“If God wanted that movie to be good, He would have willed it so from the beginning.” This sort of Greater Plan attitude is the subconscious spiritual implication of a capitalist art industry. While the technology exists, on an affordable consumer grade, to allow any aspiring filmmaker to buy a blu-ray, import it into their computer, and create a new edit of any film, the results are relegated to the fringe world of exercises, hobbies, and fan edits. Torrents are full of Star Wars prequel edits attempting to purify what many devotees consider George Lucas’ sacrilege. These edits are works of a faith closely aligned with the human devotion to mythology. They fly in the face of entertainment industry dogma. Unfortunately for those pouring their souls into these edits, that industry is the status quo so they are not widely viewed as artists. They are belittled as religious freaks and cultists. They are also often criminalized.

In a small society, where mythology is passed down through oral traditions, tales mutate over generations. They adapt to reflect both the changing world and the personality of the teller. These stories are not owned, they are participated in. They are a part of the ongoing cultural conversation. In the world of big-budget films, the cultural myths are not just carved into stone, but guarded by teams of lawyers. Those wishing to participate in mythology run the risk of punishment. This sort of fortress of belief is not new though. Organized religion often becomes a bureaucracy dedicated to establishing what the canonical texts are, who the priests are that are allowed to communicate them, and how adherents are allowed to worship. Then, at points, new religions successfully break off from the establishment only to become their own forms of militant dogma.

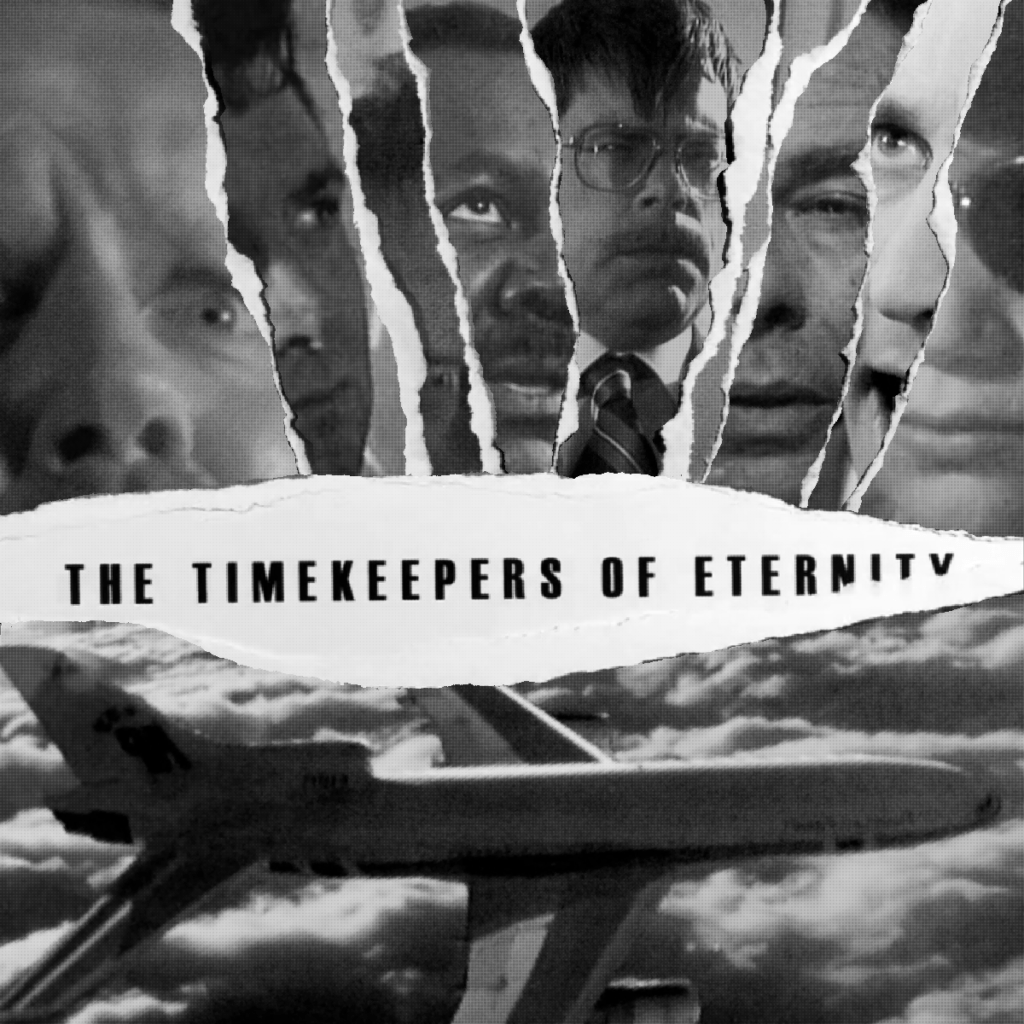

So what happens then when a Made-For-TV movie from the ’90s, that has failed to become a part of the cultural consciousness but is still protected by angelic attorneys at law, gets transformed by an editing outlaw? This is the case with Aristotelis Maragkos’ work of sacred art The Timekeepers of Eternity. At the simplest level, this is a fan edit of the movie The Langoliers. Anyone who gets to see Maragkos’ work will passionately agree though: that description fails to address every important aspect of what the filmmaker has done. But is it too pompous to consider this re-carving an act of a prophet?

