Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is long considered one of the horror genre’s grandest achievements, so much that in 1992, it was deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress. The level of talent that Universal Studios managed to corral for the 1960 feature is nothing short of perfect, speaking volumes about the film’s continued respect even 60 years after its release. At the top of that list is the slick, prestigious direction by the “dry wit Brit,” but there’s no discounting the shrieking chorus of violin strings courtesy of Bernard Hermann, the heavyweight thespianism of Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, Martin Balsam, and Anthony Perkins, and the shocking script by Joseph Stefano, who shifted Robert Bloch’s yellowed airport paperback into a tabloid piece of cinema exploitation.

Stefano’s script made the horrifying discovery of Norman Bates’ life (the tragic tale of a young man who has been murdering people in his decaying roadside motel, urged on by the demented ravings of his dead, decaying mother) come to life akin to the kind of sensational article seen sprawled across the cover of a National Enquirer bored housewives in Encino would flip their curlers about. Psycho starts out with a woman on the lam: Marion Crane, just having stolen $40,000 to pay off her lovers’ debts, then shifts to a murder mystery when she is abruptly killed. Filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson coined the term “gearshift movie” in reference to these types of features, a term describing a film that starts with one plot and later segues to another one entirely. From the moment of Marion’s murder, Psycho continues on its track now as a whodunit for the rest of its brisk 109 minute run time, with first time viewers truly believing that the mother the timid motel clerk Norman Bates keeps waxing nostalgic about really is committing heinous killings. But it’s not until the final act’s reveal that we see either Hitchcock or Stefano (or both) made one of the earliest examples of a slasher film — although certainly not realizing or intending to. The elements add up: there’s the killer Norman Bates, who was traumatized into the murder spree by his horrendous mother, dressing up in the visage of his madness. And, even though it’s rather small by definition of the sub-genre, we have a body count. After Hitchcock’s death in April of 1980, Universal Pictures began looking into what kind of money they could mine from the Psycho name, and then, from 1983 to 1990, made two theatrically released sequels and one made-for-TV sequel. Each sequel leaned largely into the film’s sub-genre of slasher film, bringing the hack and slash element of the ’80s to its forefront. Stealthily concealed within each individual film’s core is a sub-genre that amplifies Norman Bates’ escape from–and descent back into–madness to something more than just a cheap slasher cash-in.

The carnage candy on display in 1983’s Psycho II proves it is undoubtedly a timely product of the genre the film found itself in, as both the sex quotient and the gore quotient – especially in the vicious kills — are increased exponentially, doubling the body count from its predecessor. It’s fairly simple to sum up: upon release from a mental institution 22 years after the initial incidents, Norman returns to the Bates Motel (and the House on the Hill), and the murders pick up again. It’s a great template for a slasher film, and one that carries the renown of Alfred Hitchcock, even after his death. For a sequel that rolled down the pike 23 years later, Psycho II shouldn’t work, but it does because of the talents behind the camera: screenwriter Tom Holland spoke to Daily Grindhouse about his fears of following up on Hitchcock’s classic – “I was terrified. I was so sure that it was the end of my career. Because you just knew that every critic was going to attack you for having the hubris and the temerity to even attempt to do a sequel to Psycho. I don’t think I’ve ever worked this hard on a script, before or after.”

Filmmaker Richard Franklin partnered with Holland on this sequel; Franklin, who in addition to being a student of Hitchcock, cut his teeth on Ozploitation films like Road Games and Patrick. Franklin’s flourishes throughout the feature show that he learned well from his teacher; he handles the film with a glossy, shadowy flair, and the murder scenes are both blunt and brutal, giving the film an almost giallo-like elegance. Returning character Lila Loomis’s death (the knife stabbing directly through her mouth and out the back of her head) is a murder style one might see in Lucio Fulci’s The House by the Cemetery. And in the kind of cruel killing seen in the films of Dario Argento, Norman’s psychiatrist, Dr. Raymond, plummets down the stairs with a knife plunged into his chest, landing on the handle, resulting in the blade pushing into him even more deeply. The film uses silhouettes throughout, whether it be the glimpse of “Mother” right before she strikes the killing blow, glinting blade in hand (similar to the way many Italian whodunits use the killer’s hands clad in black gloves), or the mystery of whomever is creeping around Bates Manor’s back door. Whether friend or foe, the ghastly lighting gives all the nighttime scenes in the house a sickly pallor.

