Vera Chytilova graduated from the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU) in 1962, but when she entered the Academy, she stood in front of a board of resident directors to acquaint them with why she wanted to study film. She looked them all in the eye, snarled her lip, threw them the finger while flipping a table (smashing no less than three bottles of Pilsner Urquell in the process), and defiantly told them she didn’t like their films. Of course that first chunk is speculation, but the latter bit is true, and is perhaps the punkest thing to ever have occurred in a film academy.

Chytilova, 28 when she began her studies, had decided to boldly buck against authority because she found her elders’ work boring. In the accompanying documentary on the 2018 Second Run blu-ray release of her most acclaimed film, Daisies, she notes her dispassion for their films by saying they were “so arranged” that the “form seemed to have gone rigid.” (Yes indeed, yawn.) Subsequently Chytilova set out on her filmmaking journey, resulting in multiple decades’ worth of her pushing the boundaries of what’s expected not only from a female filmmaker, but one who started her career amidst the restraint of a totalitarian communist regime. Chytilova has a number of rebellious films under her belt, but Daisies is definitely her most recognizable achievement, and thus probably the most significant title for this column.

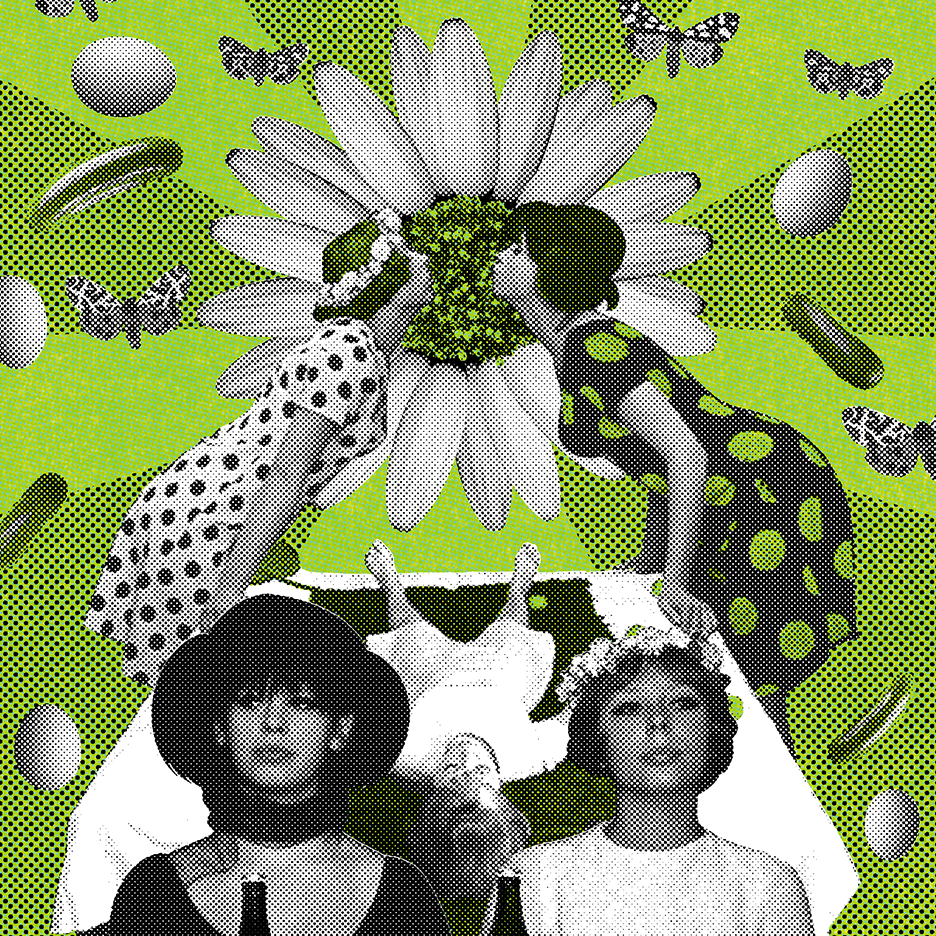

Let’s put it plainly: Daisies is a punk rock movie. The film’s political nature–a commonality among various types of punk movies–takes precedent with a majority of viewers, but besides that, what makes it so outstandingly punk is its use of farce. By definition, farce is hyperbolic, often cartoonish and ridiculous, using character mannerisms and reactions to driving plot events for comic effect. Other politically-dynamic punk-themed movies might make a move toward the more serious, but the farcical nature of Daisies gives it an edge not typically present in such dramas; a true form of subversion wherein the characters act both as reposed puppets and “rebel girls” who absolutely refuse to be puppets. It’s a case in which character tropes work for the characters rather than against them, adding flourish and humor to existential drama.