The original source material here is Stephen King’s novella The Langoliers. While there is more than enough cult surrounding King to have made the shortcomings of the televised adaptation a disappointment, it is also one easily forgotten. No one in the mighty Temple of Entertainment is forcing this filmic misfire ~ most famous for its crude use of CGI rabid-Pac Man monsters ~ to be canon for worshiping King’s work. If Maragkos had merely gone into the film and tightened up the editing, removed any scenes that make the movie drag, and replaced the CGI creatures with something that look less laughable, this may not have even made waves in the torrent world of fan edits – because no one really feels the need for this sort of justice. Did Maragkos do all those things in his edit though? Yes, he did. Yet that is only the most surface level of what was manifested.

The ambition of craft in The Timekeepers of Eternity would sound daunting as a pitch. The fact that Maragkos actually did it is such a work of devotion on its own that it should instantly establish him as one of the great upcoming filmmakers. While the source material of The Langoliers is all live-action, The Timekeepers of Eternity is an animation. Every frame appears to have been printed out on a Xerox machine. Whether that was an actual physical process or a computer filter doesn’t matter [Editor’s Note: the film was made using actual paper.]. The result feels handcrafted with every moment glowing with the care placed upon it. This on-paper look allows the editing to move into unique territory where the frames get torn, crumbled, and manipulated both by diegetic occurrences in the narrative and as a result of Maragkos’ omnipotent voice reinterpreting the story. Frames will tear and reveal other scenes, allowing the viewer to witness multiple moments in time at once. These simultaneous observances create parallels between the characters and themes unseen in the source material. Tying the approach together is the antagonist’s nervous habit of tearing strips of paper apart. When the monsters finally appear, they too tear the paper world of the film apart. Unlike The Langoliers which depicts these reality devourers as blobs of razor-sharp polygonal teeth, The Timekeepers of Eternity depicts them as sentient shredded spaces in the film itself. It looks cool, which is an improvement, but the ways it deepens the storytelling is where this becomes truly sacred art.

Perhaps the most significant parallel that this torn-paper editing approach creates is between the antagonist and the protagonist. The antagonist is a highly strung businessman on a self-determined path of career suicide. It is his own sort of way of lighting himself on fire to protest the toxic world of corporate life that he has dedicated himself to since the traumas of being an abused boy. The protagonist is a blind child with an unexplained psychic link to the businessman. Through various torn displays of both characters at once, a sense is developed that these two characters are flip sides to the same coin. As a pair, they are a living example of how childhood innocence and purity can be corrupted, turning that child into a form of evil as an adult – particularly through capitalist ambition. The emotions of the businessman are uncontrolled like a child’s. The child’s behavior is wise and measured beyond her years. They are both the same person but also torn apart from each other. The editing reunites the two sides, but much like the temporal medium of film itself, this reunion is temporary and, ultimately, doom is waiting for all.

The biggest story arc change Maragkos makes is in turning the finale into a tragedy. Ultimately, there is no escape from the creatures / from time itself. The only true unity humanity has is in the here and now. There are no opportunities in the past because it is torn apart into nothing. The adult is doomed despite the purity of their childhood past. The child is doomed because they must become the adult. The rest of the supporting cast and the story itself are doomed because every film must eventually end. Unless…

Unless storytelling is allowed to be a part of the cultural conversation – evolving through each subsequent storyteller with the passion to change and make the mythologies their own. Kept under lock and key, mythologies become dead ends; they become sites of religious conflict. Maragkos shows with The Timekeepers of Eternity that artists revisiting works can be much more than acts of improving flawed work; it can be a way to open up deeper meanings that will impact viewers’ souls in equally meaningful ways. It is hard to know what the fate of The Timekeepers of Eternity will be, given the uncertainty in rogue use of intellectual properties. If Rodney Ascher’s Room 237, made entirely from unauthorized Stanley Kubrick footage, can ultimately see an authorized release, there may be hope here as well. If the rights owners of The Langoliers are smart, they’ll license The Timekeepers of Eternity and release both together as works of art inseparable from each other. That would be the wise move. But perhaps they’ll choose to act like an emotionally erratic man-child instead. ★

The Timekeepers of Eternity is an experimental film shown at Fantastic Fest in 2021, but may not be on the radar of the average filmgoer. For more information on the film, please take a look at the Square Eyes Film site or go to director Aristotleis Maragkos’ page.