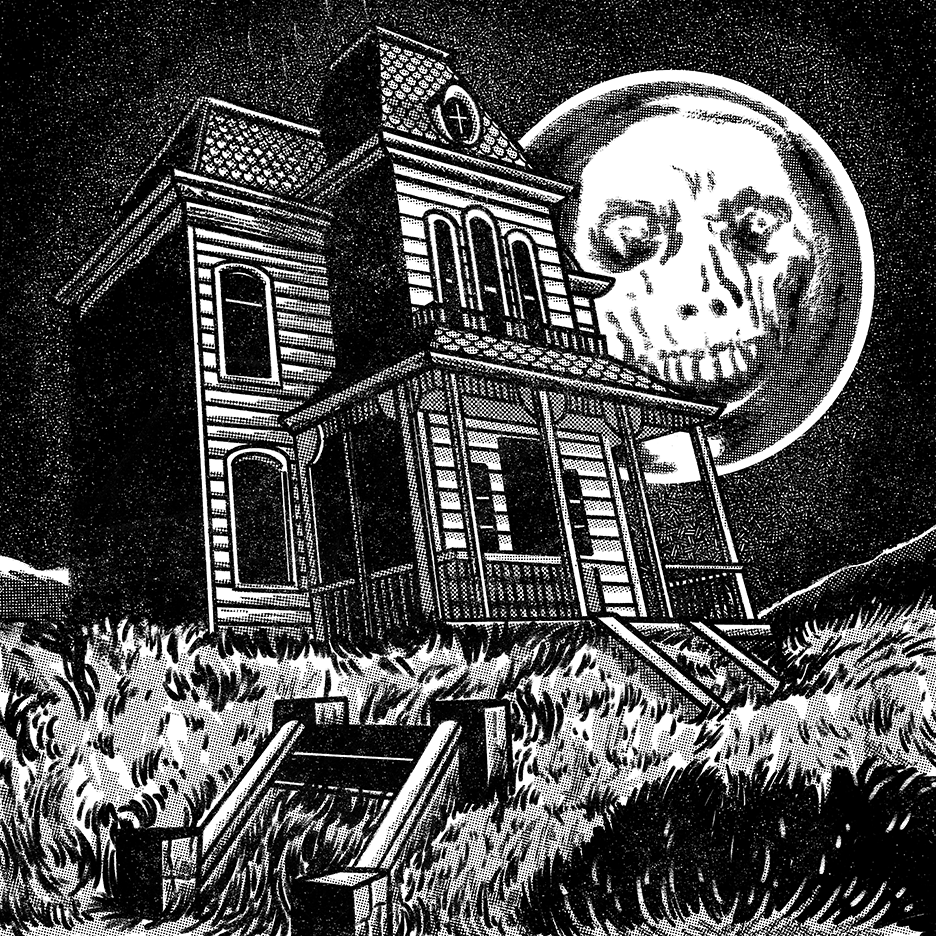

The other element people tend to overlook when discussing Psycho II is that it’s essentially a haunted house movie, and the ghost haunting the boy is himself. Over the opening credits and Jerry Goldsmith’s touching, spine-tingling score, the house is glimpsed – first in shadow of the night, then slowly in full color for the first time as the sun rises. The Bates Manor is waking up. From the moment Norman steps foot into the towering, monolithic Bates home, what was once a familiar domicile has now become alien and frightening. Cobwebs cling to the rafters, the nooks, and the crannies. The hinges on the front door groan. Sheets dress furniture that no one has sat in for over two decades. The toilets overflow with the blood of victims slain in its basement. The Bates Manor is unfamiliar to us just the same. We’re only given a few glimpses of the house in the first film, but here every single inch of the house is covered with the prowling camera.

The evening Norman stays in his home for the first time in two decades is the proverbial “dark and stormy night.” His mother’s murderous voice rattles both in his head and in the halls of his home (and sometimes outside the home), not unlike the way the moans of various poltergeist fester in walls with their malignancy. His mother’s room, once a place where he would truly become himself and his mother is now forbidden territory, lest the memories of his past float to the surface. Bates is a stuttering, shaky mess unable to even say the word “cutlery” without his dialogue skipping a beat, similar to the young and frightened protagonists of any typical spook house affair, all teeth-chattering and bone-rattling–something that is greatly aided by Anthony Perkins’ still youthful looks and voice.