The film is also punk because it’s sneaky. Czech censors knew they should be afraid of it, but struggled to find a sensible reason to ban it. Eventually a makeshift reason would be named (the wasting of food), but what better way to get your transgressive message out than to make it so ambiguous that it confuses the censors? Punk is traditionally thought of as an “in your face” kind of thing, with often-faux rudeness, or insincerity in exaggerated tough guy antics. Instead, however, the world of Daisies is giddy, surreal, stylish, and well, dainty. “Form = Function” is cleverly practiced; Chytilova uses hyperactive editing and bright color gels mixed with a unique soundtrack full of absurd noise effects to ensure her audience is paying attention. Symbolism abounds in Chytilova’s imagery, but those stylistic choices aren’t limited to just the visual. Character traits that switch between riotous and feminine are an inspired bit of dichotomy; it doesn’t even hurt that the girls are basically interchangeable (they seem to be on the same levels of intelligence and maturity, share similar personalities, and both are called Marie). Despite Daisies’ anarchic makeup, the context is quite coherent.

As the world of Daisies is being established, we learn something catastrophic is happening. The cut back and forth between images of machine gears and exploding bombs is glaring evidence of this, but the Maries further our suspicions with their initial dialogue: the world is bad, so they want to be bad (some translations extend further than the word “bad,” choosing to use “spoiled” instead. “Spoiled” seems more fitting, given the story of these two girls that we’re about to consume, but we’ll stick with “bad” for this essay.). This idea itself is a bit of a farce in that it seems as if it’s being presented with a wink and smirk already, especially as the Maries’ discussion of it includes the two of them mimicking machine-like movements, robotically raising and bending their arms and legs as caustically-applied squeaky sounds accompany their motions. This is Chytilova’s planned chaos, her throwing the finger to her elder directors again by upending the reasons why their movies were stale. She’s using her characters as puppets just as they did, only her little beauties are goofy caricatures of the idealized young woman–in robot form. Chytilova is basically telling her predecessors “let’s call it what it is here, you’ve got your puppets, so here are mine.” In that, her form functions in a series of non sequitur meta comments — a daringly punk move, especially in 1966 Czechoslovakia.

The Maries’ bad behavior may have a few different functions, but to focus on one: Chytilova purposely set out to subvert the audience’s ideals of the typical female role. She comments on the “age-old fear men have of hysterical women” in the same Second Run documentary, saying, “I knew I had to make hysterical scenes.” Hysterical they are, from gorging on whole pheasants and cakes while tricking older men into buying them lunch to setting fire to paper streamers hanging from the ceiling of their apartment to ridiculously attacking each other with scissors resulting in daffy disembodied heads and limbs floating around the frame. It may go without saying this type of novel subversion is comparatively mild in modern times as society’s broadest expectations of women have evolved over the years. The meaning of this particular kind of subversion may have held much more weight in 1966 Czechoslovakia, but that’s not to say the then-revolutionary feel of it is lost to us today.

The farce of this story lies almost entirely in that hysteria, and part of that is due to Chytilova using other female tropes to subvert the “what’s expected in 1966” female tropes. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl, for instance, is admittedly somewhat tired of a topic, but is worth exploring in Daisies. Although the term was coined in 2007, many recognizable female characters ranging from Holly Golightly to Annie Hall have retroactively been fitted into the trope — some done more unjustly than others. So it’s fair game to say that even though MPDG wasn’t a “thing” in 1966, there could’ve been something in the zeitgeist that propelled Chytilova to take a stance against it. Maybe it was a general feeling that men should take women more seriously at that time, a hypothetical response to her own experiences at FAMU, or maybe it was just Chytilova penning a cautionary tale about men she saw continually having their nymphet cake and eating it, too (so to speak). Regardless of substantiation, the interpretation is fun to think about.

