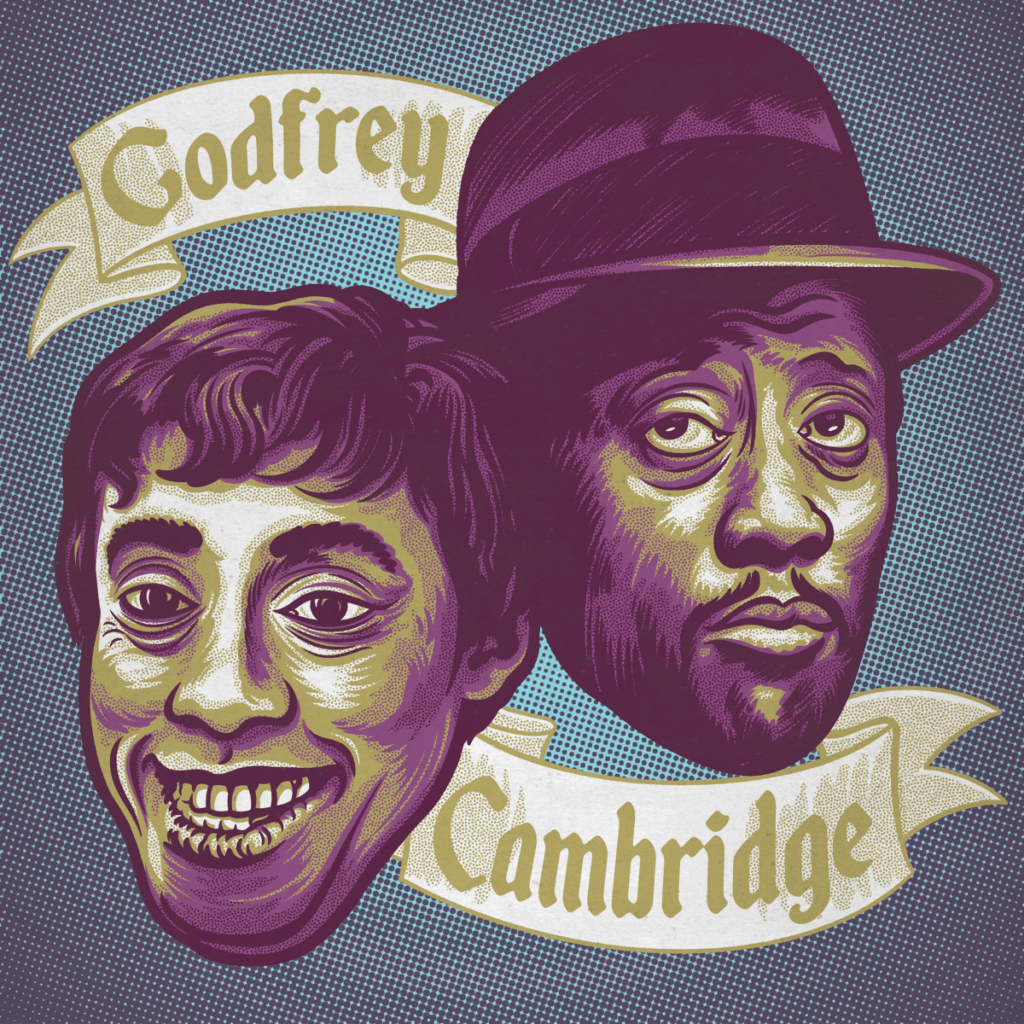

Godfrey MacArthur Cambridge’s star shone very brightly in the 1960s and 1970s; in a short time, he did it all – comedy, theatre, film, civil rights activism, and more. On May 27, 1970, audiences packed movie theaters to see one of the most talented and unique performers tackle contemporary black issues in two very different films. As the only starring roles in Cambridge’s film career, these are also easily his best films: Cotton Comes To Harlem and Watermelon Man.