Typically buried within the chemical makeup of a ghost story is a murder mystery, like in The Changeling where the key to stopping the malicious spirit is unlocking the secret of why it’s committing the haunting. In Norman’s case, he’s the reason for the haunting. The murders he committed in the home where he lay his head lay ruin on his mental state. He can never wash away the metaphorical bloodstains. How can he get rid of a ghost that he himself caused?

The other element a good haunted house movie must have is a phantasmal specter only detected by the protagonist–the ghost remains unseen by others who, therefore, don’t believe the protagonist–and Psycho II has that and then some. See, it’s one of the rare examples of a male being gas-lit in cinema. From the moment when Norman is released, he’s constantly hounded by a family member of one his victims, Lila, and she isn’t content on letting the courts let him get away scott-free. So she partners with her daughter Mary, and begins an attempt to crumble Norman’s fragile mind. The duo plant items like a sharp, clean butcher knife in a drawer of ancient utensils, make phone calls in his mother’s voice, redress Mother’s room like it was when she was alive, and even dress up like Mother in her wardrobe. All these things give Norman the feeling that he’s seeing her ghost, or maybe that she’s real. Their efforts are akin to the way one would wake up the spirits in a long-dormant mansion with a Ouija board or a Séance, though they end up snaring a different, but altogether malevolent being: Norman’s biological mother, Mrs. Spool (who is actually committing the killings seen throughout the feature). Both Mrs. Spool and Lila share similar thoughts about Norman, though they differ dramatically in their goals. One is seeking cruelty by tampering with his headspace; the other is seeking love by way of cruelty. One wants the embrace of maternal love; the other wants the embrace of a straight-jacket. In the end, neither one of the parties are right, and ultimately all this does is drive him to the brink. Once Lila, her daughter, and Mrs. Spool are dead, Norman re-assumes the maternal madness of Mrs. Bates, reversing the state-mandated psychiatric exorcism. In a manner, it’s a repossessing of himself, and a reverting of the spooky house back to the evil entity that will bring harm to anyone who crosses its threshold.

For 1986’s Psycho III, Perkins pulled double duty, stepping in front of and behind the camera to provide the cruelest of the franchise’s sequels. As an example, when we first see Norman, he’s poisoning birds so that he can have subjects for his taxidermy hobby. Charles Edward Pogue’s script wastes no time concealing Norman’s madness as he’s seen constantly conversing with Mother’s emaciated, rotting corpse or pretending that the psychotic phantom cutting up folks around the motel is anyone other than the young Master Bates. The inhumanity doesn’t just stop with the motel proprietor picking off little birdies, it keeps up with the savage killings Norman doles out. Though there are fewer here than in the previous film, the murders don’t let up on the viciousness – retaining the 1960’s film shattering of our false sense of security when showering. Getting stabbed repeatedly while boxed up inside a phone booth with our shirts covering our faces feels like a relatable fear, as well as getting our throats slashed while on the toilet because of the defenselessness we feel. We know it probably wouldn’t happen, but the fact that it could happen causes us to ensure that our bathroom door is locked tight during our next bio break.

The landscape of the Bates Motel and Manor has now become a dry oasis, the sun dappling down on the parched, sandy topography while dust storms, skeletal trees, and dead leaves billow around the eaves of the motel with tumbleweeds bouncing across the two-lane blacktop that stretches alongside it. All this imagery establishes Psycho III as “desert noir horror” by way of its locale and characters. There’s Jeff Fahey, who continues the trend he established as a thespian in the ’80s and ’90s – a sleazy, sweaty character actor — as Duke: a full-time drifter, part-time grifter who pulls a gig working as an assistant manager at the Bates Motel. There’s our cocky, headstrong cub reporter Tracy Venable, played by Roberta Maxwell, who works to uncover the mystery around the missing Mrs. Spool. Tracy is working hard to convince folks that Norman is back to his murderous ways, all while delivering some knockout lines in response to Duke’s lecherous male behavior: “You know, you really shouldn’t rely so much on that pretty face and those pearly whites ‘cause come-ons like that could get them both punched out.” And we have our damsel in distress, Maureen Coyle, played by Diana Scarwid, a former nun whose rejection of faith has led her to the Bates Motel. In the center of it all is Norman Bates, who would usually fill the noir role of gullible patsy (if we’re using the Blood Simple template, the Texas murder and money noir — a film which Perkins loved and utilized as inspiration for Psycho III, so much that he brought on the film’s composer, Carter Burwell to score the slayings). Norman is in the John Getz role, but unbeknownst to everyone swirling around him, he’s a psychopathic killer. Initially, Perkins even wanted to shoot Psycho III in black and white, which would’ve enhanced its position as a noir title, but found opposition to that. It would’ve have been stellar, considering the way he utilizes shadows in Mother’s bedroom when showing her corpse, giving the face an unknown, grisly mystery. There are plenty of gorgeous colors about in the scenes he stages: the aforementioned phone booth murder (where the reds of the blood and the blues of the sizzling neon Bates Motel sign complement each other, creating a gorgeously photographed murder), the scene where he discovers the body of the bathroom victim (his face painted in queasy green, further symbolizing his physical disgust at the crime he’s committed), and the scene with Duke and his hookup Red (envisioned with the sordid lens of a trashy, Skinemax feature).

