, Planet Of The Vampires, as it was known in English-speaking countries, courtesy of American International Pictures. Written by prolific novelist/B-movie screenwriter Ib Melchior (The Angry Red Planet, Robinson Crusoe On Mars) and directed by giallo pioneer and horror master Mario Bava, Planet Of The Vampires is a dreamy, colorful sci-fi/horror pastiche, brimming with atmosphere (not just the planetary kind), acknowledging its pulp magazine and comic book roots. It’s a film that might have been forgotten had it not been for a certain cinematic xenomorph. Its lasting impact can be seen in George Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead, the aforementioned Alien, and several of the Alien rip-offs, namely Galaxy Of Terror, Future World (both from Roger Corman’s New World Pictures), and William Malone’s Creature (AKA Titan Find). If you’re looking for the titular vampires, I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed, as the English-language title is a red herring, likely as a result of the surge in popularity of vampire flicks in the mid ‘60s, courtesy of the resurrection of Christopher Lee’s Dracula.

After receiving a mysterious distress signal from an uncharted planet, two spaceships, the Argos and Galliott, attempt to land. In an inexplicable trance, both crews start to attack each other and only quick-thinking Captain Mark Markary (Barry Sullivan) of the Argos is able to stop his crew from killing each other and thus destroying the ship. The Galliott crashes and the Argos crew recover from their hypnotic state in time to land on the planet safely. They discover the Galliott’s crew are dead, having killed each other, including Captain Markary’s younger brother, Toby (Alberto Cevenini). As most of the Galliott crew are locked in the bridge, Markary orders his crew to bury the bodies that can be recovered and to break into the bridge to retrieve the others. When they return with the needed tools, the Argos crew cannot find any trace of the remaining Galliott bodies. A couple of the Galliott crew show up to the Argos to ask for help, but Markary finds their behaviour peculiar. As members of his crew disappear while the Argos is being repaired, Markary investigates the source of the alien transmission: is it genuine, or is it a trap?

Planet Of The Vampires was released in 1965, back when science fiction was merely a vehicle for drive-in fare, featuring radioactive monsters or cheap-looking rubber aliens attacking astronauts in rocket ships. Most of the good stuff was on TV, courtesy of two anthologies, The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits (Star Trek was busy filming its second pilot, this time with William Shatner, so it had yet to air), usually offering morality plays with a twist. Planet Of The Vampires was financed by AIP with teenagers in mind, but Mario Bava created something wholly different, a mix of sophisticated visuals and B-movie plotting that satisfied studio executives, teenagers, and cinephiles.

