“And it’s stupid when they say, ‘You only use your body. You are an object of men.’ No, I’m the subject. I’m not an object.” – Sabrina Salerno, Italian singer and showgirl, 1988

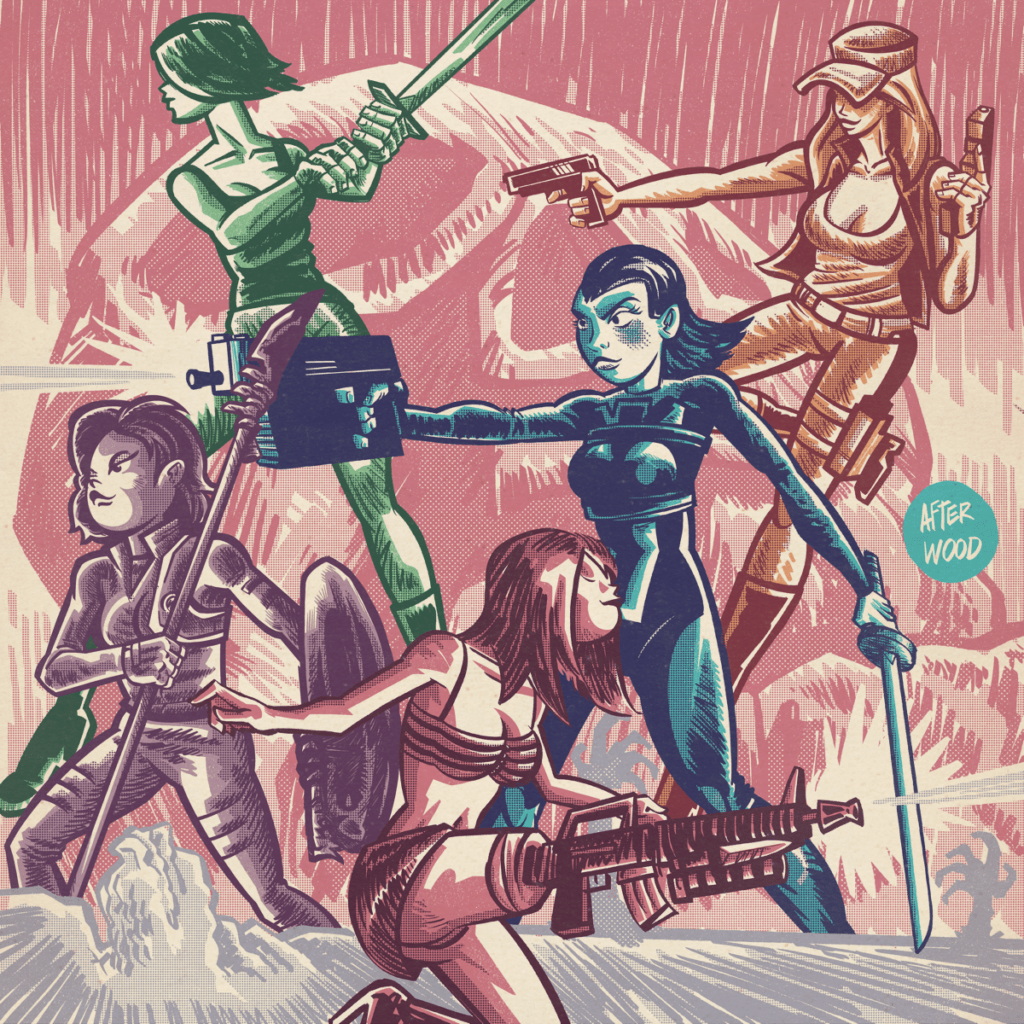

A hard-bodied heroine fights to protect a boy who may hold the key to saving humanity from a vampiric plague, the entire time with her midriff fully on display. A tenacious team leader sporting a tightly fitted tank top infiltrates a post-apocalyptic quarantine zone in search of a cure for a viral outbreak. A scientifically modified rogue heroine in a slinky dress and chunky boots fights alongside the security team of the evil bioengineering corporation who controls her to take the company down. A shrewd expedition leader in a form-fitting snowsuit sees her team killed and later joins forces with a monstrous alien to fight off a common enemy. A group of athletic adventure-seeking women trapped in a cave are forced to face off against genetically mutated humanoids. A feisty cat-suit clad vampire takes a stand against a centuries-long monster blood feud. All these descriptions come via a supposed mindless dead zone of horror: the extravagant era of the hyper-sexualized female-led action/horror movie, with its heyday at the start of the new millennium.

The decade 2000-2009 is one horror fans may like to forget. With the explosion of digital cinema and filmmaking becoming so easy that anyone with a Mini DV could do it, fans were bombarded with a slew of films ranging from not-so-great to mediocre to outright terrible by way of cable channels, direct-to-video outlets, and special on demand television options. (Shall we pour one out for FEARnet?) With so much sludge to erase from our collective memories, it’s no surprise that some of the really good films that came out of the same era are forgotten about too. Or, if not forgotten, written off in the same way as any number of not-so-serious film entries of the decade. And if the film is female-led, it seems as though not only are they written off, but actively scoffed at. Which may have everything to do with our perceptions of the deific entity that is Women In Horror.

Enough has been written about Women In Horror (WIH) that we need not get into the minutiae of the topic. But the progression of WIH from helpless victim to strong female lead is indeed a feat in itself, and what exactly it is that makes women strong in each scenario is up for debate. As B-movies and genre pictures advanced over the decades we see a change from one-dimensional characters to women of great complexity, starting with the Girl Gang films of the 1960s and ending up here with whatever you want to call the stuff “elevated horror” is supposed to represent. The Girl Gang pictures, although not explicitly horror in the macabre sense, were