Every Christmas film is an autobiography of the Spirit of Christmas. Well, essentially at least. The vast majority of Christmas movies, which most likely at this point bear the Hallmark or Lifetime insignia on them, all are films about themselves. They are films to remind the viewer what the films are: embodiments of the Spirit of Christmas. Obviously, these films have human writers and directors and crews, but they mostly have dogs for actors. In the end, especially if one wants to be devout about it, these humans and canines all come together thanks to the magical powers of the Season, so that the Season can tell everyone about the Season. Even the most common exception to this, the horror spoof of a Christmas movie, tends to still be just about that Spirit ~ sometimes critical, as with Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984), and sometimes as a dark way of reinforcing the norm like with Krampus (2015).

There is no narrative in the Christmas film canon that pulls this Spirit autobiography into a laser focus more than the slews of interpretations of Charles Dickens’ novella A Christmas Carol. Interpretation is an imprecise word to use though. A sampling of A Christmas Carol films from across the decades tends to show that these movies all walk their narratives almost exactly the same, beat for beat. From Scrooge (1951) to A Christmas Carol (1984) to The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992), these narratives rarely stray from the same plot points, down to the small details such as the knocker with Jacob Marley’s face on it and the vagrants looting drapes from the deceased Ebenezer Scrooge. Even in the Muppet version, the grand variations are all puppet gag inserts that serve as comic relief to the otherwise held-in-tact storyline. When Disney used Mickey and a large cast of recognizable cartoon cohorts to tell this tale, they boiled the narrative down to a lean 26 minutes. Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983) does cast off many of the common beats in other variations and still shows the essence of the Spirit of Christmas is clear at a peppy pace.

What is the Spirit of Christmas though? With so many of these autobiographies, it should be easy to discern. In some sense, it is that family and love are more important than wealth. Scrooge is always led by the Three Ghosts of Christmas to regret his life after seeing that he shouldn’t have chosen money over his childhood girlfriend Belle. He is also led to see that the familial love in the households of both his nephew and his abused employee, Bob Cratchit, are what he is missing in life. Ultimately though, these tools for opening Scrooge’s heart lead to the true message of all the versions: altruism. This philosophy that seems to be the true essence of The Spirit of Christmas allows A Christmas Carol narratives to resonate with both conservative and liberal extremes alike. It can be seen as a reinforcement of trickle-down economics or a socialist call for absolute financial equality. Statistically speaking, since most people have less than others, it is a narrative for enjoying the experience of the rich getting knocked down a few pegs while hanging with some cool ghosts. Unfortunately, though, an examination of the final, post-Ghost of Christmas Future moments of any of these films shows something truly grim. Scrooge doesn’t merely open his wallet in order to open his heart. Scrooge immediately begins to spend his money to buy his way out of sin and into the hearts of others. In the 1984 version starring George C. Scott, Scrooge opens his blinds and hires a child to go buy the most expensive turkey for the Cratchits. Not only can Scrooge not be bothered to go do this labor himself, he tells the child that there is a bonus in it for him if he does it within a short amount of time, reinforcing common tactics of paltry incentives to make people work harder. Then, upon reaching the Cratchit household Scrooge does some variation of giving Bob a raise or making him a partner. This act buys away the bottled-up scorn the Cratchits have for Scrooge. Years of mistreatment and suffering, not the least of which is the near murder of their son Tiny Tim, are magically washed away by taking Bob into the fold of money-lending. This is a move that John Carpenter would cast a very critical light upon in They Live (1988) when the invading aliens buy off potential human naysayers with an appeal to their greed. The lesson here finds a way to be about the nobility of altruism without sacrificing the original danger itself, Capitalism. With this sleight of hand, the Spirit of Christmas as a means of redemption appears to be open only to the wealthy.

There are, of course, interpretations of A Christmas Carol that are more true to the concept of being a variation. In Beavis and Butthead Do Christmas (1995), Beavis’ true lesson is learning that he better have sex at least once before he dies. The porn spoof The Passions of Carol (1975) does what all porn spoofs do best: remind the viewer that one ultimate truth is that all philosophies are moot in the face of the human sexual desire. Perhaps the most well-known flip on the traditional story is Die Hard (1988) where John McClane is a Scrooge type putting his cop work before his family and marriage and ends up helping the Tiny Tim cop-variant, Al Powell, to overcome his handicap of being afraid of using his gun. While all of these are fascinating in their own ways, they also move so far from the theme of altruism that they do more to redefine or undermine this classic definition of the Spirit of Christmas than mend the cracks mentioned so far. Why else would it be so hotly debated if Die Hard is a Christmas film? All the elements are literally right there, but perhaps it strips away that essence in a manner that people demand a sixth sense of when granting a movie the seasonal badge of honor. Of course, McClane does so much more to reclaim love in his life than the usual Scrooge would, only reinforcing more deeply how much the Spirit of Christmas must specifically be about economic altruism. Regardless, these variations prove to have strayed further than can address the issues at the center of the original Dickens tale. It is here that the bleak interpretations of A Christmas Carol (2019) and A Carol for Another Christmas (1964) find a unique balance in being both very different but only enough to shed a brighter light on this narrative tradition.

