The frontiers of media provide lawless opportunities for artists. Before the corporate-appointed sheriff rolls into town, utopias of artistic expression are possible. What those utopic dreams are and how long they last is an entirely other thing, but the bleeding edge is still the most fertile place to plant them. The ’70s are famous for grindhouse theaters and drive-ins opening up a huge space for low-budget offerings; in the ’80s era of mom-and-pop video stores, the VHS tape renewed this legacy with rubber monster results. But around 2010, a crossroads of two unique technological moments also reopened this portal beyond the profane shackles of the entertainment industry. Digital, high-res cameras were now affordable to almost anyone, and streaming platforms like Netflix, just getting off the ground, were desperate for content. Unknown filmmakers without much backing, if any at all, could make a movie and get it into everyone’s homes. For some, this was the utopian moment to build an entire career. For others, it was the paradise of no censorship. The moment was even more fleeting than an entire decade could encompass, but it was a pivot point that grew into the booming genre scene of the 2020s.

The ’90s ended with a sudden middle finger to the highly polished, celeb-driven horror vehicles of its time. The Blair Witch Project (1999) was raw technically and used urban myth-building and viral internet tactics as promotions. These ideas wouldn’t directly shape the ’00s, but by the ’10s this approach was everything. Between an additional boost in this direction from Paranormal Activity (2007) and the societal expectation that a home video camera would produce fairly high-res footage, slews of found footage films began flooding digital distribution (REC [2007], Cloverfield [2008], Lake Mungo [2008]). One that made bigger waves than most was Grave Encounters (2011). Much like The Blair Witch Project, the narrative thrust is centered around a sort of In The Mouth of Madness (1994) unreliability of both time and space for the characters. Rather than being lost in a forest, they are hopelessly trapped in an abandoned mental asylum. Unlike The Blair Witch Project, the pace is as peppy as the best of ’80s DTV, with constant jump scares and cartoonish characters that the audience is content seeing sent to their deaths. The popularity of the film quickly led to a sequel that feels like another nod to the ’90s witch-christ at whose altar they worship. In Grave Encounters 2 (2012), a group of college filmmakers becomes convinced that the first film is a work of non-fiction and go in search of proving this belief on camera. They of course all perish. It is a sort of “let’s create our own urban legends” approach that is commonplace since Creepypasta has reached the mainstream. Grave Encounters may wear its influences on its chest, but it is also a part of an evolution forward.

The digital crossroads moment that built the most personal utopia was Mike Flanagan’s Absentia (2011). Feeling more homespun than others of the time, Flanagan’s artistic mastery allowed him to create an emotionally powerful story out of very little: Absentia is essentially crafted from just a few talented actors, an apartment, a nearby pedestrian tunnel, and just a kiss of CGI. This type of small, intimate horror wasn’t common to get buzz in the years or even decades leading up to it, but thanks to that hunger streaming services had for content at the time, this film built hype fast, launching what is now one of the biggest careers in contemporary horror. Eventually, Flanagan’s run of successes allowed him to return truly to this sort of melodrama, albeit with a much bigger budget, and make his opus The Haunting of Hill House (2018). Now with that, The Haunting of Bly Manor (2020), and Midnight Mass (2021), Flanagan is best known for the type of work he started with. There is even a Universal Horror Nights maze for The Haunting of Hill House ~ a wild place to end up given that Flanagan’s artistry is more about soap operas than monsters with chainsaws. For Flanagan, his 2010 digital utopia was personal not only in that it was just a good way to launch his own career, but also because it helped popularize a delicate sort of horror that continued to evolve through poetic works by other directors like The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015), A Dark Song (2016), and The Witch in the Window (2018).