highly subversive at the time, giving audiences a chance to see a version of a female who is outspoken and active, who isn’t afraid to act in violence, and who generally rejects any traditional patriarchal idea of how a woman should conduct herself. So basically, a woman who is given the so-called characteristics of a man. In the 1960s this is seen as radical and perhaps a bit scary to traditionalists in its outright rejection of heteronormative behavior, but by reducing the character to its binary opposite, unfortunately it links to its own version of sexism. She-Devils on Wheels (1968) and Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) are early examples of exploitation cinema in which the traditionally male characteristics given to these gangs of bad bitches turn the women into freakish, sexualized fantasy material, the spectacle of which, although fun, arguably doesn’t do much to combat the androcentric nature of artistic expression at the time. Fast forward to the 1970s and ‘80s when the portrayal of WIH is largely that of “slutty slasher victim” until we meet our more complex Ellen Ripleys and Sarah Connors, who despite also taking on those traditional male leadership characteristics, maintain a sense of specialized femininity through survival instincts and representations of motherhood. Going into the current era of horror filmmaking, though, the WIH we see on screen belong to a new breed of horror heroine: one who is plagued by trauma, emotional turmoil, baggage, daily stress, and the psychological ramifications of living in a world in which she never knows if anyone will believe her. It’s films like The Babadook (2014) and Hereditary (2018) that lead in this category of female characters that make us question whether or not vulnerability is actually strength. And where Ripley and Sarah Connor still had a variation of sex appeal, these new heroines…not so much. But, granted, with them that’s not the point.

But there is a decade of horror filmmaking that takes all these characteristics and delivers them to us in a messily-wrapped package. Imagine yourself in the year 2000, just having come off of the high brought to you by “independent” cinema in the 1990s, where even WIH are know-it-all Gen-Xers waiting to be killed by the likes of Ghostface, or a snarky coven of teenage witches looking for power and revenge, or even Renee Zellwegger in a Texas Chainsaw situation for some reason. These things are relatively cool actually, but perhaps as the millennium came to an end you were itching for a new dynamic. You wanted your WIH to be smart and snide, and sexy and able to kick some serious ass. You wanted superheroines in monster’s clothes, dark action stars who provided both safety and an underlying sense of unpredictability. You wanted WIH who were exciting.

