Any good slasher movie worth its salt gives us a villain that has some traumatic event that sets off their murderous frenzy – their “trigger,” if you will. Sometimes it’s horrifically tragic, sometimes it’s tragically hilarious. Sometimes, there’s no motivation at all. And sometimes, there’s too much motivation. With Triggered! we’re singling out one insane individual from some of the best and worst slasher films to see if we can make sense of the method behind their madness. For this installment, we’re focusing on the maniac behind the slayings in 1981’s The Prowler, Sheriff George Fraser.

In October 1981, film distributors Sandhurst Films released Joseph Zito’s The Prowler both to theaters and ultimately mixed reviews. The film (also known as Rosemary’s Killer — which adds a lurid yellowed paperback-meets-Danielle Steele/V.C Andrews touch to the tale of scorned lovers — and/or The Pitchfork of Death, a title that sounds like some low-grade direct-to-video trashpile) received only a little love in the box office receipts tally, earning less than a million dollars, which incidentally was the film’s budget. The Prowler would clock in at 135th place for the 1981 U.S. Box Office, but still, all was not lost for the eerie, New Jersey-lensed slasher; today it ranks high on Paste Magazine’s list of best slasher films, declaring it one of the 50 best of all time (by the way, the list itself deserves a read, since the article actually respects the sub-genre), and its military fatigue-clad villain comes in at number 11 on L.A Weekly’s list of greatest slasher villains. Thanks to grindhouse auteur William Lustig’s home video shingle, Blue Underground, The Prowler finally received its due. And through this, Tom Savini’s gruesome makeup handiwork got to be seen by audiences new and old.