Cambridge’s parents, Alexander and Sarah, were British New Guinea immigrants. Born on February 26, 1933, Cambridge experienced radical changes in culture at a young age, as the family moved from Sydney, Nova Scotia to New York City. Once he was old enough for school, his parents shipped him back to Canada. To them, the New York school system was not good enough; instead, he was sent to stay with his grandparents in Nova Scotia for grammar school, and back to NYC for Flushing High School. After graduating, he got a full scholarship for medicine at Hofstra University, but instead of completing four years, he dropped out after two and a half to pursue acting.

By the 1960s, black artists and entertainers had gotten a boost and started to really become a part of the mainstream. Some of Cambridge’s contemporaries were Bill Cosby, Dick Gregory, Nipsey Russell, and Redd Foxx. Of those, the one name that’s always left out and (reluctantly) understandably gets overlooked is Godfrey Cambridge. The answer is simple; he didn’t have the same career as his contemporaries. Headlining more films and TV shows, and in the spotlight on the stand-up circuit, many of them did have burgeoning acting careers, but acting came second to the comedy. Cambridge was a trained actor first before diving into comedy like his peers, but eventually the acting career overtook the comedy career completely. That said, he covered all arrays of performance he could reach. Cambridge explored more avenues and managed to excel at everything he tried, and couldn’t be pigeonholed into anything. He was picky with a purpose.

Cambridge first broke through both comedy and acting worlds in 1956: through comedy monologues on Jack Paar’s show for TV and the successful Off-Broadway production, Take A Giant Step for the theatre. 1957 was his first Broadway production as Butler in Nature’s Way. During all of this, he was also doing stand-up. Nature’s Way ran for 61 shows, which led to even more stage work that would have lasting aftereffects on Cotton Comes To Harlem. Cambridge even met his first wife, Barbara Ann Teer, during these early theatre years, but the marriage only lasted from 1962-1965. She worked in theatre, and in 1968, founded one of the longest-running black theatres and cultural complexes in the nation, the still active National Black Theatre in Harlem. But rather than going through all of Cambridge’s stage roles, two will be highlighted: Purlie Victorious and The Blacks.

Jean Genet, the prolific French writer and playwright, had a huge hit with The Blacks. It was one of the top non-musical off-Broadway shows for the entirety of the 1960s. The debut was on May 4, 1961, and it ran for 1,408 shows in total. The original cast was made up of many future stars including Mr. Cambridge, Raymond St. Jacques, Maya Angelou, James Earl Jones, Louis Gossett Jr., and Charles Gordone (of Ralph Bakshi’s Coonskin). Raymond St. Jacques would later co-star in a couple of films with Cambridge.

Purlie Victorious was not just a play by one of the greatest people of the 20th century, the legendary Ossie Davis, it was the first true high point for Cambridge’s acting career. The play ran on Broadway from September 28, 1961 – May 13, 1962, with an original cast featuring Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Beah Richards, and Alan Alda. This original run was both successful and critically beloved. Although awards don’t conclusively mean that much in the end, they are the ultimate sign of acceptance and trends. Cambridge was nominated for a Tony Award but lost to Walter Matthau. Other nominees (in other categories) that year included Charles Nelson Reilly and Donald Pleasence! Purlie became a film called Gone Are The Days! shortly afterward in 1963 with many of the original Broadway cast returning (notably, this would be Alda’s film debut). The play’s legacy continued with another run as a musical in 1969 with Cleavon Little (who would appear with Godfrey in an upcoming film) and Sherman Hemsley replacing Cambridge in the Gitlow Judson role.