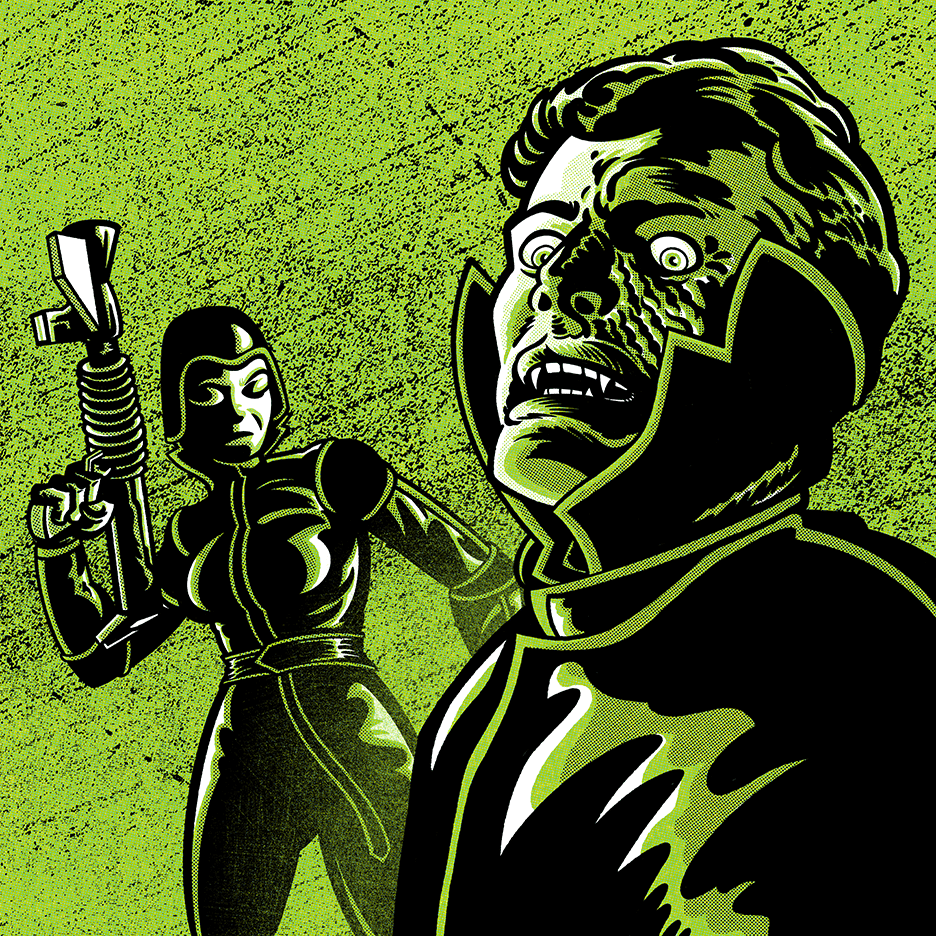

Filmed for the ultra-low cost of $200 000, Planet Of The Vampires is not an epic Hollywood production (for comparison, the first Star Trek pilot, “The Cage”, filmed at the same time in 1965, cost $630,000 and it was an hour-long TV show), but Mario Bava employs several cinematic tricks to fool the viewer into thinking the film has a significantly bigger budget than its reality. Most of the special effects were not created with optical printers or animation by technicians in post-production—they were performed in camera as they filmed! With such a paltry budget, it’s no wonder a visual genius like Bava and his film crew came up with creative solutions that saved money and time. The spaceship model, used for both ships, was filmed in a fish tank and the planet’s cloudy atmosphere was created by adding cotton wadding, using camera angles to create the illusion of movement. The ship itself is a combination of the typical saucer design (even Forbidden Planet, a clear influence on this film, uses a saucer design for its ship) and insectoid design, its multiple landing gears at the bottom of the craft suggesting a galactic beetle flying through space). Viewscreen images were not super-imposed in post-production, but featured the actors appearing on the other side of the constructed set, behind transparent plastic. The Argos’ giant control room was shot in forced perspective, creating the illusion of a bustling spaceship. With its limited budget, an elaborate control room couldn’t be constructed, but Bava places various computers and futuristic blinking lights in the foreground to make it seem like a bustling nerve center of operations. The floors and walls are all cool metallic blue-grey and the ship’s interiors have a clean, minimalist look that suggests highly-advanced engineering rather than cheap production design. The Argos crew’s high-collar black leather uniforms are visually stylish, if somewhat impractical for everyday space wear, but the collars and rubber headpieces create the film’s only vampiric vibe, a mix of Dracula and ‘60s catsuits (the suits look best when the crew wears their yellow helmets when taking strolls outside the ship, on the planetary surface). As I watched, I couldn’t help thinking that maybe this film influenced Marianne Faithfull’s memorable motorcycle gear in The Girl On The Motorcycle, but I’m not a fashionista, so I’m probably very wrong. Most of the attractive Italian cast looks fit and snug in their costumes while American lead Barry Sullivan, already in his early 50s and jowly from too much booze and cigarettes, looks uncomfortable in his spacesuit, likely worried that any bloating from the film’s Italian catering would cause serious damage.

While no vampires were harmed (or seen) during the making of this film, zombie fans will be delighted to see dead crewmembers resurrected, bits of sticky flesh hanging from open wounds, as they scurry between both spaceships, causing Captain Markary multiple headaches. His crew keeps burying the dead in metallic tombs on the surface, only for the space zombies to undo all that hard work just to cause a bit of mayhem. Unlike Romero’s zombies, these space zombies can talk, as the bodies are controlled by non-corporeal aliens! Yes, this tried-and-true staple of science fiction pulp stories is employed by Bava to explain how the mysterious signal at the beginning of the film is actually a ploy to attract curious spacefaring beings. The aliens want corporeal bodies, living or dead, and ships to get the hell off the planet and return home. Plots were never Bava’s primary concern: if you’re a persnickety science fiction fan, you might tire of the endless back-and-forth trips between spaceships. In true pulp magazine/comic book fashion, the captain has a very alliterative name—”Mark Markary,” which gets my vote as the silliest spaceship commander name in sci-fi history (it doesn’t roll off the tongue like “James T. Kirk”). Sullivan was forced upon Bava by AIP, so maybe the director changed the name as a retort to the studio meddling. The exploration of the planet surface might bore some viewers, but the misty, windy, nocturnal environment creates a foreboding tone, adding tension to the cosmic horror. Who wants to wander around on a dark and foggy planet? Bava’s planet set is creepily effective in its simplicity—who knows what kind of unseen alien creatures lurk behind the paper mâché rocks and mountains?

One of the most memorable scenes in Planet Of The Vampires is when Captain Markary and crewmember Sonya (Norma Bengall) investigate a nearby derelict ship, what they believe to be the source of the distress call. It’s this part of the film from which the Alien filmmakers borrow heavily: Markary discovers a giant alien skeleton, another victim of the non-corporeal aliens, and its very unusual spaceship (replete with cosmic tuning forks). Bava delights in Markary reeling from the very-alien nature of the derelict ship, using sound and color to convey a universe in which not all spaceships are created equally. Markary’s misadventures in the derelict ship nearly get him killed, but he continues his mission with steely determination. He might not understand everything that’s happening on the planet, but his befuddlement won’t stop his desire to send his surviving crew home, even if he has to endure a twist ending. Twist endings were commonplace in genre cinema, but Bava makes certain his twist has maximum impact on the viewer. Is it a happy or downbeat ending? That’s for you, gentle reader, to decide.

Mario Bava’s Planet Of The Vampires is an engaging and colorful mix of science fiction and horror, and it’s clearly an influence on Alien. Even if the plot is fuzzy and the Italian cast indistinguishable in their leather spacesuits, it’s an impressive display of style over substance, a visual confection that will delight genre fans. Bava continued delving into genre playfulness with forays into the spy and comic book worlds with Dr. Goldfoot And The Girl Bombs (1966) and Danger: Diabolik (1968); sadly, he never returned to outer space. Despite lacking creatures of the night, Planet Of The Vampires is a memorable space chiller courtesy of an Italian filmmaker who used his visual sensibilities and creativity to overcome a minuscule budget. What was once considered cheap exploitation fodder is now cherished today as a remarkable work of genre art.