(In case any of us have forgotten–or somehow never knew, congratulations–what MPDGs are, they’re the quirky, energetic, insightful female characters in any given story who exist solely to help their male counterparts affect some kind of great change in their lives, to achieve some kind of existential awakening. The trope has come under scrutiny by men and women alike, with the real-world implications of the MPDG often cited as catastrophic, giving women the impression they should try to model themselves after these ultimately passive characters in order to be loved–just take a look at various young women’s Tumblrs and Twitter profiles that cite MPDG as a “brand,” and the development of the e-girl in recent times. Additionally, as supporting characters in men’s stories, The Atlantic notes MPDGs “send the message that a bright and sensitive young man can only learn to embrace life by falling in love with a woman who sees the dazzling colors and rich complexities he can’t.” So it’s really not fair to either gender to say (1) women are lacking in agency beyond an emotionally catalytic relationship to a man, and (2) men are too dumb and/or lazy to bring meaning to their own lives.)

It may be easy to lump the Maries into this category. After all, they’re attractive and seemingly carefree young ladies with an unconventional type of ambition. Again, they want to act out and be bad because there’s really no point not to. The world has gone bad, society has gone bad, so who cares? (This may be Chytilova’s comment on nihilism, but let’s return to that later.) The Maries are cute, flighty, and non-committal, and therefore always sought-after, and even the little attention they give is an energy that makes younger men feel poetic and special, and older men feel young and uninhibited again.

Either out of necessity or boredom (it’s not clear exactly which one, and actually may be both), The Maries spend a great deal of their midday time tricking older gentlemen into buying them lunch at fancy restaurants. The ruse usually goes that the brunette Marie lures a lonely-looking man into treating her, and at some point the blonde Marie (pretending to be her sister) shows up unexpectedly at the table to make the game more elaborate (and the lunch more gluttonous). The girls’ bad behavior here is layered; first off, gluttony is by most means a sin, and the way in which they thoughtlessly tear meat off the bone with their fingers and stuff their mouths with cake using only their hands is extremely taboo for civilized women. Not only do the Maries blatantly ignore society’s rules, they succeed in putting their lunchmates in a very uncomfortable position: embarrassed by their unclassy behavior, but not embarrassed enough to refuse them. It’s reminiscent of the classic Lolita story jammed into the span of an afternoon; the men impulsively want the girls as their dolls but don’t know how to handle their intensity. In this way, we can consider Daisies an exploitation of men and their tendencies toward the newly nubile female. The Maries are, essentially, out to capitalize on a (less humiliating) variation of what we know today as ddlg porn, but at the same time reject all the conventions of that kind of thing. The girls are definitely in control of the entire operation, laughing their way through the almost slapstick goodbyes they give their gentlemen suitors (victims?) at the train station after lunch. Hey, you know…maybe we have the Maries to thank for findom. They’re just being weird about it.

However aware of the MPDG trope she actually was at the time, Chytilova still turns it on its head. She’s using this trope before it existed in modern vernacular to not only say “to hell with what you think of women,” but “to hell with what you think you love about women.” It literally does not matter to the Maries how anyone regards them, they’re going to wreak havoc and have a giggle while they’re doing it. The Maries are disinterested in love, so any advances from even age-appropriate suitors go unrequited. While on the phone with a young man who’s clearly infatuated with her, the blonde Marie turns away from the receiver and says to the brunette, “I don’t understand why they say ‘I love you.’ Why don’t they say, for example, ‘egg.’” Marie isn’t playing into the trope, it’s so very inconsequential to her that this man is repeating that he loves her — he may as well be reading from the phone book. It seems as though the pair are pretty disinterested in sex as well, from how they barbecue sausages inside their apartment and carelessly cut them up with sewing shears (the motion is repeated later, but with bananas). Some may take this as an act of man-hate (the obliteration of phallic-like food items, obviously), but perhaps it’s more of a signifier of a deeper confusion or, really, indifference. Men are unimportant to the Maries, merely the supporting characters of their lives. It doesn’t matter how quirky or full of life the Maries are, they’re always in it only for themselves and their own entertainment. Whereas the typical MPDG seeks to impart some kind of appreciation or wisdom into their male friends, the Maries aren’t concerned with philosophy, they’re really just in it for the fun of it. Simply put, the Maries can’t be MPDGs. They’re too cool for that.

Chytilova’s use of farce extends beyond the MPDG trope, however. She clearly has a handle on using the ridiculous to point out the ridiculousness of her modern world. There’s one scene in particular which stands out: the Maries literally wander into a cocktail room in which a man and a woman are performing a lively song-and-dance number, stumbling into the duo before being ushered to a private booth away from the dancefloor. In what ultimately can be read as a comment on “real art” versus “trash art,” the Maries steal the spotlight from the dancers by becoming wildly drunk and obnoxiously dancing around their table. The audience is distracted by the Maries, cheering more loudly for them than the dancers themselves, and the camera focuses briefly on the annoyed demeanor of the upstaged female performer. Granted, again, this was 1966, but perhaps we can’t help but be reminded of flashy film or television whose only goal is to provide a cheap distraction for mass audiences (think: talk shows, reality tv, superhero films), emphasized by our romance with spectacle. The dancers are the “real” art here, being pushed aside by what amounts to little more than vapid, reckless behavior from Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie. Chytilova was not likely actively trying to insult her characters, but adopting this flashy, trashy behavior for even just this one scene is helpful in setting up what else is to come later on in the picture.

