PUMP UP THE COLUMN EXPLORES THE MANY INTERPRETATIONS OF PUNK AESTHETIC USED IN CINEMA

Genre film – in particular, horror – and punk rock have enjoyed a long and comfortable kinship. For bands like The Misfits and The Cramps, the connection’s explicit; but in broad strokes, you can find much of the same sort of spirit and values in each. Both are fields with low budgets and lower barriers to entry, where raw energy and inexpert passion win out over technical polish. Both are stripped-down art forms that eschew artsy meandering in favor of primal aesthetic thrills. Both target audiences are populist anti-snobs who celebrate low culture and questionable taste. Both are proudly intertextual, wearing their influences on their sleeves, deeply engaged in profound conversation with themselves. And let’s not forget that both horror and punk music have been on the front lines of the fiercest free-speech battles of modern times.

It may seem strange to think of film censorship in an era where anyone can log onto Youtube and casually watch some scenes from The Dentist, but it continues to be a reality all around the world. China famously censors or outright bans foreign movies for offenses ranging from homosexuality to ghosts to Winnie the Pooh. Many Islamic countries still censor movies on religious grounds. And surprisingly, Sweden, a country with a reputation for openness, tolerance, and cosmopolitanism, still operated a state censorship bureau until fairly recently. The Statens Biografbyrå, or State Cinema Bureau, formed in 1911, the world’s first film censorship office, and lasted a full century before officially closing its doors in 2011 (though in fact it hadn’t cut any movies since Martin Scorsese’s Casino in 1995, and hadn’t banned any in even longer).

Both punk rock and horror cinema have suffered under the yoke of censorship, and still do so today to a smaller extent – and for nearly identical reasons. They are fundamentally transgressive disciplines which aim to breach taboo and arouse primal impulses. Proudly trashy, largely unconcerned with any manner of elevated mental or spiritual experience, the punk song and the horror movie ground themselves in banal corporeal realities: fighting, screwing, bleeding, shitting, lusting, drugging, oozing fluids, breaking bodies. They portray hatred, and desire, and disgust, in clearer terms than is allowed in polite society.

This willingness to play in its own filth, to cross boundaries, to push subversive ideas not through reasoned argument but by rudely rubbing the viewer’s nose in the dirt, put both punk and horror squarely inside the crosshairs of the moralists who fear the influence of such libidinal forces on the social fabric. And with small budgets, insular and marginalized fanbases, and poor critical reputation, neither has traditionally been in much of a position to defend themselves.

One of the main motivations behind the censorship of groups like the Statens Biografbyra is in the interest of “public health” or “moral hygiene.” Violent content is likened to a drug, which a smart and responsible person may be able to use sparingly to no ill effects, but the average person is likely to binge until addiction sets in and causes profound and permanent damage to the psyche. And if you think of it this way, it makes perfect sense for the state to have an interest in limiting violent media – just as we have a public health department to keep citizens from dying from communicable disease, so should we have an agency to limit media that might fill some of our more impressionable citizens with murderous impulses.

But of course, the health department has whole labs and special equipment that lets them work with virulent microbes with minimal risk. There is, however, no way to figure out what parts of a movie are unacceptable without watching it. Exposing yourself. Who exactly is to be trusted with this task? Is there anybody around with moral character so strong that they can watch this horrid stuff without being affected? Or would even the most upstanding of citizens eventually be driven insane by prolonged exposure?

This is the premise of Evil Ed, a 1995 horror satire directed by Anders Jacobssen and written by Jacobssen and Göran Lundström, which skewers this view of movie violence as a public health risk. As the two men noted in a TV interview promoting Evil Ed, if violent imagery really inspired violent behavior in the viewer, then logically the people most at risk would be the censors and editors themselves, who after all have to look at this stuff day after day after day. A simple premise, but all the more effective for that.