In the understandably Twilight Zone-esque, Rod Sterling-penned A Carol for Another Christmas, Scrooge is changed from simply a greedy, rich miser to a symbol of the isolationist philosophy driving the Cold War and inevitable nuclear holocaust. Again, the beats remain true to the Dickens narrative, but with more dialogue dedicated to debates of ethical philosophy. Unfortunately, the Ghosts frequently fall back on shady argumentative practices. Scrooge, saddened by the loss of his son in combat, finds solace in a Cold War knowing that it means the exposure of troops to battle is minimized, if not erased. The Ghost of Christmas Past tells him that ground warfare is the lesser of two evils and nothing compared to the loss of life that nuclear warfare would cause. Later, when Scrooge proposes a similar argument, suggesting that the suffering in a few refugee camps may be less suffering than another World War, the Ghost of Christmas Present scolds him for tallying lives and not injecting infinite value to even one life. Finally, in the vision shown by the Ghost of Christmas Future, a sort of Neo-Liberal ignorance is put on display by the spirit, equating social anarchism with absolute nihilism. Strangely enough, the bloodthirsty cult seen living in the post-apocalypse presents the only joyful characters in the entire story. Yet, the conclusion, when Scrooge wakes on Christmas Day, contextualizes these dialogues in a manner that makes them fitting rather than poorly written. Rather than jump for joy and have a manic episode as so many in the Scrooge multiverse tend to, this one finds himself contemplative and gently remorseful but knowing he does not have the answers. He makes apologies to his family and admits that when it comes to an issue as huge as world peace, there is no reason for his anger or confidence in what should be done. As Scrooge is a symbol of a political stance more than of wealth, there is no display of altruism here, although he does slightly integrate himself with his staff a bit more that morning. Not exactly as friends, nor crassly as their master. This version, while not solving a lot of the problems seen in traditional tellings, finds a way to walk the same path while being reasonable about the existence of these problems.

It is the 2019 version of A Christmas Carol that does the most impressive work to truly address how Capitalism and Christian charity are at odds. In the first act, Scrooge speaks eloquently, even poetically, of his views on Christmas:

“Behold. One day of the year. They all grin and greet each other when every other day they walk by with their faces in their collars. You know, it makes me very sad to see all the lies that come as surely as the snow at this time of year. How many ‘Merry Christmases’ are meant and how many are lies? To pretend on one day of the year that the human beast is not the human beast. That it is possible we can all be transformed. But if it were so… if it were possible for so many mortals to look at the calendar and transform from wolf to lamb, then why not every day? Instead of one day good, the rest bad, why not have everyone grinning at each other all year and have one day in the year when we’re all beasts and we pass each other by? Why not turn it around?”

It is a reasonable stance that Scrooge ironically reveals the fault in moments later by expressing annoyance with a man who comes by multiple times a week ~ year round ~ trying to collect rags for the unfortunate. Whether and where there is hypocrisy though, the film continues to explore explanation. Scrooge is not merely a greedy man for no reason. He may not even be greedy at all. Instead, the objectiveness of money appears to be a solace for him after a traumatizing childhood that taught him humans are beasts. Sexually abused and abandoned, what the audience sees Scrooge go through evokes pity for the character in a way that no other version of this story can. That pity is then used against the audience as it is revealed that Scrooge has also sexually humiliated Mary Cratchit in years past. The story is complicated, much like real life, and Scrooge himself is made much more human for it. It also helps to distinguish something that earlier versions fail to: Scrooge may be the protagonist but that does not make him the hero. In the end, Scrooge’s true self-discovery is in realizing he doesn’t deserve any form of redemption and offers to trade his life so that Tiny Tim may live. On Christmas morning, Scrooge hands over money to his usual victims but reiterates that he still doesn’t deserve redemption. Mary Cratchit agrees and says she has none to offer him. Finally, the film ends by noting that the story is far from over, as does make the most sense for the monumental task of creating justice out of a lifetime of suffering both received and caused. It is important to note as well, in this version Scrooge explicitly states at the beginning that he does not believe in Christ. In the autobiographies of The Spirit of Christmas, it is fitting that Christ is almost never mentioned, as altruism’s basis relies on the preservation of Capitalism. Even Tiny Tim’s oft-quoted, “God bless us, everyone,” notably is delivered not by Scrooge and is tacked on in such a manner to grant divine redemption to all the characters regardless of class standing. By ending with this line, it avoids a clear need for inspection. After all, “It is easier for a camel to go through a needle’s eye than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” In this version’s admirable attempt to solve the riddle of the Sphinx of Christmas, it may fall into a similar trap as Die Hard though. By stepping away from that pleasant, ineffable feeling people expect from a seasonal story, the Spirit of Christmas itself may have been exorcised in the process of healing its cracks.