Ossie Davis and Cambridge already had a professional relationship from the Purlie Victorious show and its film. That continued into Ossie’s debut directorial film, Cotton Comes To Harlem. Just to address the elephant in the room, Cotton is action/comedy from a major studio. “Blaxploitation” is not a genre; it is a term that covers every genre under the umbrella with films that had a black cast. Those films were both empowering and reductive all at once, with the major studios realizing telling black stories would make them money but still employed majority white directors and crew to create them (rant over). Cotton Comes To Harlem is an adaptation of the novel by Chester Himes, from his Harlem Detectives (aka Grave Digger Jones & Coffin Ed Johnson Mysteries) series. These were eight novels written and set in 1950s/1960s Harlem about cops Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson. If you read any of these before seeing Ossie’s adaptation of the 7th entry, you’re in for a surprise. The tone jumps from the grim, violent, and dark humor of the novel into a lightly adventurous, action-packed, and joke-filled popcorn flick. Himes filled his vision of 1960s Harlem with grim violence equally matched with grim humor. Gravedigger and Coffin Ed are rough cops who aren’t afraid to use violence to solve their cases; i.e., in the 2nd novel in the series, Real Cool Killers, a bartender breaks up a fight in a bar by chopping off a man’s arm with a fireman’s axe after the man drew a knife. Said man tries to retrieve the knife with his severed arm, but bleeds out before he can use it. Ossie Davis’ adaptation takes the spirit of Himes’ work and turns it into a fun action adventure joint. The nihilistic anger beneath the pages of the series is still there but is infused with a “Black is Beautiful” sensibility and upbeat attitude.

Cotton Comes To Harlem is a blast from start to finish. Now, where does Godfrey Cambridge fit into this? Cambridge stars alongside fellow theatre actor, Raymond St. Jacques. Aside from the tonal shift in jumping onto the screen from the page, the first thing that sticks out is the characterization of the lead detectives: Gravedigger Jones (Cambridge) and Coffin Ed (St. Jacques). Their chemistry is immediate and charismatic. From moment one, this is a different version of the story. It softens things a bit, but that is not a bad thing. Ossie following suit with the book’s tone would feel closer to a fresh Peckinpah knockoff with a racially flipped cast.

The plot is simple: $87,000 has gone missing, so the Harlem detectives are on the case. A mysterious bale of cotton appears in Harlem and it keeps moving person-to-person. A local “preacher,” Deke O’Malley (Calvin Lockhart, recognizable from Wild at Heart, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, and Predator 2), is running a scam reenacting the Marcus Garvey Black Star Line while Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed investigate the public robbery of O’Malley’s profits at a rally. O’Malley is caught, and a local homeless man, Uncle Budd (Redd Foxx), takes the money and moves to Ghana. The money was in the bale of cotton the whole time.

Just like Watermelon Man, Cotton Comes to Harlem deals with racism’s legacy. Except, it’s with the title’s MacGuffin. The mysterious cotton bale that rolls into Harlem isn’t just for a great name. Cotton really does come to Harlem. The question comes down to what it is doing there and why it is there. It was all part of Deke O’Malley’s ruse. A re-purposing of cotton, and having a black leader behind the scheme truly makes this an evil plan; storing the people’s stolen money from a scheme reminiscent of Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line in a cotton bale is insidious. On top of that, he poses as a religious leader. He took advantage of both the public’s personal finances and their faith. Everything about O’Malley is slimy, desperate, and purposeful. The cotton’s not just a visual reminder of the pre-13th Amendment era; just visually having a white bale of cotton in 1970 Harlem would stick out next to the urban landscape. The theme song “Cotton Comes to Harlem” (music by Galt MacDermot, Lyrics by Joseph S. Lewis, and sung by George Tipton) isn’t subtle in letting you know what the bale of cotton symbolizes.

The tracking of the cotton throughout Harlem and its uses depending on the person is fundamental to undermining or enhancing the symbolism. Deke O’Malley isn’t the only person to use the cotton, he was first. Uncle Budd, a homeless man, finds it and sells it off to a junk dealer. The junk dealer sells it back to Uncle Budd. From there, it ends up at the community variety show in a burlesque routine. Then Uncle Budd takes it and moves to Ghana. The symbol of racism’s past is taken by a homeless black man and then used by a working-class black woman for burlesque. The reframing of this symbol into a commodity for lower-class black people to pass around is powerful. This reversal is crucial, and the secret to why Cotton Comes To Harlem is so satisfying. This is simple and weaves perfectly into the story: unlike using a complicated black performer like what Watermelon Man did with Mantan Moreland, Cotton chose a more direct and simplified symbol. Both are effective in their films.