Post-1990s, that craving for excitement gave way to more highly sexualized and fantasy-based female protags. Thanks to Scream, mainstream horror in the mid-to-late ‘90s was more grounded in reality than it had been in previous decades. Teenagers saw themselves on the screen by way of characters who looked and talked like them, caring more about pop culture than that week’s football game, and showing more emotions than just “it’s time to party!” Plus, for maybe the first time, the adults in their stories took them seriously. Weird. But even as the Scream clones kept rolling out, the new millennium ushered in a different, more fantastic type of horror film. Call it male fantasy if you wish, but films of this period introduced a type of power female warrior that harkened back to the fantasy films of the 1980s (Red Sonja [1985], Sheena [1984]), but this time around more care was put into how the lady warriors were presented. If sexualization is basing a person’s value only on sexual appeal while ignoring other characteristics, the argument against the female-led action/horror movies falls flat. First, we have to assume that portraying characters as sexy is negative in order to make the argument stick. Second, we have to assume that these characters have no other value than being sexy. And those two assumptions are backed up by another one; objectification theory assumes that exposure to sexually objectified women in the media impacts women’s thoughts and feelings about themselves, and more specifically their bodies. But, if women are looking to be inspired by a fantasy heroine, these sexy and skilled monster hunters, justice seekers, and survivors transcend negative stigmas of objectification and become highly influential motivators.

The 2000s brought us three types of WIH action star: the Lone Heroine, the Team Leader, and the Team Player.

LONE HEROINE

The lone heroine usually has a vendetta. She’s often an allegiant soldier fighting for some kind of evil organization, like a megacorporation whose shareholders relish in keeping the world weak or ill, or a demonic patriarchal secret society whose ancestry goes back to ancient times. In Ultraviolet (2006) the titular heroine played by Milla Jovovich is tasked with protecting the bioengineering corporation that accidentally leaked a virus that turns people into pseudo-vampires against the last remaining humans who not only want their world back, but want justice. She is a hunter for the control-hungry world government, and she’s been assigned to infiltrate the hideout of a group of freedom fighters who are secretly housing a superweapon that could take the whole operation down. The weapon turns out to be a nine-year old boy who is a carrier of a virus that is very dangerous to the vampiric villains. In the end, faced with learning of the corruption inside the hypocritical corporation, Violet is overcome by sentimentality and flips her directive to save the boy and humankind in general. Underworld (2003) and its sequels are similarly driven by the heroine essentially being red-pilled into fighting the system she was brought up in: after years of being told one story by her father figure, vampire Selene (Kate Beckinsale) finds out the truth about the slaughter of her family at the hands of that same vampire himself. He killed her family and only spared her because she reminded him of his daughter (whom he also killed by condemning to death for betrayal). Both of these stories are about a person turning away from a malevolent ideology to gain their independence and sense of self. If we talk about empowerment, the Lone Heroine is the self-empowered precursor to our other categories of Team Leader and Team Player, because let’s face it, you can’t help others unless you first help yourself.