The franchise’s requisite end of film plot spillage, as in, “this is what’s really going on with Norman,” is gussied up a bit as it takes place between our ostensible final girl, Tracy, and the bewigged Norman; Tracy doles out the truth behind his relationship with Mrs. Spool, and Norman doles out knife swipes. It’s quite a gorgeous scene, with the numerous candles lit striking severe shadows everywhere. Pogue’s revelation that Spool actually isn’t his mother, but kidnapped him as a young boy and raised him is a little too soap opera-ish. There’s also the melodrama of both the religious and secular “guilt film” genre buried in here as well. Maureen is constantly haunted by her past at the convent where she accidentally slays a nun in the film’s opening moments (which Perkins orchestrates in Hitchcockian style, aping Vertigo), and while attempting to commit suicide in the infamous Cabin One, she sees the murderous visage of Norman. But instead of him clothed in Mother’s wardrobe, she hallucinates that he’s the Virgin Mary holding a crucifix towards her. It’s her guilt that drives her to leave the convent, to attempt to take her life. In turn, Maureen sees rehabilitating Norman as a means to make up for her perceived sins against God; saving her life ultimately negates the lives he had previously taken.

Norman’s guilt over the murders he committed is spelled out in his monologue in the diner while chatting with Tracy: “My cure couldn’t cure the hurt I caused. My return to sanity didn’t return the dead. There’s no way to make up that loss. The past is never really past. It stays with me all the time. And no matter how hard I try, I can’t really escape.” Doting over Maureen becomes his way of escape, which, in his fragile, broken mindset, allows him to see her as a way of rehabilitating his violent crime against Marion Crane (who Maureen resembles) and the other bodies he fed to the swamp. His failure to save Maureen from his Mother’s mania (she plummets down the stairs and punctures her skull on the arrowhead of a Cupid statue) ultimately proves in breaking him free of his Mother’s mental imprisonment. The final shot is the only false note, because it works so hard to negate the cathartic mental weight he shirked loose by stabbing his “Mother’s” taxidermied corpse. The shot echoes the end of the first film (“why, she wouldn’t even harm a fly”), and is presumably there to send chills down the spines of audience members, but really reeks of studios dropping bait for a sequel.

That sequel, Psycho IV: The Beginning would roll out four years later in 1990, but this time skewing theatrical release for broadcast on the Showtime Network. It was penned by returning scribe Joseph Stefano, and largely ignored the events of the two sequels that preceded it. In this installment, Norman is rehabilitated to an extent, and there’s no mention of any of the soap opera antics with Mrs. Spool nor any of the additional murders that were committed in the ’80s. The film is pulling the “this is the real sequel to the original” gambit that 2018’s Halloween did — even tethering its tale to a modern form of media (Halloween has a podcast and Psycho IV: The Beginning has a talk show). The talk show is used as the gateway through which the majority of the film is framed: the backstory of why Norman Bates grew up with the psychopathic tendencies he did and how he’s struggling to suppress the murderous feelings in his present (Norman wants to murder his spouse and unborn child so as to sever the poisonous Bates line once and for all). The film thankfully ends with Norman finally achieving the peace of mind that we, the audience, thought he obtained at the end of Psycho III, courtesy of his wife, which makes the whole saga compelling in that a woman’s abuse turned him into the monster he was and a woman’s love rescues him becoming that monster again. Though on its surface, it’s easy to then see how Stefano and Mick Garris (essaying some crackerjack direction) run with the story, seeing it as a head-shrink procedural: a race against time to prevent a murder. But it’s also easy to tilt our heads and see it from another perspective: a 1950’s coming of age tale, though not one about sexual awakening, but about sexual repression.