The movie opens on a film editor going crazy inside his booth, stabbing at the film with his scissors, cursing wildly and making feral animal noises. His boss, a hefty man in a ponytail, knocks angrily on the door and threatens him to knock it off. He finally manages to break in just as the man sticks a grenade in his mouth and pulls the pin. His face completely spattered by a red mist of blood, the boss wipes off his glasses, points his finger accusingly, and says “you’re fired!”

The boss is Sam Campbell, and he heads up a department of a film distributor affectionately known as Splatter & Gore Department. The man who just lost his head was one of his editors, working on the Swedish cut of an insanely violent slasher franchise called Loose Limbs. Sam’s on a strict deadline to edit Loose Limbs, so he calls over to another department and requisitions a new editor, Edward, who usually edits artsy Swedish drama films. He tells Edward about the job and offers him the use of a small house outside of town so he can work uninterrupted.

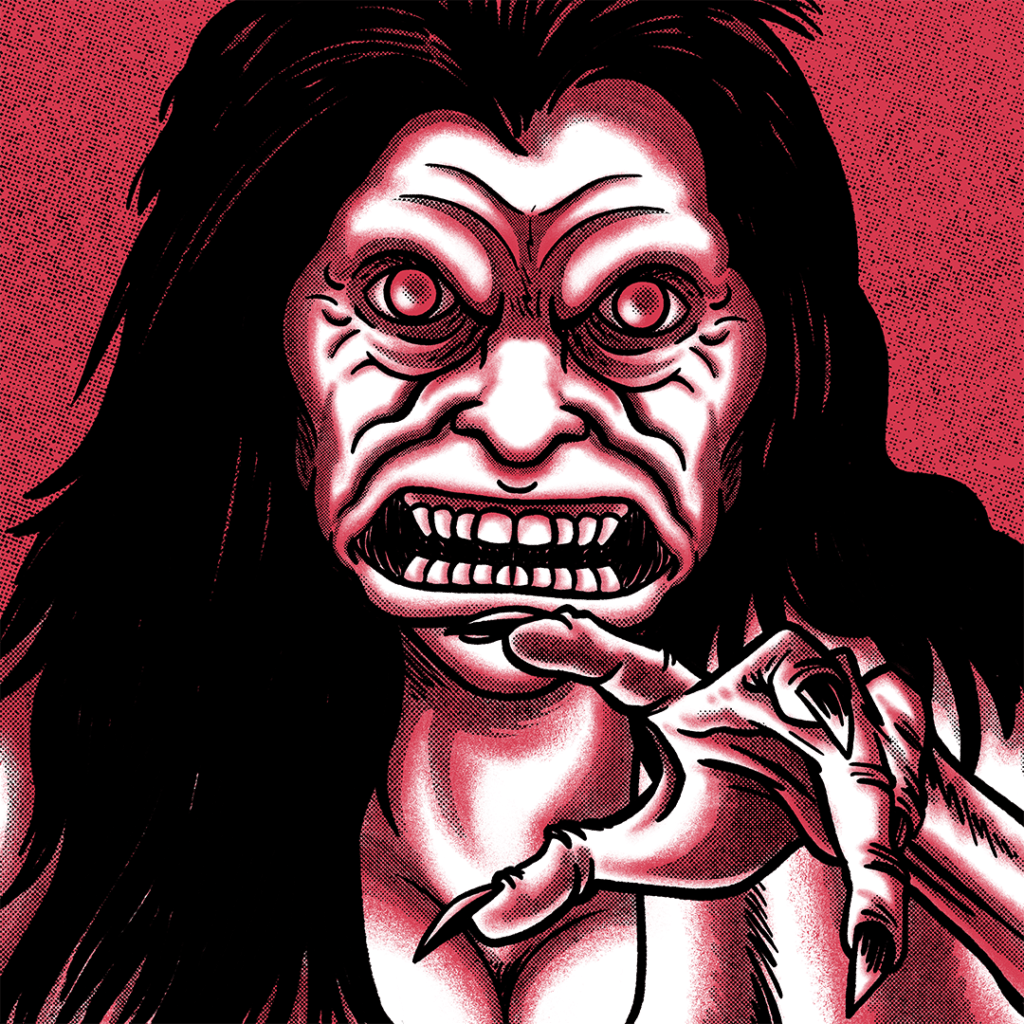

Ed is a clean, pleasant, fastidious man, and he has nothing but contempt for the prurient films the Splatter & Gore Department puts out, but his professionalism gets the better of him and he agrees. He stays at the house for days, working long hours late into the night, watching the stringy-haired psycho in the Loose Limbs series carve up hookers and hack off women’s feet with cleavers. His wife tries to be understanding, but after asking about his work (“in this scene I’ve been working on, a woman gets raped by a beaver and then shot in the face with a bazooka”) she becomes utterly repulsed and avoids conversation. As he descends further and further into the Loose Limbs project, he begins suffering terrifying hallucinations of severed limbs, zombies, demons, and gremlin-like creatures in his fridge, and he is visited by the ghost of the old editor, who tells him the world is irredeemably corrupt and he needs to “cleanse” it.

The film wears its influences on its sleeve. The title’s reference to the Evil Dead series speaks for itself, as do the name “Sam Campbell” and the zombie-like creature whose makeup design pays homage to the Deadites. Other movies in the horror canon get their own callbacks, in the form of individual lines (“they’re coming to get you, Barbara!” a psychotic Ed screams at his wife), production design (a creature in the fridge is an off-brand Gremlin) and the many movie posters for movies such as The Fly, Creepshow, Cape Fear, and of course, Evil Dead 2. As a director, Jacobsson evokes the campy spirit of his obvious idol with lots of Raimian close-ups and quick zooms. As a writer, he stuffs the script with quotable, over-the-top dialogue and absurd B-movie wackiness.