TEAM LEADER

The team leader is someone who gets the job done. She’s experienced and not only flourishes in specialized expertise, but knows how to motivate her teammates to succeed. Doomsday (2008) is a horror film that almost has everything: a viral outbreak, an apocalyptic quarantine zone, cannibals, corrupt government officials, cult leaders, a weird section that looks like medieval times, and a Mad Max-style road chase. Rhona Mitra is Eden Sinclaire, the strong and sexy heroine and leader of an elite government squad tasked with bringing civilians with viral immunity back into the free zone to find a cure. This one also falls into the rejecting false ideology via some form of enlightenment category with a redemptive arc, however Eden seems too detached to care that much ~ which makes sense for a character said to have been inspired by Snake Plissken. It may come as a surprise that Alien vs. Predator (2004) is decidedly feminine; that’s not to say that any part of this story of humans battling two different types of dangerous extraterrestrials is dainty. What heroine Alexa (Sanaa Lathan) possesses throughout the story is a keen sense of responsibility and caretaking toward her teammates, warning them several times to not act impulsively during their underground expedition. She also carries guilt from not being able to save her father from passing away from having developed a blood clot while descending the peak of a mountain they had just climbed together, so safety is her top priority. It could also be a feminine quality that she smartly decides to team up with one of her opponents (the Predator) to defeat a common enemy (the Xenomorph), rather than stoop to mindless barbarism. However, by the end, Alexa’s transformation from smart and sassy caretaker to sexy warrior babe may send up tribal exoticism red flags, but that’s just the kind of playing around with archetypes that leads us to fantastic future franchise entries like Prey (2022).

The most fruitful franchise of the 2000s in this female-led action/horrorsphere has to be Resident Evil, with the first entry hitting cinemas in 2002. Milla Jovovich stars as Alice, the virtually amnesiac protag charged with discovering not only her own identity and purpose but unveiling the dark truth of her employer’s motives. Alice wakes up alone, naked, in the shower of a mansion that seems familiar, but she looks for clues to help her figure out what’s going on. She’s joined by a security team, of which she is apparently the head, and they infiltrate the Umbrella Corporation’s underground headquarters to try to take control of a hostile situation. From there, of course, it gets very bitey and brains-eatey. Alice’s character grows more complex as the franchise goes along, with her subtly inquisitive nature in the series’ opening setting the stage for what her character will become.

Resident Evil gets some grief for being over-the-top and action-movie dumb, and for fetishizing its star, but aside from that the series continually offers an honest representation of women. Character archetypes in the first movie are exemplified by a gritty performance from Michelle Rodriguez, who is the bitch of the group, the one we might say is given typically male characteristics. As mentioned before, Jovovich plays her role as “the strong silent type” for a lot of the first film, but it’s clear she’s really taking in her surroundings to figure out the best plan for their situation. She is smart and quick on her feet. By the end of the first film and on into the franchise, Alice has fully taken charge, but another strong woman in a leadership role is introduced, Ali Larter’s Claire Redfield. This is where Resident Evil excels as a true feminist franchise: female trust bonds and friendship win out over any pettiness. Larter even points this out in an interview promoting Resident Evil: The Final Chapter in 2017 by saying, “It’s typical to see men in both of these roles. Here we are, three movies later together, [and] you see them build each other up. You don’t see the cat-fight, you don’t see us fall into those traps you often see in movies. You also rarely see two women leading a movie and doing that. There’s no question to me that [it has] that kind of feminist point of view on it.” So clearly, there’s much more going on here than simple sexualization.

TEAM PLAYER

There are a few films that fall into the “Team Player” category; these are the films in which our heroines are fighting evil amongst a larger group dynamic, regardless of leadership status. A lesser known film from this era is the French-language Bloody Mallory (2002), which very much has the feel of American television’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer in both “Scooby Gang” story beats and special effects execution. (The supporting gang here is made up of a male gumshoe, a drag queen, and a mute pre-teen girl whose voice is only telepathic. Say what you will about representation.) Mallory (Olivia Bonamy) leads a government-funded strike force dedicated to fighting the supernatural; her flaming red hair, revealing uniform, and bitchy attitude may not be the most professional, but they play to the fantasies of a certain type of anime/manga-loving audience member for sure. Planet Terror (2007) crosses a huge line into pure exploitation and is unapologetic about it. As the tradition of exploitation filmmaking has been largely androcentric, Planet Terror, with its focus on strip clubs, gross-out horror, big guns, and bbq, is no exception. The women are shown as conniving, vengeful, sarcastic, and wildly insane. The two main female protags are Cherry Darling (Rose McGowan) and Dr. Dakota Block (Marley Shelton) who are both having the worst day of their lives. It is surprising to some, perhaps, that these two characters who are highly sexualized in their own distinct ways (as an anesthesiologist, Dakota wields power over men with her set of needles ~ not to mention is caught up in a secret lesbian affair; Cherry is a former exotic dancer who spends the entire second half of the picture with a machine gun peg leg) remain so well cultivated in this movie. But that is again the object turning into the subject, as these characters possess way more value than just their sexualities. Hell, by the end of it, after the conclusion of a bittersweet love story, Cherry becomes the loving mother-figure of a group of cult-like friends and followers, expected to lead the survivors into the next era of civilization.