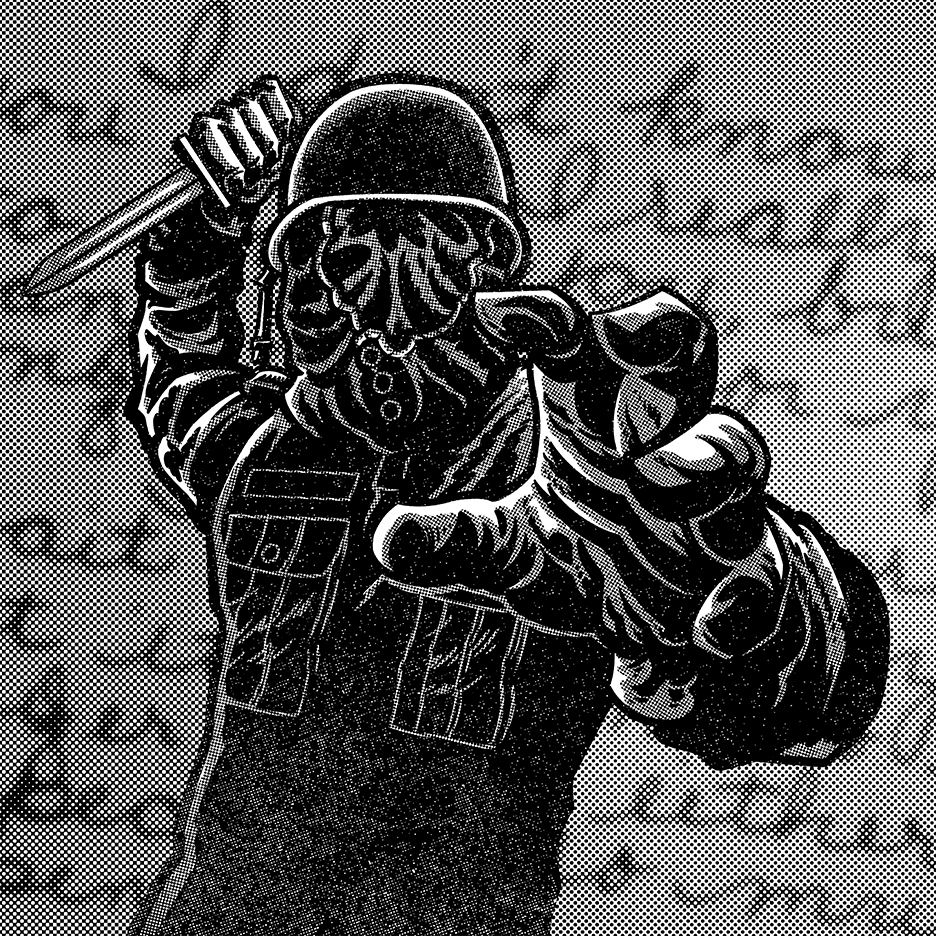

Perhaps The Prowler doesn’t stick in the heads of most casual horror fans, though, because of the real lack of unique features in the villain’s costume; he mainly just wears a combat soldier’s get-up. The Prowler often gets stacked up against My Bloody Valentine (which usually wins the “who has a better costume” argument) because their plots are sort of similar in a “Dante’s Peak/Volcano” kind of way. Both films center around a town resurrecting a long dead tradition that they had put off doing because of a past tragic event. In The Prowler, that event happened in 1945: a maniac slaughters a young gal named Rosemary – who had, as the film begins, recently sent a breakup letter to her boyfriend serving overseas – and her new beau by shish-kabobing them with a pitchfork. Some 35 years later, when the local youths bring the dance tradition back to the small town, it triggers the killer to again suit up and slay. At the film’s head-splattering climax, it’s revealed that the titular prowler is Sheriff George Fraser, the recipient of the letter Rosemary had penned all those years ago. It seems the dance being brought back was maybe just too much for him to handle. “The jilted lover” is an interesting take for the slasher genre, usually that sort of angle is reserved for “just desserts” entities like EC Comics and its cable television adaptation, Tales from the Crypt. But there’s undoubtedly more to the story than “heartbreak leads to murder,” giving The Prowler a historical edge over other run of the mill slasher titles.

As with most legends that tie into matters of historical significance, the origin of the “Dear John” letter is unknown, though its beginnings can mostly be woven into the fabric of World War II. Considering that, generationally speaking, males of military age by the time World War II was in full theatre had been previously christened with the name John (it was number one for most popular names from 1900 to 1923, according to the Social Security Administration, and only dropped out of the top ten in its popular name ranking in the year 1987), it became an effective placeholder to get a point across – a quick and dirty generalization, similar to how most unidentified living or deceased males are called “John Doe.” It made it so that any male military member could pick up the letter, see the words they feared the most, and could move on. As an example, one writer disclosed some of the thought process of the letter, courtesy of Democrat and Chronicle out of Rochester, New York – a letter provided to them in August, 1945: “Dear John,” the letter began. “I have found someone else whom I think the world of. I think the only way out is for us to get a divorce,” it said. They usually began like that, those letters that told of infidelity on the part of the wives of servicemen. The men called them “Dear Johns.”

A story out of the Vietnam War, via an excerpt from Chuck Gross’ 2004 novel Rattler One-Seven: A Vietnam Helicopter Pilot’s War Story, revealed this sobering statistic which undoubtedly fueled the already turbulent trauma caused by the war. Though it takes place in a decade far removed from The Prowler’s timeline, it can perhaps provide some insight on the state of mind of Sheriff’s Fraser’s irredeemable actions: “I heard that Vietnam caused more ‘Dear John’ letters than any other war in our history. I felt that these Dear John letters gave us a good indication of how our society and its attitudes towards sex, loyalty and devotion were changing. We had a lieutenant in our platoon that was in his early twenties. He was an easygoing, nice type of guy, who was always talking about his wife. One day he received a letter from her, and it was not the type of letter that he had wanted to receive. Overnight we noticed the effect that her letter had on him. There was nothing worse than getting a Dear John type letter from your wife or girlfriend and not being able to go home to try and resolve (or dissolve) your relationship. I felt sorry for those guys. As for this lieutenant, he suddenly turned very inward and started volunteering for every dangerous mission that came along. It looked to me like he was trying to get himself killed in combat. I thought that was really sad.” Reading this, one can begin to hypothetically formulate the type of violence that begin to swirl in Sheriff Fraser’s head and, as with Pamela Voorhees’ story, not condone the level of violence he committed and will continue to, but perhaps empathize with the hurt he felt when he received his own “Dear John” letter.

It’s one thing to privately react to any romantic rejection in pain, so long as our thoughts don’t turn to self-harm. Rejection stings greatly, and there isn’t a man or woman alive who disagrees with that. But empathy flies out the window once that rejection morphs into a reason to harm the rejecting party through mental, verbal, or physical harm, and doubly so if the anger turns homicidal. The pattern in males to commit murder against females is commonly known as “femicide.” It may not be surprising to know that femicide is most common in the South. In femicide, there are always a few similarities for each act. It’s most often the husband who commits the murder, with the victim almost always being the wife, in addition to the new male in her life. They always seem to be the same race, and the same age; or the male is older and befitting what would presumably be an impulse crime, the weapons are always guns, knives or beatings. An article from the New York Post details a moment in East Harlem in May of 2019, where an unnamed man, jilted by his ex-girlfriend, shot her new beau in the abdomen–a gunshot that would lead to the end of his life. Thankfully, she survived a shot in the leg, but often so many female victims of violent males do not get away so easily.

