WEIRD BONERS IS DEDICATED TO ALL THE WEIRD WAYS FILMS AFFECT US SPIRITUALLY, INTELLECTUALLY, AND OF COURSE, PSYCHO-SEXUALLY

Biopics are a strong contender for the worst sub-genre. They’re where bad filmmaking is not only allowed, but rewarded. From cheesy melodrama to the type of humor only a stuffy relative laughs at, biopics rarely have anything good to offer.

Occasionally a biopic comes along that isn’t a nauseating fluff piece. Last year I was quite taken with Judy, a film I saw three times in theaters. Biopics have more going for them when they focus on a darker moment in an icon’s life like that one does. While looking back on Judy Garland’s drug-fueled childhood, it focuses on the final year of her life when she was considered by Hollywood too hostile to work with. A notable sign of how dire things were was when she was fired from the film adaptation of Valley of the Dolls, a bestseller inspired by Garland’s demons.

The two films I’m going to talk about prove how compelling dark biopics are. Both films dive into maddening perversion. Both show iconic performers in an unsavory light. Most importantly, both films depict high profile perverts having penile implants.

I think I speak for everyone when I say any distasteful rumor pulled out of Scotty Bowers’ book Full Service is more memorable than any moment pulled from the life of Steve Jobs (Editor’s Note: let’s not forget there have been three biopics made about Steve Jobs, if we count Pirates of Silicon Valley). If the same sub-genre that holds up two bores like Green Book and Molly’s Game can also be capable of two quality films revolving around lustful lunacy, it means any sub-genre has the ability to be great.