★★★

Exploitation and empowerment have a long history that plays out as if the concepts themselves were quarreling lovers. Exploitation is making a victim out of a person for personal gain, and the exploitation films of past decades are referred to in that way not only because of the subject matter of the films themselves but also the institution of filmmaking used to create them. Film savvy feminists will often give these exploitation and Girl Gang-like films a pass because of the utopian potential of nostalgia. Escapism and aesthetics create an idealized vision of the past, projecting the potentialities of female empowerment rather than documenting it. If we consider the female-led action/horror movies in the same way, we can detach ourselves from the reality of objectification and simply just enjoy something for what it is. Roger Corman once said that filmmaking is a corrupted art because films are a compromise of business and art. In the same way, we often negotiate with our ideologies in order to have a good time with something. Exploitation and genre films especially fall into this practice; whether it’s a Christian ideology or a feminist ideology or something else entirely, we compromise in order to enjoy them.

Insisting that such objectification and hyper-sexualization is empowering to all women is indeed without recourse, but insisting that the objectification of these WIH heroes produces only negative results is also particularly naive. It’s true that what we get with the male gaze on the most base level is a want for reproduction: in these action/horror movies, it’s the stomach showing and the “V” lines at the hips that all insinuate the womb. These physical characteristics are considered a kind of beauty standard, but beauty doesn’t necessarily have to mean sex, does it? A recent wave of backlash to the purported objectification of women in media has led to video game avatars for women becoming more diverse in body type, size, and facial characteristics (read: girls in some video games are now fat and ugly). What may seem like a win for feminism and objectification theory has also led to more backlash in its own right: turns out some of us don’t exactly care about being totally represented. As it is, sexualized video game avatars and action movie characters seem to build on our self-perceptions rather than diminish them. In terms of virtual reality, this is called the Proteus effect; we draw conclusions on ourselves based on our virtual characters. Whereas men typically see themselves as the character (“I am Batman”), women see themselves in the character (“Wonder Woman is me”). So, since Alice is smart, sexy, and adept, they are too.

Sucker Punch (2011) doesn’t fit within this decade, but is mentioned for its place in the progression of the female-led action/horror genre. A young woman is institutionalized at a hospital for the mentally insane against her will, and faces lobotomization if she doesn’t escape in time. The film jumps between fantasy and reality as the protag and her friends gather items they need to break out. Feminists don’t really like this movie, and one can understand maybe why they wouldn’t, but mostly it seems they have a vendetta against director Zack Snyder for being a dude. But, Lord knows he tried. Snyder has said about the stereotypical sexual fantasy characterizations in the film, “…my hope was that they would take those things back, just like my girls hopefully get confidence, they get strength through each other, that those become power icons. They start out as cliches of feminine sexuality as made physical by what culture creates. I think that part of it was really specific, whether it’s French maid or nurse or Joan of Arc to a lesser extent, or schoolgirl. Our hope is we were able to modify them and turn them into these power icons, where they can fight back at the actual cliches that they represent. So hopefully by the end the girls are empowered by their sexuality and not exploited.” Artist intent can always be argued as relevant or irrelevant, but to give Snyder the benefit of the doubt, the message here is that in order to fight against a stereotype, sometimes you have to embrace it. Take the stereotype and own it. Emily Browning, the actress who stars as team player Babydoll, furthers this idea: “It was extremely empowering to be able to embrace both sides: the sexiness and the strength. That’s something I think is really cool to see, that females don’t need to be placed in these boxes where you’re either sexy or you’re strong, you’re sensitive or you’re tough. That’s kind of ridiculous.” That the film flips back and forth between fantasy and reality within the mind of its main protag also solidifies the argument that women want their own avatars to be sexy, powerful, and in control.

