“Cars suck,” the not-so-hidden message in the opening scene of Joseph Kahn’s 2004 action piece Torque, presents itself with cocksure bravado via a super-stylized spinning street sign. The sequence, a late addition to the movie, proved to be a good one: an adrenalized race between both four-wheeled and two-wheeled high-powered machines introduces us to what amounts to, at a glance, seemingly little more than an aggressive action movie about motorcycles and the people who ride them. But to the savvy viewer, Torque reveals itself as a film that parodies the hard muscle and macho attitude of a certain street racing film that came before it, so much that it transcends parody itself and enters its own realm of cool.

Action movies are often described as “absurd”; a generally agreeable statement, as action films tend to exist within the scope of “wildly unreasonable,” “illogical,” or “over-the-top.” Torque certainly lies within this description (Kahn has stated on one of the Blu-Ray commentaries that he wanted to make an “unrealistic biker movie…on purpose”), partly because the absurdism it presents is peppered with tongue-in-cheek and sarcastic humor. Action and comedy historically have played well with one another (just ask Vaudeville or any number of “buddy cop” movies from the last 40 years), but while comedy has found enduring value with examples throughout timeless beloved filmmaking and even classical literature, action as a genre has not enjoyed the same reverence among cultural scholars and commentators alike. Why?

One leans toward the highbrow/lowbrow argument. Many regard “lowbrow entertainment” such as action films as unsophisticated and possibly even vulgar. Although at times highbrow entertainment can take a cue from its lowbrow counterpart (one could argue the works of arthouse filmmakers like Peter Greenaway or Walerian Borowczyk may fall into this category), many cinephiles still have trouble seeing the merit when action movies employ similarly simple “vulgarities.” “Vulgarity is a very important ingredient in life…We all need a splash of bad taste,” former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland is famous for saying, and the fact that the snob-a-rama Criterion Collection includes entries from Paul Bartell and John Waters, let alone special editions of RoboCop and Armageddon from years back, should be enough evidence for us all.

But let’s get back to comedy. Parody, as a comedic virtue, often transforms the sublime into the ridiculous. In pure form, parody subverts what is expected and brings new meaning to the material. On a commentary track, one of the film crew points out that Torque is “a spaghetti western on motorcycles.” In that brilliant description, the film is a modern update of Western tropes, with ridiculous results (imagine if you will a fight between two opponents on horseback and they fight while riding the horses. And eventually, the horses join the fight as well while they’re being ridden. Now, replace the horses with motorcycles, and you literally have a scene from Torque starring Monet Mazur and Jaime Pressly.). So, when we lay out the bro-pleasing, soap opera seriousness of a story like The Fast and the Furious, a film like Torque comes along, sees that seriousness, and virtually says “to hell with it.” That casual use of parody is what gives Torque the upper hand on artistic expression because the heightened sense of self that comes with absurdity is enhanced by this humor. Plainly, The Fast and the Furious tells us action movies can be about something; Torque answers with “why should they?”

The Theatre of the Absurd…tends toward a radical devaluation of language, toward a poetry that is to emerge from the concrete and objectified images of the stage itself. The element of language still plays an important part in this conception, but what happens on the stage transcends, and often contradicts, the words spoken by the characters.