The spirit of punk rock in Evil Ed doesn’t just emerge from its anti-censorship themes, but from the look and feel of specific scenes which feel a lot like music videos. The use of strong angles, close-ups, and shaky-cams brings a definite MTV feel to the whole thing. The costumes and splashy sets evoke a campy, exaggerated take on button-down domesticity reminiscent of a Ramones video.

The most evident punk touch, however, comes in the character of Nick, a slacker with a girlfriend too hot for him, who performs various intern duties in the Splatter & Gore Department, slacking off whenever possible to watch the latest Loose Limbs movies in the screening room. His boss hounds him day and night. Ed insults his depraved taste and poor morals. Nick is a young, working-class, crude but good-hearted type, the kind of guy celebrated in a million punk anthems. And despite the supposedly corrosive influence of the splatter movies he obsessively watches, in the end he’s the most well-adjusted character in the movie. He’s the mirror image of Ed, whose meek, reserved exterior hides the mind of a monster, driven to punish and control.

The tipping point of Ed’s descent into insanity occurs when Sam drives by the house to check up on his work. Ever to the point, Sam asks “Where the fuck is my beaver rape scene?” Ed protests that he took it out because it was morally revolting, but Sam insists that the scene was OK as far as the censors were concerned, because there wasn’t any sexually explicit material in it. “No tits, no cock, no pussy,” he says. “Read my lips – not X rated! The scene stays in.” A demonic figure then appears to Ed and encourages him to kill Sam, which he finally does, dramatically starting the epic killing spree that will consume the remainder of the movie.

The twist here is that not all kinds of depravity are created equal. The fact that the studio even has to make a Swedish cut of the Loose Limbs series proves that attitudes regarding what is acceptable to show in a movie aren’t based on anything objective. They’re culturally bound, subjective – in a word, arbitrary. And as we’ve seen over and over in the history of censorship, our culture tends to regard nude bodies and explicit sex as more potentially damaging to the psyche than violence. Tellingly, this logic extends to sexualized violence as well – the censors Sam represents say that the candid depiction of rape, one of the most horrifying things humans can do to one another, is acceptable long as no one sees anything truly scarring like a naked butt. These topsy-turvy priorities are the product of cultural bias, perpetuated by the systematic censorship of works of art that might challenge them.