Andy Milton, who would go on to direct The Witch in the Window, first struck gold at the digital crossroads, but with a slightly less delicate film. YellowBrickRoad (2010), co-directed with Jesse Holland, straddles the line of both a slow burn like Absentia and the trapped beyond time and space insanity of Grave Encounters. There are a few wisps of found footage, but YellowBrickRoad primarily has an omniscient camera. Much like The Blair Witch Project, it is about a group of people setting out to document a sort of rural legend. In this case, a mysterious and lost road that an entire town all decided to walk down one day and never returned. While not quite as energized as Grave Encounters, it shares that sort of Creepypasta vibe of a lot of wacky elements coming together, and it has a very violent streak going through it. It also has one of the boldest sound design moments of any horror film, regardless of the decade. For much of the film, the characters are plagued by ’40s music, very loudly coming from any and all and no direction at once. In a surprisingly long scene, this audio nightmare turns into pure harsh noise. It is a sort of brutal soundtracking unlike either the orchestral or synth-based sounds most common to horror. This grittier approach would start to be more accepted as 2020 approached, but YellowBrickRoad still stands out as having one of the boldest uses of the technique. A blessing of not being under expectations and just getting to make wild art and going directly into living rooms with it.

This “let artists do what they want” sort of Christian-socialist utopian filmmaking is no better manifested by the return of anthology horror at that time. The ABC’s of Death (2012) not only gave an opportunity to 26 directors to share their visions, but it also allowed them to do so in a completely uncompromised fashion. A fairly diverse assembly of artists from all over the world, working often in their native languages, the film is lovingly all over the map when it comes to style. While violence, like in YellowBrickRoad, is typical of these pieces, there are a few so taboo-breaking that it feels shocking they were able to get made. Simon Rumley’s “P is for Pressure’ would be simply crass in its depiction of kitten stomping if it were not for how much sympathy is rightfully given to the mother and her children who benefit from it. This isn’t a clear-cut tragedy. It is a wise portrayal of the ethical compromises this horrible world asks parents to make. “L is for Libido,” by Timo Tjahjanto, goes much further though with taboo-crossing, and doesn’t tip its cards as much for the rational ~ if it has any at all. There is so little information given in terms of what the piece could be a real-life analogy for, viewers are left to decide for themselves if it is just an exercise in sensationalism or a metaphorical examination for our actual lives. Regardless, it is a brutally cynical depiction of human nature, exceptionally well crafted, making it impossible to forget.