– Martin Esslin, The Theatre of the Absurd, 1961

Which leads us to a revelation perhaps even too sophisticated for those professed cultural sophisticates. When we get down to the basics, it seems no far stretch that many action films can very well exist in the same realm as the so-called “Theatre of the Absurd.” To refresh anyone’s memory, Theatre of the Absurd, with its roots in Existential philosophy, started as an experimental artistic movement in the mid-20th century more or less addressing the breakdown of life’s blandness leading into absurdity. Conceptually, Theatre of the Absurd can use broad comedy, tragic events, and elements of nonsensical language to parody realism. There comes a time when words fail to express the essence of human experience, when language can only scratch the surface of what pictures can communicate. Action movies, with their explosions, martial arts fights, fast cars, and helicopters, use their relentless eye candy to gain this edge. Torque uses everything just mentioned and more: it does so with the added advantage of sleek music video-style direction. Kahn’s vision of absurdity, i.e., his “unrealistic bike movie,” is expertly executed by his assemblage of stunt coordinators, performers, and second-unit wizardry. Edits are slick and chic (“geometric editing,” as the crew refers to crafty segments like how the opening credits move along the screen with the bikes’ movements), creative dolly zooms abound, and Kahn even throws in a few flashy knife-blade reflection shots reminiscent of mid-century European directors and their penchant for mirror work. Torque’s costume design aesthetic possesses more finesse than any Fast counterpart, too, sneakily throwing in nods to mod 1960s racing suits. And the loud, colorful, and ridiculously over-the-top rally scenes overflowing with bikini-clad babes, bikes, and beer more or less put to shame what The Fast and the Furious’s “Race Wars” was at all trying to achieve. Visual language lives in absurdity, lest it be dull and unimaginative; this is lyrical; this is poetry in motion.

Another criticism of the action genre is that the dialogue used is often dumbed down, or relies too heavily on one-liners (replay everything you’ve ever heard Arnold Schwarzenegger say in your head right now). If Theatre of the Absurd says language is meaningless, it’s likely because over time language becomes stereotyped and conventional. Often Theatre of the Absurd uses black humor to make this point; Torque is self-aware enough to parody this, too. Probably the most famous line ever spoken by Dominic Terretto in The Fast and the Furious is the one about him living his life “a quarter mile at a time,” a line that is supposed to indicate that Dom is reaching some sort of free-from-the-shackles-of-worry oblivion in the ten seconds it takes to drive two city blocks. Martin Henderson’s character Cary Ford, Torque’s protagonist, repeats the line word-for-word when his gang of motorcycle-riding pals takes a break from the heat inside their cave hideout, to which girlfriend Shane (Monet Mazur) replies, “That is the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard.” That exchange, actually improvised by the actors, is satire for the sole purpose of ridicule, encouraging an everyday audience to go beyond convention.

Action movies have more in common with Theatre of the Absurd than just turning up their noses to language. As mentioned before, the highbrow/lowbrow argument can extend to Theatre of the Absurd. Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett’s poster child for the movement, opened to audience after audience of bewildered European sophisticates only to finally enjoy a perhaps surprisingly warm reception when performed for the convicts at San Quentin State Prison in 1957. Similar to modern action films, the unsophistication of the prison audience is likely what helped them understand and appreciate the play more: any expectations or preconceived notions about the material could not have possibly been influenced by the “intellectual snobbery” (as Martin Esslin also writes) of much of the play’s regular audience. So it’s not really that an audience has to be “dumb” to enjoy action films, it’s that the audience needs to let go of pretense.