The relationship between the police and the black community is fraught, to be concise. The Harlem Detective series is great but there is a strange vibe from the heroes being black cops. It’s reductive to say “ACAB” and call this specific film and book series copaganda. The series portrays the police force as something to be feared and run by people with violent tendencies, as well as an entity to be mocked and belittled. They actively worked with O’Malley and got in Coffin Ed and Gravedigger’s way. Cotton maintains this attitude enough, as the grit and gruffness of the books are subdued but not entirely. Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones are still violent and not above playing dirty to solve a case. They’re assigned to the black neighborhoods for obvious reasons. The attitude of the department towards Coffin and Gravedigger is reluctant acceptance; they are cops but they are the token black cops. It’s not okay to actively be too openly racist towards them, but go ahead just enough so they know their place in the ranks.

Released on the same day as Cotton Comes to Harlem was the caustic racial satire, Watermelon Man. Unlike Cotton, Godfrey had no prior connections with anyone directly involved in Watermelon. American maverick Melvin Van Peebles and author Herman Raucher were behind it. Van Peebles is a legend in his right but this was before his climatic fever pitch of a hit, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971). He had just come off of his debut (and arguably best) film, The Story of a Three-Day Pass (1968).

Watermelon Man is a jar of acid thrown in your face. It begins as a family sitcom of the era a la The Dick Van Dyke Show and The Brady Bunch. Van Peebles made the anti-Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner. The dad, Jeff Gerber (Cambridge in whiteface), is an unabashed bigot. The studio wanted Alan Arkin in blackface but Van Peebles made the right move. When the worst thing that could possibly happen to this character happened, he wakes up one morning as a black man. The first time he leaves his home as black he’s accused of stealing by cops, his liberal-minded wife can’t deal with having a black husband, and everything else from there collapses around him as he rebuilds his life as a black man in the US. This movie works because it’s ugly and blunt when dealing with racial issues. It is over-the-top, but it needs to be over-the-top to succeed in its grotesque approach (Bakshi’s Coonskin follows the same formula). It does that while never feeling preachy or like the faux inspirational bullshit Hollywood likes to chug out.

Of the many things that make Watermelon Man truly special, it can be boiled down to one performer, Mantan Moreland. He was active in the era when the “massa” type and other humiliating roles were the only things Hollywood offered black actors. For this reason, his legacy is complex; he had limited options to pick from, and wanted to work. The easy road is to blame him for this, but that’s the wrong tactic. Plenty of black and non-white actors’ roles were limited and stereotypical then, and still now, but not nearly as bad as it was. Mantan was asked to not participate in Civil Rights activities in the 1950s because of his history of playing submissive racist roles. On a surface-level public image, the logic is clear. However, the people in those positions are still aware.

Mantan plays the counterman at the local diner. He ignored Jeff Gerber when he was just another white bigot. Once Jeff returns as a black man with a higher-up job in a white office, Mantan has a change of heart. The casual disdain goes away and is replaced with real adoration. Inadvertently, Jeff is an aspirational figure: if you see it, you can be it. Mantan was picked for this role for a reason. This movie is directed by Melvin Van Peebles, a black man. This Mantan scene is short but its impact is undeniable: the bullshit will never totally go away, but the younger generation will have more opportunities and less bullshit to deal with.

Jeff Gerber’s transformation from a white racist to a black man pushed him into that token role in multiple aspects. His reputation at his job at the life insurance company goes from annoying loudmouth to the sole black guy who’s an annoying loudmouth. He loses his status and clients after becoming black. However, he then picks up black clients because he’s black now. This is a lazy business tactic but it leads to a positive outcome. Jeff starts to see the humanity in black lives after selling them life insurance policies. It’s not subtle. This sense of humanity he now understands is particularly true in the interracial sex scene. Once Jeff’s black, the office Norwegian woman wants him badly. They sleep together, but Jeff realizes it was her fetish. His humanity doesn’t matter, only his skin tone. After becoming targeted and tokenized by his white neighbors, he doubles their MOVE OUT offer of $50,000 to $100,000. With it, he starts his own life insurance company that serves the black community. The majority of Watermelon Man is the nightmare reality of being black in white spaces, of being just a body to use for others’ needs. By the end, Jeff refuses to be the token and discovers dignity within himself. The Jeff Gerber performance is astounding. Even though it’s grating for long stretches, it never crosses over into too much.