After another crazy excursion, the Maries are walking home on a countryish road. They pass several people on their walk; one man they take note of is a local gardener, and a group of cyclists zoom past them — none of whom give the pair even the slightest nod of acknowledgement. It’s especially strange because, oh yeah, the girls are awkwardly carrying several ears of corn they were able to swipe from a cornfield along the way because they needed something to munch on. “No one’s paying attention to us. What if we’re lacking something?” the blonde Marie laments. It’s a hint at existential angst; this time their sexy, wily charms have not worked on these men—who don’t even give them glances—so the Maries question if they’ve lost their touch. It’s a comment not just on the men, but on the women who decide to behave as MPDGs; if they don’t get the attention they’re used to, they are disappointed and saddened. To the Maries, something is obviously wrong, leading to an empirical question: “do we really want to be this way?” they may ask. Tailoring a persona, unfortunately, as many MPDGs may do, the crafting of it is an exhausting detriment, tampering with not only others’ perceptions of them, but their perceptions of themselves. So is the Maries’ existential angst tied to their manic pixie-ism? Probably. But it’s quickly dismissed by the girls skipping around and repeating what comes to be their mantra: “Does it matter?”

With all their emotional indifference, physical destruction, and the chaos brought by smashing several high society taboos, let alone completely obliterating what we can assume to be is an exclusive state dinner, the Maries continue on their journey of impulsive action and madness. To top it off, they have a strange kind of fashion show when it’s all through, leaving us to actually wonder if anything does matter. Are they lacking something?? At the end they’re suddenly transported to a scene in which they’re dipped in water on large beams like it’s a witch hunt, and then just as suddenly, they’re back in the grand food hall. Having just half-learned some vague kind of lesson, they try for redemption, cleaning up their mess amidst an audible backdrop of creepy, (actually, almost witchlike) whispering about how good they are at cleaning. The Maries hurriedly attempt putting all the stuff they’ve broken back together into something that might resemble a table setting, but with the china in large jagged chunks and glasses shattered, not any of it is even close to being functional. The damage has been done, it’s irreversible, yet they are so proud of their job-well-done. “We’ve worked hard, haven’t we?” they complement one another, as if they’re expecting a participation trophy. With this, we ask: does “trash art” amount to anything more than empty calories? We know damn well that the Maries know damn well they haven’t actually done a good job at all, and their insistence upon it is desperate and unfulfilling.

To drudge into the political, Chytilova’s comments toward the valorization of emancipation are nuanced. Many of her peers involved in the Czech New Wave might have taken on a strict liberationist view, but Chytilova seems to be pointing out that replacing socialism straight up with liberation is narrow-minded, and the Czech people should perhaps focus first on what kind of people they want to be. Sure, the girls break through the oppression of patriarchy by subverting how women should behave, yet they are shown stealing from a lady in the restroom. So what’s the cost of that breakthrough? What good is feminism if we’re still bad people? In the end we learn we can’t just throw the baby out with the bathwater, we can’t just be destructive and expect society to heal itself. We can’t abandon society. And when the damage is done, the damage is done. Chytilova certainly isn’t promoting a nihilistic view, even though the film is quite anarchic and destructive. It’s the introspection that Daisies inspires that pulls it out of that rut; “This film is dedicated to those whose only indignation is a trampled-on trifle,” the final frame announces, and is Chytilova very cheekily telling us to check ourselves before we wreck ourselves.

Daisies is punk because it uses farce to subvert commonplace female tropes such as the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, giving depth and agency to characters that would elsewhere be merely considered a “type” for a certain kind of man who’s seeking a certain kind of love. Daisies’ span of influence reaches everywhere from Laverne & Shirley to the Spice Girls (seriously rewatch the “Wannabe” music video and put it side by side with the smorgasbord scene in Daisies). We can’t exactly think of the Maries as role models, no matter how much they reject the principles of the burnt out manic pixie trope. But as weird, wild girls, we can take some of their best traits and apply those to inject some fun into our lives.