As far as fantasy, Sucker Punch is the culmination of a decade’s worth of hyper-sexualized female action/horror films. But looking for a more grounded approach, we turn to 2005’s The Descent. Well, as grounded as a cult creature feature can be. The Descent is about a group of friends who are reuniting after a year to go on an adventure together, and it defies stereotypes. The women are going caving, and after an impulsive misdeed by a team member, they become lost and trapped underground amidst a flux of mutated humanoid monsters. What makes this film speak so much truth is that the women do panic and make rash emotionally based decisions which, in due time, exponentially worsens their situation, but they also exhibit a bravery and tenacity that helps them cut through any cattiness or instabilities the group dynamic might bring forth. These women are sex symbols not just because they are athletic and attractive, but because they command the audience’s respect. This is women in control; this is the object becoming the subject.

Feminists may argue that the change we see in WIH from the 2000s-era to now offers a more complex view of women as both characters and people, and therefore is more ideal and superior to their perceptions of flat sexualizations endured by female protags in that decade. In some ways that’s true, as women are more in the forefront in action and horror movies than they seemingly ever have been. But, “more” might not necessarily mean “better.” Today’s female protags are supposed to be stronger, but that strength seems to be a kind of compensation from the stigma attached to previous WIH. Women are now most often required to “win” no matter how they are portrayed or what actual capabilities they may have, and they are unrealistically able to destroy anything that comes their way almost effortlessly. Birds of Prey (2020) is an egregious example; during the Amusement Mile fight scene it’s the non-superpowered, comparably small and petite women who take out the gargantuan henchmen, some of whom are actual ninjas, defeating them all in sometimes just a single blow. Watching the film, it’s as if the big dudes are playing nice and actively trying not to hurt the girls, again resulting in its own form of sexism. Of course, this scene is presented as ridiculous, going as far as telling a meta-joke about Harley having time to change into roller skates to signal to us not to take it seriously. And we don’t really, except for internalizing that this time it’s female-driven power fantasy instead of male sexual fantasy (still with room for fetishization, of course). But for a truly satisfying story, the more feminist taboo-style flaws the protags have, the better. Without those flaws, there’s no suspense, no stakes, no room for an arc, and no real room for discussion. The slew of modern characters have no struggle to “find themselves” or to achieve self-empowerment because they already are the most powerful. So, if you play by feminism’s rules for female power fantasy, you are missing out on a ton of excitement. And that loss is in favor of a mere so-called ethical motivation for narrative, which does hardly anything but indulge in feminist escapism. Promising Young Woman (2020) is a horror-revenge story that proposes an even worse outcome: WIH who are survivors only become strong by turning into monsters themselves. But the misguidedness of Promising Young Woman’s female protag doesn’t matter because even a misguided woman is more “right” than any man, so she still wins out in the end. We’ve established that escapism can be okay, and even inspirational when done with the correct motivations, but when the fantasies are presented as somehow attainable in the real world, that blurred line leads more toward a delusional state of mind.

What we can learn from the female-led action/horror movies of the 2000s is sexiness and strength are not mutually exclusive. The supposedly mindless films of the era, trashed by feminists and film scholars alike, actually provide the most empowering message: we shouldn’t limit ourselves. So many of these films are about women breaking away from their oppressors, taking control of their destinies, and becoming righteously dangerous heroines ~ and looking hot while doing it. The problem is that the opposition looks at these characters only as how they are made and who is presenting them; they are products ~ or currency ~ not independent beings who exist to inspire the imaginations of everyone. Not just the imaginations of their creators, and certainly not just of sexists. ★