Maybe hogan ain’t so much a hero

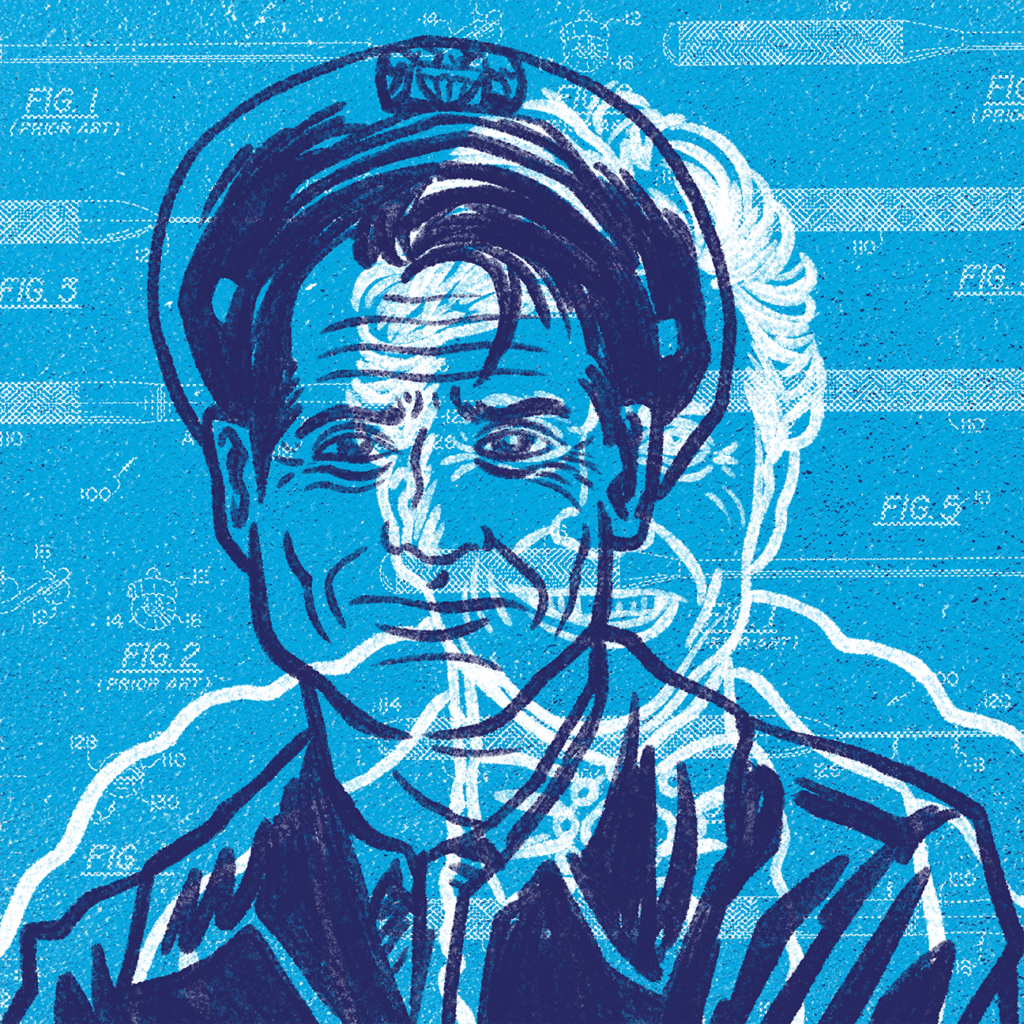

The first film, Auto Focus, explores arguably the most compelling Hollywood urban legend involving Hogan’s Heroes star Bob Crane’s obsession with documenting his one night stands with then-state-of-the-art home video recording equipment. It’s all the more compelling with how this story concludes with a decades-long unsolved murder.

Paul Schrader directs this film, and it’s exciting how such a unique filmmaker dedicated a portion of his life making a movie about the sexual depravity of Bob Crane.

One of many things this film gets right is how absurd the concept of Hogan’s Heroes is. This comedic sitcom about Allied soldiers in a Nazi POW camp premiered 20 years after the conclusion of World War II. Too soon? The Twilight Zone‘s Rod Serling certainly thought so. During her episode of Gilbert Gottfried’s Amazing Colossal Podcast, Anne Serling mentioned her father’s boiling hatred for the way a sitcom had the audacity to depict Nazis as comedic simpletons.

Auto Focus begins in 1964 just before Crane began starring in Hogan’s Heroes. He’s a squeaky clean radio DJ who abides by what society expects of him. While still resembling the stern and conservative ’50s, 1964 was a year testing the possibilities of sexual liberation. Playboy had by then been in existence for ten years, and the trendy Playboy Clubs had been in operation for almost five years. As he politely walks through a suburban existence where he and his family live in a home ideal for a sitcom, Bob Crane also has this duality of being a jazz drummer playing in nightclubs with topless dancers.

We also get to see the slick and stylized Playboy influence when we enter John Carpenter’s (not that one) house. It’s the ultimate bachelor pad with a wide variety of vinyl to choose from, and even a slot machine. This suave interior, along with Crane’s family home and the cars that pass by during the first half of this film, is Grade A nostalgia porn. Auto Focus captures a viewpoint of the early 1960s held up by people who think it was all homemade milkshakes and great tunes on a jukebox.

You get to see the trappings of conformity when Crane’s wife finds gentlemen magazines in their garage. In a type of shaming we forget existed in a pre-Pornhub world, she brings up the possibility of confronting their priest about it. After landing the lead role on Hogan’s Heroes, Crane meets with his priest in a diner because he’s concerned about Crane missing Sunday service. Those scenes capture how dominant Christian purity still was in the mid-1960s when such conversations happen in Los Angeles and not just small towns with one streetlight.

Auto Focus details the culture shift happening throughout Bob Crane’s short life and how the change was too much for a repressed man. Like an alarming amount of people, Crane seems to have married his high school sweetheart thinking that serious commitment would cancel out any impure thoughts. For fifteen years it worked, then Crane meets John Carpenter. This loser sees his ticket for relevancy, latches on, and helps Crane embrace his demons.

In the beginning, Crane thrives in the type of cocktail party seduction depicted within the pages of Playboy. Then, like any addiction, it becomes too much. A constant within this story is how giddily Bob Crane shared his Polaroid scrapbooks with people, completely unaware his co-workers didn’t want to see a grainy photo of Colonel Hogan getting a blowjob. It says a lot when Hollywood finds your perverse lifestyle to be excessive.

The scenes that detail Crane’s down and out existence in the 1970s are fascinating. One example has Crane telling a bartender to put on Hogan’s Heroes so a couple of women will recognize him. Another memorable moment is Crane participating in one of the few jobs willing to hire him, a celebrity cooking show, which he inevitably ruins by rambling about how hot a busty audience member is.

Throughout these ’70s scenes, Crane is in a leisure suit and wearing aviator sunglasses. The same guy who looked like the quintessential American male in 1964 now resembles a gross-out Drew Friedman/Robert Crumb illustration where the character glistens with sour sweat while sporting a morbid grin. There’s a great scene in which Crane and Carpenter are sitting in a basement quietly masturbating to a reel of Crane’s hotel romps that feels like a tragic moment from Boogie Nights. With his facial features, Greg Kinnear was the most ideal actor to portray Bob Crane, and he lives up to the expectations of dream casting by capturing how you can lose yourself in sex like any other addiction.