These films walk in very different but corresponding lanes. They tackle the aspects of then-modern black life that still echo now: dealing with the police, what it means to be American, being black in white spaces, opposing political ideals, legacies of racism, and more things that are seemingly never-ending. It’s an ugly truth especially in the US, that you carry your racial history with you at all times. This has countless aftereffects and implications that are psychically overwhelming, but manageable. The ideals of Black is Beautiful and Black Power movements are central to these. There’s an overlap between these movements. The core ideas are the same, even though the details are different: embracing your own blackness in all its forms. These are “message” movies, but they’re not homework movies.

Godfrey Cambridge was an immensely talented performer. He was picky with roles. The overarching ideas and themes of Cotton and Watermelon are the kinds of art that he wanted to make. The Hollywood system was not producing films like these, but Melvin Van Peebles and Ossie Davis both gave Cambridge the opportunity to flex his skills. The characters of Gravedigger Jones (Cotton) and Jeff Gerber (Watermelon) truly gave him room to show off his incredible skills. It’s notable that when working with black directors, he got real characters to work with instead of a one-off or minor support role. Both characters are complicated and grating (to various degrees), but exist with a genuine charisma that only someone like Cambridge can make tolerable and even likable. A lesser actor couldn’t personify the humanity of these complicated characters so completely. On paper, Watermelon Man sounds like a slog to dredge through, but the Jeff Gerber performance is next-level. It’s a tight-wire act on which the whole movie hinges. Cotton Comes To Harlem did not give as deep as a role, but Gravedigger Jones did let Cambridge play a more traditionally likable character in a more standard studio film. This proved he could easily carry both a mainstream film and a dark satire.

These are the only films Cambridge was given the room to really prove how talented he was on the largest scale. The roles that followed were not as deep or were just a scene or two at the most (Friday Foster [1975] being the pinnacle of this). Ending up with the roles that he got could have been the result of him being perceived as uppity and not willing to play along. It’s clear that he wouldn’t fit into the blaxploitation wave, nor that he would have much interest in doing so. It’s foolish to ask where the good roles were, as Cleavon Little’s career had a similar trajectory. Cambridge’s last role (but not the last one released) was in the TV movie, Victory at Entebbe (1976). Cambridge was playing Idi Amin but suffered a fatal heart attack on November 29, 1976. The role was taken over by Julius Harris. The next year, Cambridge’s final film was released posthumously with him playing Tom Turpin in the Billy Dee Williams joint Scott Joplin (1977).

Major studios at this point were about to shift into the blaxploitation wave. Gordon Parks had broken through in 1969 to become the first black filmmaker to direct for a major studio with The Learning Tree. Melvin Van Peebles, Bill Gunn, and Ossie Davis all followed suit to various degrees before the intense but ultimately short blaxploitation wave had taken over. Cotton and Watermelon are the kinds of major studio-backed black stories that blaxploitation pushed out altering the landscape. May 27, 1970, was a landmark moment for Godfrey Cambridge that should have led to a larger career. Cotton Comes To Harlem and Watermelon Man are special films that stick out among the black cinema that emerged at the time. They are still relevant and will remain that way for a long time.

Godfrey Cambridge’s life and career were cut short. In that small window, he left behind a multi-faceted career. He could do it all but was rarely given a chance to fully embrace everything he could do. Despite the cultural and professional obstacles, he carved out a unique niche embracing his blackness unabashedly through his artistic projects and Civil Rights activism (he appeared on William F. Buckley’s show Firing Line in 1968 and politely held his own). It’s a cliche to say, “There will never be another [blank].” Sometimes, cliches are true. Godfrey Cambridge could have conquered the world. At least, on May 27, 1970, he was king for a day. ★