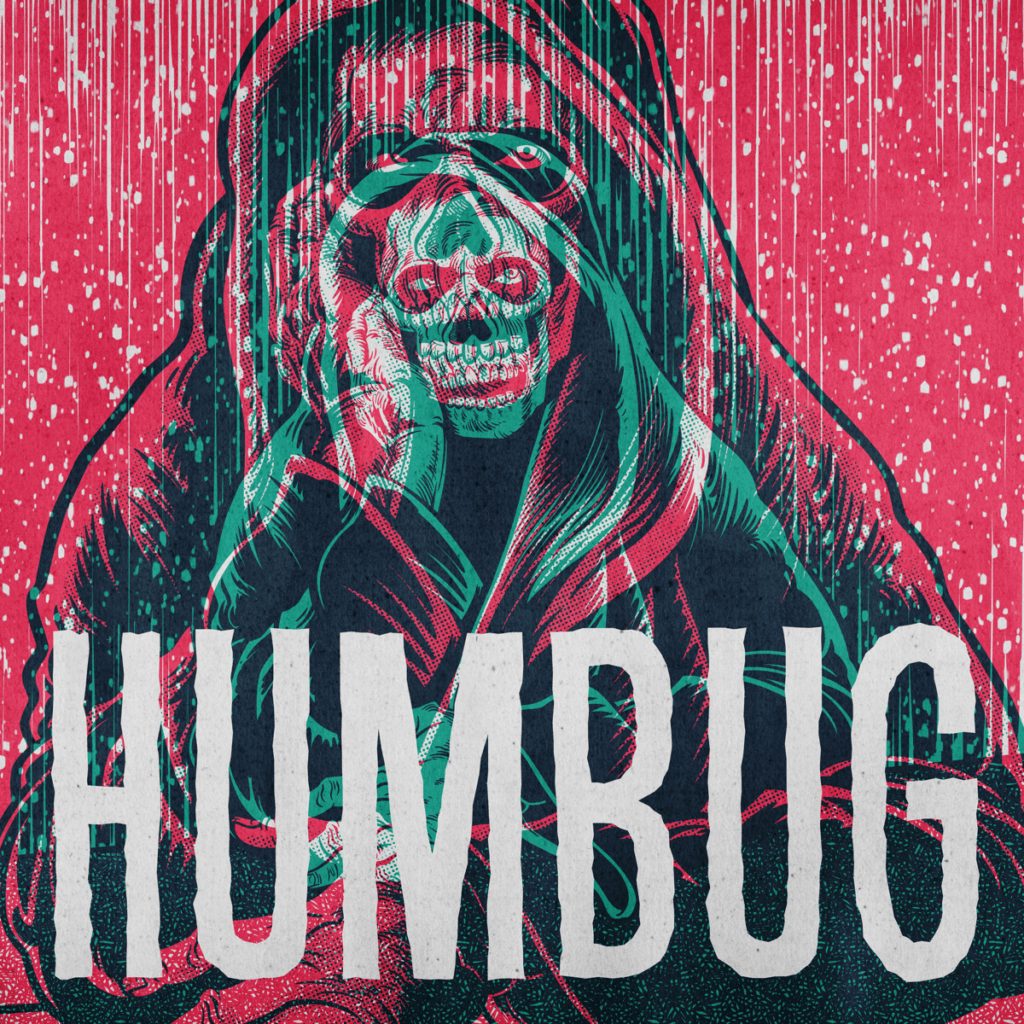

Ultimately, it is the reinforcement of the value of Scrooge’s wealth, as a tool for either good or evil, that muddles what exactly the Spirit of Christmas is in any traditional take. A variation where Scrooge is poor and has spent a life abusing the generosity and faith his family and friends have in him, where after being visited by three Ghosts, he discovers that he can’t simply buy his way into Heaven, could potentially be an enlightening flip. The original Dickens novella both coined the phrase “Bah, Humbug!” and popularized the blessing “Merry Christmas.” The legacy of this story seems to have contradiction inherently built into it. Does this matter though in the impressionistic medium of cinema, where the experience to take away is more than the sum of the parts? Of course, what may be the real problem here is that none of the films discussed so far star dogs in the lead roles. Dogs are clearly the ultimate avatar of the Spirit of Christmas, so all one really needs to do to celebrate the season right is watch An All Dogs Christmas Carol (1998). Surely a viewing of this platonic form of the story will bridge the impossible gap between Capitalism and eternal salvation, and at long last put the canine Christ firmly back in Christmas. ★