Even while collecting a vast amount of one night stands (which is cool if you subscribe to the philosophy of Gene Simmons), Auto Focus documents how depraved and dark it can get. Paul Schrader successfully exhibits his talent by taking celebrity gossip and using it for a compelling journey of a once repressed man fully giving in to his desires and somehow finding a way to make others uncomfortable during a carefree sexual revolution.

liberace SAYS “BOY BYE” TO his “baby Boy”

The other half of this double feature is Steven Soderbergh’s Behind the Candelabra, one of the most rewatchable films from the last decade. It’s based on the tell-all memoir written by Liberace’s former lover, Scott Thorson. As someone who’s read it, I can tell you this film oddly enough is one of the most accurate of book-to-film adaptations. Practically every scene and line of dialogue is found in the book.

Its rewatchability stems from having one of the greatest casts ever assembled: front and center is Michael Douglas playing Liberace. With characters like Gordon Gekko in Wall Street as well as a man having sex with both Jeanne Triplehorn and Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, Michael Douglas defined what it meant to be a man’s man in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Gordon Gekko was supposed to be this repulsive representation of greed, but turns out every guy wanted to be him. While watching Wall Street, I’m surprised Oliver Stone failed to realize millions of dudes would idolize a guy quoting The Art of War in the middle of a locker room.

That legacy of machismo makes Douglas’s dedication to playing the iconic flamboyant showman all the more impressive. It says a lot when an actor can successfully portray someone overloaded with testosterone like Gordon Gekko and a camp icon who refers to his male spouse as “baby boy.” Along with the dialogue, he’s consistently making out with Matt Damon, and in one scene, taking poppers while being anally penetrated. Michael Douglas might be the most daring actor who became an icon through alpha roles. It’d be like watching John Wayne have Robert Redford straddle his lap while referring to him as his “naughty little pilgrim.”

Douglas’s Liberace is casting that lives up to the hype. He not only embraces the most eccentric corners of the script, but he also channels Liberace’s sinister ability to manipulate. At the very end during his goodbye performance in Scott’s imagination, he even finds a way to be endearing.

Behind the Candleabra is possibly the most entertaining role Matt Damon has had. To go back to dull biopics, Matt Damon recently starred in Ford v Ferrari, typical of the kind of thing you associate Matt Damon with: dull films you can safely watch with your parents. This is the rare step outside his comfort zone. The film works so well it never makes you question why a 42-year old actor is playing someone who first met Liberace when he was 18.

Dan Akroyd’s performance as Liberace’s seedy manager is the most memorable thing he’s done since the ’80s. Rob Lowe steals every scene he’s in. Scott Bakula, Paul Reiser, and certified Hollywood royalty Debbie Reynolds are also featured in the cast of never-ending names. But my “don’t sleep on this” performance is Cheyenne Jackson as the boyfriend Liberace is phasing out to be replaced by Scott. The way he aggressively eats while realizing his time is up is so simple and effective. The cast overall is one of those monumental gatherings you imagined stopped when the studio system went belly up.

Behind the Candelabra is one of the more extreme accounts of a celebrity grooming a spouse to cater to their every need. The first time Liberace meets Scott Thorson he says “ah, lost babe in the woods.” During their first night alone, Liberace recognizes Scott is someone looking for a sense of family after not being in contact with his birth parents. While having adopted parents, he still appears like an orphan looking for some place to call his own. Both men were born in Wisconsin, and it’s something Liberace mentions to build a feeling of familiarity.

Along the way, there are cars and houses Scott assumes to be in his name and a spot in the will, but once Liberace grows bored of him, it all disappears, and he walks away with a meager composition check. $75,000 might seem like a lot, but when a celebrity makes you get plastic surgery to look exactly like him while getting you hooked on the same drugs that killed Judy Garland, a bigger check might help soak up the wounds.

Behind the Candelabra is a faithful adaptation of a tell-all similar in tone to Mommie Dearest that successfully avoids the way that book’s adaptation developed a reputation for being a “so bad it’s good” film. It’s a testament to the way this film effectively balances tone. It knows exactly when to embrace camp and it knows when to be serious. It’s one of the most successful combinations of quality filmmaking and a good time.

If you’re in the mood for a double feature that feels like the sleaziest, steamiest Hedda Hopper column, these are the two perfect choices for such an evening. While exploring the more taboo and secretive corners of famous people, Auto Focus and Behind the Candleabra demonstrate how a biopic is done correctly. Nobody wants the dull, safe, and friendly Reader’s Digest story. All we want are the seedier tales that were never supposed to see the light of day. ★