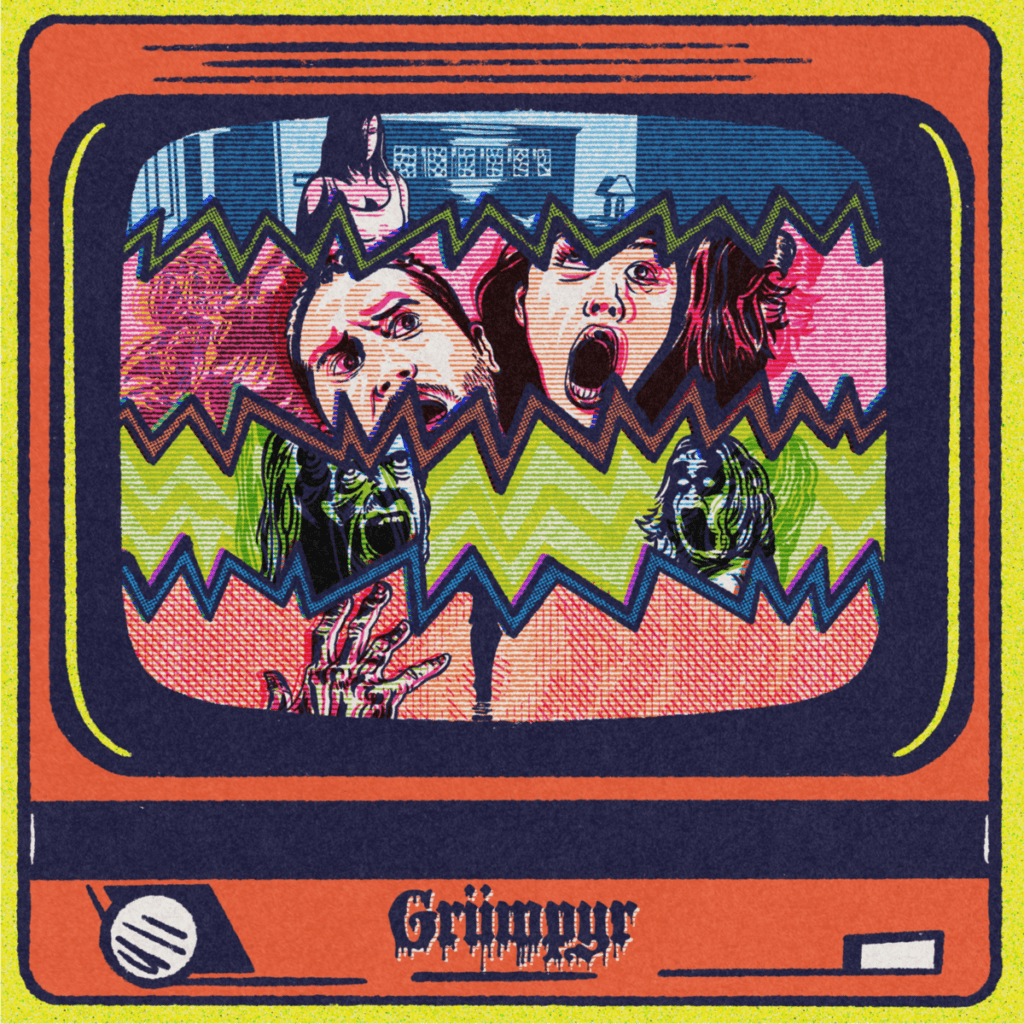

V/H/S, from the same year, is a different beast though. Like Grave Encounters, it uses the democratizing medium of found footage but uniformly is violent without any sort of “but it also makes you think” moments. In these shorts, all the men are bastards and all the women are bitches. Despite emerging at this utopian era in genre film, the fictional content here is absolute dystopia. Between horrifying content, visuals with as much distortion as YellowBrickRoad‘s audio, and thick, viscous layers of toxicity, there seems to be only one clear message in V/H/S: this world is garbage. A funny contradiction with the fact that the very success of the movie proves there is at least a little hope otherwise.

2012 didn’t stop with this thrust towards the grim here though. Smiley is equally vile as V/H/S. It integrates found footage (in this case, web videos) and omniscient camera like YellowBrickRoad, and dives deep into the Creepypasta legend-building. Most importantly, it combines all these elements in order to make a harsh critique of internet culture. The primary characters are 4chan users who bully in real life as much as they do online. They use their privilege as young people with safe, spoiled, well-educated lives to make sophist arguments justifying having no ethics: justifications starting at online child pornography and ending at real-life murder. The entire film is all the more unsettling thanks to very non-traditional, almost amateurish cinematography. The digital medium is so under-lit that it feels like a home movie, the framing is often confusing and the editing frequently feels like shots are missing ~ all elements common to quickly made youtube movies. Smiley itself has the temperature and tone of the type of internet content it is about. A quick glance at the sort of viewer criticism Smiley has gotten helps prove the point the film is making. These negative “user reviews” on sites like Letterboxd amount to “Oooo cringe. You think the internet is evil? What a deep point you have.” A film about the type of online bullying that led directly to Trump-era online politics is constantly bullied by people using the same zero-discourse tactics. Of all the films mentioned in this essay, Smiley continues to have the most to say about the current state of our world that still is negotiating what it means for our real lives to be experienced in virtual spaces. This isn’t helped though by the fact that the primary way the film has been promoted is in bragging about how many views the trailer got. At the top of the Blu-Ray release is the text “Over 30 Million trailer views.” It is slapstick level tragedy that a movie reminding us to avoid mob mentality would market itself with an appeal to exactly that.

All of these films have overlapping tactics. Even Absentia, the classy film of the bunch, revels in the home-made feel of low-budget digital camera work and has a sort of Creepypasta troll-under-the-bridge legend at its core. The creators, though, all got away with bringing some startling and often game-changing ideas thanks to this crossroads of digital camera availability and Netflix’s desperation for content. For the most part, slicker versions of these ideas would get the more widely accepted credit for doing something new in horror just a few years later. That is the fate of the bleeding edge: true success often lies not in being the first to do something, but the second. The people who do things first pave the way; the people who do them second do it with cultural acceptance already there for them. On a technical side, it is also the bleeding edge who have the most limitations and have to make the mistakes others benefit from seeing how to avoid in advance. The bleeding edge has advantages beyond what comes after it, though. It has freshness and an untethered passion that can’t be intentionally recreated. It is wild. It is punk. And it is rare that a moment in art like this gets a viewership as large as it did. ★