The coming of age tales of the ’80s and ’90s were written with the nostalgic look back at a decade long before the film was made, usually either the ’50s or ’60s where the writers spent their formative years. Sometimes they were bittersweet dramas like Book of Love or The Nostradamus Kid, but more often than not they were easily marketable sex comedies, features like Porky’s or Mischief, that filled the multiplexes with their blend of sometimes offensive, off-color humor and hormone-addled meatheads looking to score with the women who populated the films. These sex comedies were clearly made with the male gaze, what with the copious amounts of skin on display in any of them. With Psycho IV: The Beginning, the male gaze of the coming of age tale is rather evident in the first murder we see Norman commit, post matricide. A beautiful young woman just appears of out of nowhere, dolled up like she’s a teenage dream spokesmodel for Coca-Cola, and proceeds to flirt with young Norman almost immediately. The playful vamping from the girl as she works to get Norman into bed, taking off her clothes, and yet he can’t bring himself to make love to her. One could chalk it up to the chasteness of both men and women in these types of motion pictures, but not here. It’s not a physical impotency that he’s faced with, but rather a mental one – his mother’s corpse urging him to kill this girl. And for this poor unfortunate woman, instead of walking into some hot-blooded Fourth of July sex-by-the-light-of-fireworks scene, she’s walked into the den of a murderer.

For a solid coming of age film, our male hero must be yearning for a girl next door, and here’s it’s the woman living in the House on the Hill: his mother. The movie explicitly dispels the notion that it’s an “incest tragedy,” as it isn’t really that Norman wants to sleep with his mother (even if he gets an awkward erection while snuggling with her in her bed), it’s about the unobtainable yearning that accompanies the pursuit of the male towards the female. It’s not anything new for the coming of age tale to be about the lust a young male has for an older woman; that’s why he chose an older woman to have a dalliance with before strangling her at his Mother’s urging. There are a few films that come to mind that take this to task: the 1960’s set feature, A Night in the Life of Jimmy Reardon, in which Ann Magnuson seduces River Phoenix and he sleeps with her, or Stephen King’s amusement park-set novel Joyride, in which our hero falls for and beds an older woman, and, like in Psycho IV: The Beginning, there’s a murderous bent to the proceedings around the main tale.

Consider that like most tales where the girl next door is our lead’s romantic endgame, sometimes she’s tethered to an obnoxious jock type, and in this film, that’s Norman’s mother’s fiancé, Chet. The scene in which they spar with boxing gloves is not too dissimilar to scenes where the hero tries to prove his physical worth to the object of his affection only to be emasculated in front of her. Here, as Norman looks up at her, she looks down at him with the same type of pity that often proceeds his eventual “win” in obtaining her love. The dark psychological bent, though, is that instead of his pursuit either ending in him winning the love of this girl next door or coming to terms with losing her love, he kills her and taxidermies her corpse so that he instead preserves her love, a place where she can no longer reject him or yell at him. Love stories in fiction and non-fiction shouldn’t end up like that, but for Norman, it’s only the beginning.

Given the way Hollywood has become a soulless slaughterhouse treating franchises like cows they can cut up, mangle, and sell to a consuming audience until there’s nothing left on the bone, it’s easy to be so cynical as to apply the same adage to the Psycho franchise. But that disillusioned filmgoer would be wrong. Universal Studios treated each sequel on its own merit, allowing each filmmaker to add their own spice to the stew and filter in their own cinematic tastes, giving the franchise an individuality that felt in the same canonical world, and at the same time never letting the saga grow stale. None of the sequels feel like we’re getting a different appropriation of the same old tale. After Gus Van Sant’s ill-advised remake of Psycho in 1998, Universal Studios made it apparent they were content to let sleeping dogs lie — save for the fairly solid television prequel, Bates Motel. Still, there’s something kind of comforting to know that out there in the streaming ether, there are three sequels to Psycho that manage to stand side by side with the more than reputable original and do something special with their entries.