The standards of acceptable content are more or less completely arbitrary, but the manner in which these standards are applied is just as arbitrary. As Swedish journalist Gunnar Bolin notes, the Statens Biografbyrå routinely censored low-budget slashers with relatively little fuss, but fierce debate would break out when it censored a film that was considered to have artistic merit – for example, the movie 491, an artsy prestige drama based on a Swedish novel, from which the board cut a scene of (implied) bestiality. We tend to be more forgiving of explicit content in a movie we consider to have some “message,” some redeeming social or moral value. We feel compelled to distinguish between a “serious” film which needs to use explicit content to fulfill its artistic vision, and frivolous films that just want to shock and titillate.

The problem is, the question of a movie’s artistic legitimacy is even more subjective than the moral rectitude of its content. Just look at the many movies banned by Statens Biografbyrå which are considered classics today: including Nosferatu, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Psycho, and Mad Max. Knowing that critical consensus is so mutable, who would ever trust it to give someone else the power to decide for others what movies are credible enough to “deserve” a nasty murder scene. Why shouldn’t a movie like Evil Ed make the cut? It’s got a message too. It’s really about something, it wants to make a point, and if it couldn’t portray graphic violence, it wouldn’t make its point as well. Why the double standard?

The argument Evil Ed makes is a political one – it’s criticizing specific policies of the Swedish government. This is something else it has in common with punk rock, which has been intensely political ever since its early days, and which has frequently suffered politically motivated censorship. In the UK, the BBC banned subversive works by the Sex Pistols and the Clash; in the Iron Curtain countries, communist governments suppressed dissident punk scenes. Today in Russia, Putin throws punk rockers in jail for their supposed pernicious influence on public morals.

In both horror film and punk rock, the presence of explicit material often serves as a handy scapegoat when the real target of the censoring body is subversive political messages. It is certainly no coincidence that the punk bands that have faced the most legal trouble and institutional sanction for the supposed obscenity of their lyrics also have the most radical political content – Dead Kennedys, Bad Brains, Pussy Riot, the list goes on. Most people are generally in agreement that this kind of censorship is unacceptable in a democracy, whereas censorship on the sort of “public health” grounds we’ve discussed is more of a grey area. This is why censoring bodies in the Western world tend to take the latter approach. The ratings on movies, the “Parental Advisory” stickers on albums, are seen to serve a similarly benign purpose as the warnings on cigarettes or allergenic food (though as we know, these ratings can cause a movie or an album to lose distribution, which is just as effective as an outright ban).

But as I mentioned, the ways in which obscenity standards are applied is in itself a political decision. We’ve already seen how the decision to censor or not to censor often boils down to a judgment of artistic legitimacy. Just look at the target audiences of the media that falls on the bad side of the equation. The traditional consumers of “low” culture are young people, working class people, people with lower levels of education, people from historically marginalized communities. There’s a definite push to label their interests, the kinds of media that speak to them, as frivolous, artistically worthless, full of vile content that serves only to excite their worst impulses.

Think I’m exaggerating? Just look at a movie like Evil Ed. The movie portrays the act of censoring as driven by an essentially violent impulse. The scenes of Ed at his editing station, chopping up strips of film, use camera work and sound design to echo the brutal stabs and chops of the murderer onscreen, visually communicating the latent violent impulses slumbering within him. Ed’s button-down moralism masks a repressed lust to brutalize and dominate, needing only the right trigger to go ape. The rich boss is a venal, manipulative money grubber, who censors his movies for commercial purposes rather than through any real concern for his viewers. But Nick – young, dumb, crude, lazy, mind-warped from a million filmed murders – is an upstanding gent who rescues his girlfriend, kills Ed, and saves the day. Beyond the specific political points it makes, Evil Ed promotes a political worldview in which institutional powers fail and the unwashed masses (in the form of Nick) come out on top.

It’s genuinely subversive, but more than that — as they say — “punk AF.“