Being jilted by a lover is not the only motive one may have for murder, especially one committed by a person who served in war, a time where the line between moral and immoral acts becomes practically invisible. The acts one may witness in service of their country against enemies may be, via Science Direct, “potentially morally injurious events, such as perpetrating, failing to prevent or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs.” When one witnesses these types of events and is already potentially unstable due to outside influences, a volatile mental concoction can already begin formulating. There are numerous factors that can contribute to a veteran killing his fellow countryman on American soil; these stressors (which aren’t always combat-related, for instance, problems at home), post-traumatic stress disorders, and drugs or alcohol can give the final, influencing push to go out and commit the unthinkable. An individual doesn’t have to suffer from PTSD to understand the toll that weighs on one’s brain sometimes. Researching and reading up on stressors, post traumatic and the like, one can begin to see where mental health commonalities spring up. Speaking from personal experience, suffering from, say, social anxiety can begin to feel like weighted blankets are being thrown upon our brains. And our thoughts–our voices–feel smothered. The common reaction to feeling that way is the typical flight or fight response–again, from personal interpretation – and so we begin to mentally thrash out, trying to get our thought processes heard amidst the muffling of those weighted blankets. In most cases, when we do finally manage to get out from under our own mental suppression, it is under the guise of a primal, mental scream that isn’t designed to hurt anyone, whether it be strangers or the ones we love. Others simply do not have the rationale not to allow their mental rage to take them over, and in the case of our emotionally unstable Sheriff Fraser, when he comes flailing out from under this metaphorical blanket it ends up dangerous for those around him.

The effects work Tom Savini did for The Prowler is some of his most memorable, yet unheralded work: from the gnarly pitchfork kill the film begins with (the foot pushing the ‘fork in deeper is shudder-inducing), the migraine-lite bayonet kill which regularly sticks with viewers (the eyes rolling up in the victim’s head is terrific shorthand to get the pain of the killing across, and had that special spice of a nightmare that always accompanied the on-screen killings Savini engineered). Ditto for the slit-throat-via-bayonet: the choice to leave the implement wedged in the neck of the victim is phenomenal. The shower kill is a nice example of how a scene can shift from titillating to horrifying once murder is brought into play, and it shows that Savini is not one to rest on his laurels. Savini always manages to keep thinking of imaginative ways to present his effects and push the limits of what latex and fake blood could do on the silver screen. There’s a weird subversiveness that largely goes unremarked upon when writers discuss the film, in that Tom Savini constructs these murders at the hands of someone, who like he, served in the military. Joseph Zito’s wonderful direction on the feature must also be mentioned, shouldering The Prowler with solid atmosphere, especially when it becomes a haunted house movie around its Second Act. Zito directs the stalking and murder scenes with a joie de vivre, proving the solidity of his and Savini’s collaboration (in that, we can also consider their later efforts on the brilliant sequel, 1984’s Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter–a film which had a similar shower jump scare with a dead body before it was deleted).

The actors turn in adequate performances appropriate for the slasher sub-genre, despite a few interesting wrinkles in the usual hack and slash template (the final girl is made aware of the killer long before the climax, and a couple go off to make whoopee and survive–both rarities in the body count genre). Courtesy of the writers (one of whom is Neal Barbera, son of the animation titan), the film moves through some predictable elements, like the killer’s identity (he goes off on a fishing trip and then the killings start? Gee, who could that be?). Also, casting a relatively well-known actor (Farley Granger as the Sheriff, who had worked with Alfred Hitchcock in the late ’40s and ’50s) and then having him leave for the majority of the feature is also a not-so subtle clue (though I do get tickled at the laziness of the motel clerk as the heroes attempt to reach the sheriff to alert him about the killings. He just wants to play his cards!). The film provides two Red Herrings – the mentally disabled general store worker named Otto, and gruff character actor Lawrence Tierney, playing Major Chatham, who peeps on the female characters and then completely disappears for the film’s climax with nary a death scene or explanation (Hey Movie, learn how to Red Herring right!). Chatham is especially noteworthy, considering his relationship to the film’s most important victim – his daughter, Rosemary– and it leaves viewers to wonder about this oversight. At least the other Red Herring shows up to mostly save the day, until he himself becomes Sheriff Fraser’s last victim.

When Sheriff George Fraser brutally murders Rosemary and her lover, we know that he’s committed an unconscionable and immoral act. From a pure storytelling standpoint, this would be the end of his rampage – the act that triggered him has reached its logical endpoint. But alas, horror movies have to make a profit and thus the killings resume. But why do they need to resume? That’s kind of the question we want to ask, right? There are at least two logical points to figure out. The first, Sheriff Fraser is feeling immense shame that he killed his beloved Rosemary in a fit of passion, and therefore by going out and killing in a fit of madness, he’s wanting to silence the internal shame he’s lived with for 35 years. Or the other one, which is that he’s lashing out violently because of the graduation dance’s metaphorical implication. One can certainly relate to the anguish of a long-forgotten, deeply painful memory resurfacing, especially one that has romantic implications. For the Sheriff, the last time a dance occurred, he saw his beloved Rosemary having a moonlight hookup with another man. A new dance makes that simmering, long-forgotten rage come to a boil, and he needs to get the violence out no matter his tangible connection to the victims. And like most triggered and deranged villains: no matter what.