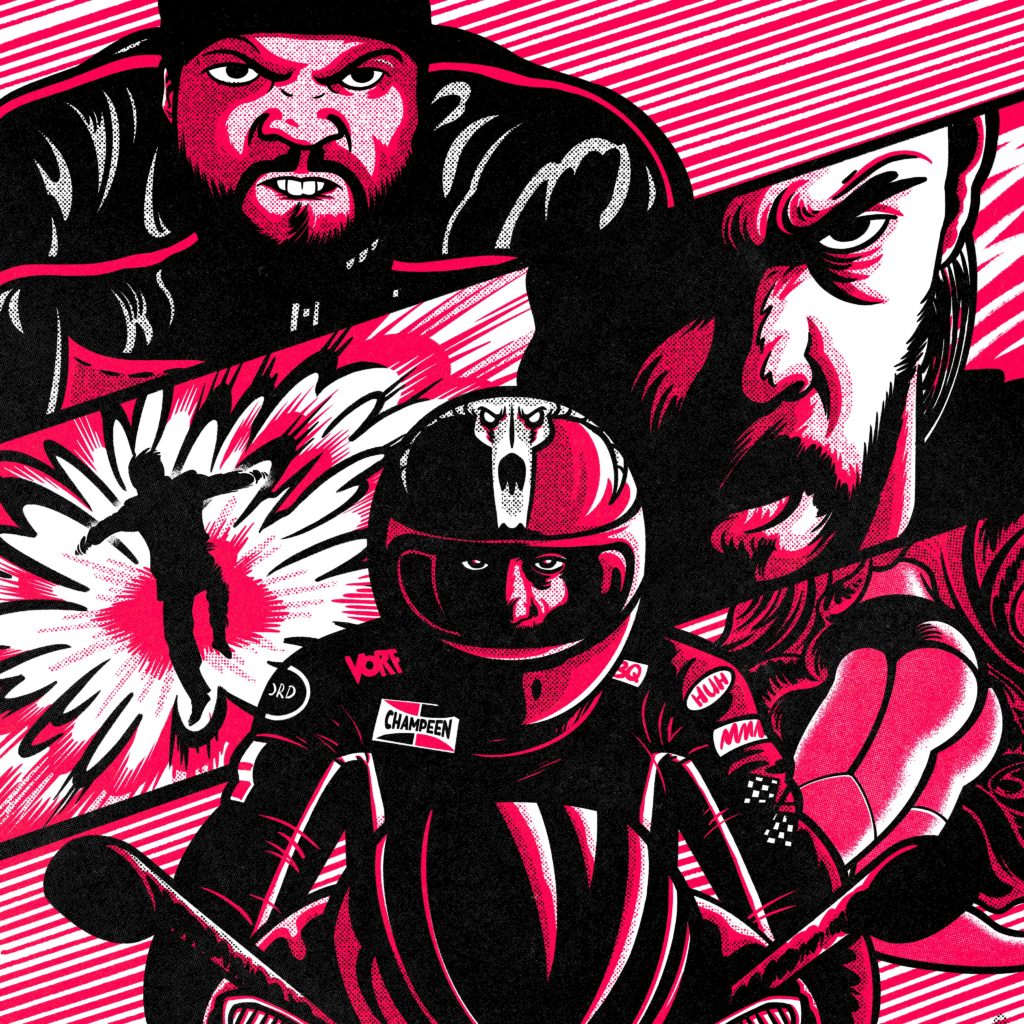

And so, while many still consider action films “big and dumb,” there are plenty of others who are able to enjoy them through the lens of escapist cinema. We don’t necessarily have to think about lockdown or our stimulus checks or affordable child care or any number of real life worries while we watch action movies. For a couple of hours, we can revel in a freedom from responsibility and logic and just have our toys. And honestly, that’s all movies like Torque and The Fast and the Furious really are: a metaphor for Tonka Trucks and Matchbox Cars and other “toys for boys” (or whomever else), wherein the characters are audience surrogates who get to play with the cars and bikes and whatnot in ways we never actually could. Cary Ford and Dom Terretto are beautiful, manly, idealized action figures poised and ready for our amusement. And, cheekily, we can feel okay about objectifying them because Theatre of the Absurd says objects are more important than words.

Finally, Torque’s use of parody doesn’t just extend to The Fast and the Furious. Within the first act, we see comical references to “serious” movies like Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove with “HI THERE!” written on the bottom of one of the biker’s boots, and a keen-eyed cameo from the tanker truck featured in Steven Spielberg’s Duel. But what makes Torque unknowingly meta–at least at the time–is that in parodying The Fast and the Furious in 2004, it predicted what the Fast franchise would become. Joseph Kahn once noted, “I didn’t want realistic fights, I wanted things that look pretty,” which demonstrates perfectly what happened down the road (pardon the pun) for that particular set of movies featuring stunt drivers commanding vehicles not only racing down the streets of Los Angeles, but eventually flying outrageously through the air. Consider that good or bad, depending on your movie-going tastes, but through comedy and a distinct vision, Torque acted as a mid-2000s harbinger for fashionably-made, high-octane action soon to come, and even with its ridiculous presentation, is ironically a lot more focused than the longwinded epic grandstanding style of other actioners of the period. In its absolute absurdity, Torque snidely tells all the snobby haters that action films can have depth, and still not really need to mean much of anything. ★

Thank you for joining us for Action Week! ICYMI click here for yesterday’s entry on the cultural fusion of Rumble in the Bronx!

What’s the deal with Action Week? Find out! And be sure to keep your eyes peeled for more great stuff in our column Into Action!